OPINION: Media merger phoenix has another crack at rising

Having failed with the competition regulator, and then in the courts, the NZME/Stuff merger of news publishers is being revived with a scheme that would effectively make politicians responsible for deciding which bits of legacy media are allowed to close.

In a statement to the NZX after Stuff broke a story on the subject this afternoon, NZME confirmed it has been talking to the government about such a "Kiwishare" arrangement that would allow it to buy its financially challenged competitor, Stuff.

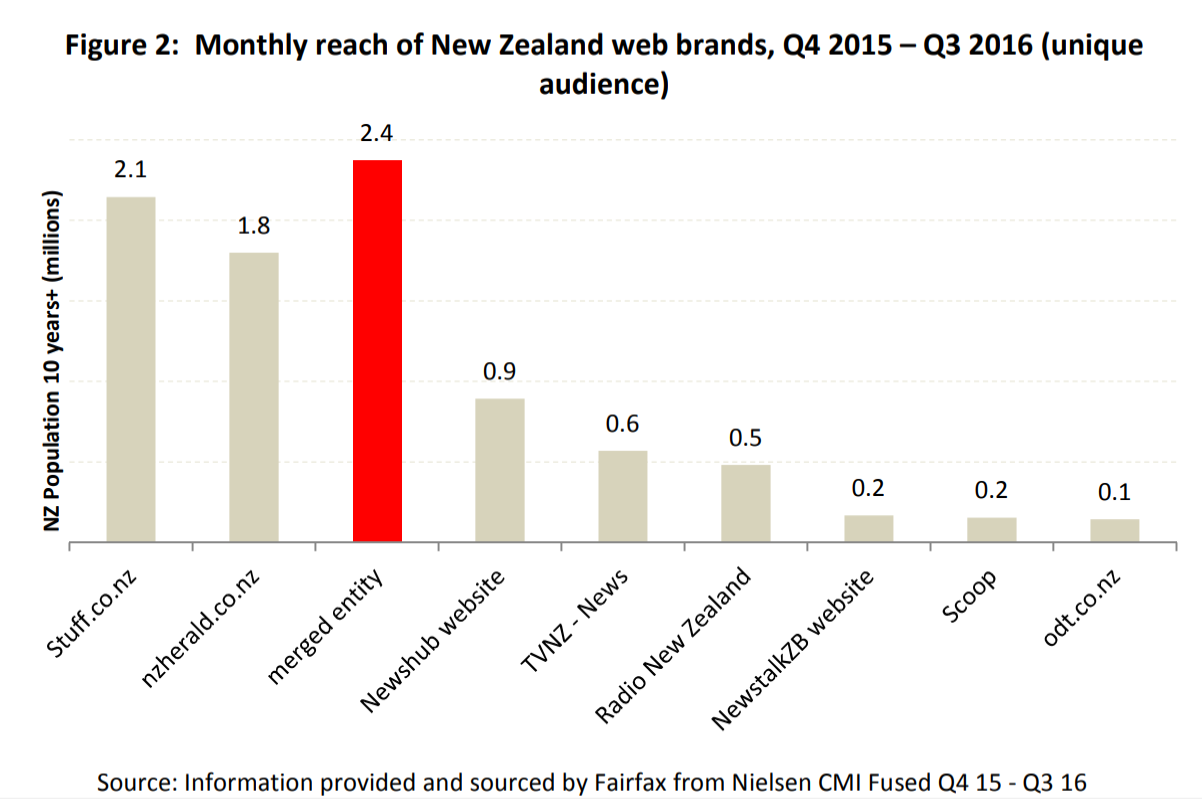

The Kiwishare would, apparently, require the merged entity to abide by certain public interest tests, for example: how much news it published, how it ensured that news was spread around the regions, or preserving a certain level of the 'media plurality' - a range of journalistic voices and opinion. The loss of plurality was the Commerce Commission's reason for rejecting the merger in 2016.

After losing all the way to the Court of Appeal last year, the would-be merger partners went back to the drawing board.

In the meantime, Australia's Nine Entertainment Corp bought Fairfax and tried fruitlessly to quit the Fairfax stable's Stuff assets earlier this year.

At some stage recently, things have got serious again between NZME and Stuff's post-Fairfax owners. The Kiwishare proposal is the outcome being dangled for ministers and regulators to consider now.

Yet just how the merged entity could guarantee that it would be able to maintain meaningful journalistic obligations through a Kiwishare and satisfy its shareholders must be debatable.

While the news publishers will argue the strengthened merged entity will be commercially viable, the reality is that revenues and profitability at both NZME and Stuff have been plummeting for a decade as advertising and news move out of print and onto the internet.

This is not a Telecom situation, where the Kiwishare obligation to provide free local calling was the price for privatisation of a company with a clear commercial future. Telecom, now Spark, chafed at that obligation, but it was a simple requirement, a bearable cost, and it's kept its word - at least for copper line calling, if not internet-based phone services.

Metricating a Kiwishare deal on standards and quantities of journalism feels much harder.

While the new merger proposal doesn't involve government funding to rescue private media companies - something the government won't countenance and has rejected for TV3 - it does involve ministers deciding whether the Kiwishare commitment is being met. How willing will they be to insist on non-commercial journalism targets if the merged company's fortunes continue to ebb?

That question is all the more relevant because the NZME/Stuff proposal coincides with the government's own work on merging state-owned Radio New Zealand and TVNZ, probably as an ad-free public interest broadcaster leveraging NZ on Air funding in new ways.

One way for a minister facing hard choices about commercially imperilled private sector news services would be to encourage that beefed-up state media company to do more of the kind of content-sharing arrangements that are growing like topsy between private news organisations and RNZ already.

But would that really create the vibrant media environment that all parties are concerned is being lost? Or might it become an avenue for a Crown-subsidised leg-up for private-sector media players who know that politicians will always prefer to see them propped up than preside over their failure.

An amalgamation of effort in this small market may well be the only route to survival against the Google and Facebook behemoths for legacy media players. The government may decide that is a worthwhile public interest goal. However, there's nothing to say much the same outcome wouldn't occur without a Kiwishare if the government just left the existing and new media players to sort out successful new commercial models for news production, which are finally beginning to emerge.

If the political incentives of the Kiwishare proposal drive to an increasingly centralised, monolithic public-private partnership between the big existing players, that will suit those players just fine.

But will it really create the plurality of voices and opinion the Commerce Commission and the courts said was so important in the first place?

Comments