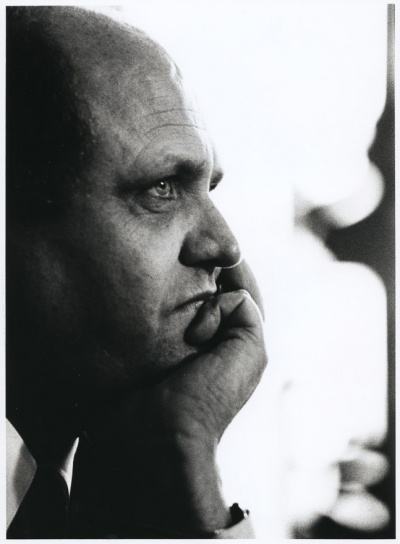

OBITUARY: Mike Moore, NZ's 'most promising Prime Minister'

Mike Moore would often describe himself as “New Zealand’s most promising Prime Minister.”

It was a reference to the number of promises he made during the 1990 and 1993 election campaigns, both of which he lost while playing an almost impossible political hand as if he held all the aces.

That was classic Moore: self-deprecating and memorably quotable – the Lamburger was one of his first contributions to the Kiwi lexicon. It also gave just a hint of the gigantic personal drive that took a shoeless boy from the Hokianga who never got past secondary school to leadership of his country and, later, the World Trade Organisation.

Indeed, Moore may go down in history as the Labour Party’s last working-class leader.

Before the 1990 election, Moore had been Prime Minister for a mere six weeks.

A tribal Labour politician to the core, Moore knew he was accepting the hospital pass of the century by taking over from Geoffrey Palmer in the dying days of 1984-90 fourth Labour government, in which he served mainly as foreign and trade minister.

Palmer was a ponderous replacement for the witty and mercurial David Lange as that administration imploded under the contradictions of the Rogernomics revolution, which Moore had helped usher in as a member of the notorious 'fish and chip brigade' that propelled Lange to the Labour leadership in the first place and set the stage for Douglas's ascent to the finance ministry.

Moore said later he only replaced Palmer “to save the furniture,” but saw it as his duty to lead Labour, a party that was riven by the Rogernomics revolution, into an unwinnable election.

Nonetheless, he backed himself to connect with a critical minimum of traditional Labour voters and the new breed of Labour supporter who supported opening up the New Zealand economy.

This was a crucial distinction between Moore and both the left and right of the party.

While he railed at times – both publicly and privately – against the crash-through radicalism of Roger Douglas’s economic reforms, Moore was at heart an internationalist with a deep belief in free trade. By his own definition, he was “an extreme moderate” and saw those opposing free trade as doing no more than “promising a better yesterday”.

His press secretary during the 1993 election was former RNZ political reporter Paul Jackman, for whom a stump speech that Moore gave in 1990 outside the Onehunga Workingmens’ Club was a pivotal moment.

“He said his stance on foreign trade was derived from The Wobblies,” the colloquial name for an early 20th century American trade union movement, Jackman recalls.

“Trade unions are often protectionist by instinct, but the Wobblies were much more radical. They were serious left wingers and they weren’t interested in exporting unemployment.”

Here was a “man of the left” arguing not only that free trade would make New Zealand richer, but that it was fair to give workers everywhere the same opportunity to compete than to protect local jobs.

“It was so wild and enchanting and I thought it was great.”

Much about Moore was wild and enchanting, albeit occasionally baffling.

His unkindest critics called him ‘Mad Mike’ and said he was a guy who had 100 ideas a day, of which only one was any good.

Loyalists say 99 out of those 100 ideas were good. Picking the ones to implement was the real challenge.

His stream-of-consciousness style was a challenge for reporters, who often quietly ignored the rules of direct quotation to make sense of the thoughts that tumbled out when Moore was on a roll.

Typical of his brave brainwaves was the trade mission he led to Eastern Europe in early 1990. The Berlin Wall had just fallen and Moore wanted New Zealand traders and agricultural technology to get in early. He put 80 Kiwis on an air force plane for a wild fortnight romp behind what remained of the Iron Curtain.

The Warsaw correspondent for The Financial Times couldn’t get his head around why we were there and in Budapest, a translator struggled to interpret the emphatically delivered Moore-ism: “Rice, tapioca, BMWs!”

‘Moore Puzzles Hosts’ ran the headline on my ungracious report in the Christchurch Press. Despite such mockery, Moore remained unfailingly generous to me and other travelling New Zealanders, putting us up in his spare room in Geneva on trips to check on his greatest international appointment: director-general of the World Trade Organisation.

Won in a hard-fought battle that saw his term shared with the Thai deputy prime minister, Supachai Panitchpakdi, Moore delighted in detailing how his frugal campaign involved weeks in a cheap Geneva hostel “washing out my own socks and undies while my opponent turns up with a party of 20.”

Diplomats winced, but it was the Moore that ordinary Kiwis loved.

First elected to Parliament in the landslide Labour victory of 1972 to the Auckland seat of Eden, Moore was barely 23 years old, assisted by tyros like Phil Goff.

He lost the seat in 1975 and moved south to win the Christchurch seat of Papanui in 1978, representing the same constituency until his departure from Parliament in 1999.

Moore felt the 1993 election loss deeply. All but abandoned by much of the Labour hierarchy, he relied on a band of acolytes from the right of the party, dubbed “the Beagle Boys”, to deliver pamphlets and erect hoardings, often in the dead of night.

In a sometimes bitter valedictory speech before leaving Parliament for the WTO post in 1999, Moore said they had “worked 18 hours a day, and were criticised by people who could not come to work for 8 hours a day.”

With the party splitting rancorously along cultural as well as economic policy lines, Moore was swiftly replaced as leader by Helen Clark, who took another six years to lead Labour to victory, while to the right and left the Act and Alliance parties were in their infancy, the practical fallout of Labour’s political agonies.

Moore expressed regret and bafflement that women in the Labour Party had failed to stick up for his wife, former children’s TV presenter Yvonne Moore, when she was subjected to personal attacks from within the party.

“I was always bewildered as to why you suffered so much abuse from some who should have known better, and why some of the sisters did not reach out to help you. I am still confused about that,” he said.

Once in Geneva, Moore was instrumental in the historic act of bringing China into the global trading body and in 2010, the National Party-led government of John Key made him ambassador to the United States.

Moore’s stint there was cut short after heart trouble and a stroke, in 2015, forced his return to New Zealand.

To many, Moore was a flawed genius; to others, a traitor to the Labour cause despite his working class roots and his moderating influence on the Douglas reforms. Moore himself was desperately disappointed not to win in 1993, when he came so close that on election night, National Party leader Jim Bolger uttered the immortal line: “Bugger the pollsters.”

Jackman suggests a legacy that few have recognised.

“I think of Mike Moore politically as a hero because he stopped the far-right adventure in New Zealand,” he says.

Had the National Party won by a comfortable margin in 1993, it is far less likely that Bolger would have dispensed with Ruth Richardson’s services as finance minister.

Moore’s was a centrist vision, one that embraced “the real battlers, who want to own their own homes, who, in the main, look after their kids, run the netball teams, and wash other people's children's football jerseys.

"They are the cream. They do not want a government to tell them what to eat, who to meet, and how to greet. They simply seek the gift of opportunity, and that their children have a better life than themselves. As Norman Kirk, who represented Kaiapoi as mayor, said: ``They don't ask much: someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work, and something to hope for.'”

Mike Moore died overnight last night. He was 71 years old.

Born: 1949, Whakatane.

Raised in Moerewa, Northland.

Education: Bay of Islands College, Dilworth School (left school at 14)

Entered Parliament: 1972, Eden electorate, defeated 1975

Returned to Parliament: 1978, Papanui electorate (held for 21 years, with name changes to Christchurch North and Waimakariri)

Prime Minister: 4 Sept. 1990 - 1 Dec. 1990

Minister of External Relations and Trade: 1988-90

Minister of Overseas Trade and Marketing: 1984-90

Minister of Tourism, Sport and Recreation: 1984-87

Minister for The America's Cup: 1988-90

Leader of the Labour Party: November 1990 - December 1993, replaced by Helen Clark

Director-General, WTO: September 1999 - September 2002

Ambassador to US: 2010-2015

Died Feb. 2 2020

Survived by his wife, Yvonne. The couple had no children.

Comments