This article has been republished. It was first published in October 2020.

Starlink, a subsidiary of Elon Musk’s SpaceX, is registered as an unlimited liability company in New Zealand but uncertainty surrounds its presence here despite public records showing three directors, including one who BusinessDesk spoke to exclusively.

Records show Starlink plans to offer a satellite internet service in addition to leasing antennas at a ground site near Invercargill to communicate with satellites.

BusinessDesk also found that Starlink’s three NZ trademark applications were rejected in January.

Starlink’s goal is to use low earth orbit satellites to bring reliable high-speed internet services to rural areas that lack decent fibre broadband or cellular network coverage. The satellites orbit at a height of around 500 kilometres, which gives them five to six years before they re-enter Earth’s atmosphere.

This means the company needs to plan to launch a vast number if it wants to provide international internet service over several years. On Oct. 19, Starlink deployed 60 satellites, bringing the total reported number launched to 835. The figure is planned to sit at 12,000, and in October 2019 SpaceX requested permission from the International Telecommunication Union to launch up to 30,000 more.

All local evidence points to SpaceX’s confidence in NZ’s place in the Starlink service, but it seems to have been a bumpy ride so far.

The man with the secret plan

Robin McNeill is space operations manager at Awarua satellite ground station, run by Great South, Southland’s regional development agency. He has a long career in engineering and telecoms and was made a Member of the NZ Order of Merit for services to conservation on the 2017 Queen’s Birthday honours list.

Awarua is one of four satellite ground stations that SpaceX wants to use for specific radio bands, according to a US Federal Communications Commission document. The other three locations are at Brewster, in the US state of Washington, Cordoba in Argentina, Tromsø in Norway. McNeill works with commercial companies who covet Awarua’s remote southern location for optimal satellite data communications.

He is also one of three registered directors of Starlink NZ. A non-disclosure agreement stopped him from discussing Starlink’s work directly.

The other two directors are US-based David Anderman, SpaceX general counsel and the former COO of Lucasfilm, and Lauren Dryer, a principal operations engineer who has been at SpaceX since 2006.

“We have a big green flat paddock at the bottom of the world with 100 gigabits per second fibre-optic, electricity, generators, backup and technicians,” said McNeill of the Awarua station’s appeal.

“It’s flat as a pancake. We can see right to the horizon and there are no people, so no radio interference, and no radio users compared to the rest of the world. It’s very easy to do frequency coordination.”

Image: Awarua ground station (Robin McNeill)

Image: Awarua ground station (Robin McNeill)Having a ground station at the South Pole would be optimal, McNeill said, but the complication of having long term staff in the hostile environment means Awarua is as close as a ground station can get to icy ideals. With satellites frequently set to orbit over both poles, it makes the location incredibly attractive for leasing land to set up antennas for commercial customers.

Meanwhile, satellites that provide communications services must transfer data between several points on the earth during their orbit with antennas set up at locations known as ground stations. It’s not necessary for all Starlink affiliate companies to have in-country ground stations, but NZ happens to be a country with a desirable location for one.

On Sept. 24, SpaceX applied for a license in Alaska to be an internet service provider. The document lists SpaceX’s alien affiliates, one of which was ‘TIBRO New Zealand’. TIBRO spells ‘orbit’ backwards, and the name was used for several affiliates in other countries.

On Oct. 2, NZ Companies Office records show a change of company name from TIBRO New Zealand to Starlink New Zealand. The presenter, David Quigg of Quigg Partners law firm in Wellington, where the subsidiary's NZ offices are listed, refused to comment.

A similar name change of Starlink’s Australian affiliate from the TIBRO name is also on the public record.

Red tape

NZ Intellectual Property Office records show SpaceX applied for three trademarks for use of the Starlink name in NZ in January. One application was for class 9 goods relating to commercial satellites, and the other two were for class 38 and class 42 services relating to satellite communication services.

BusinessDesk found through an Official Information Act request that all three were rejected in the same month due to similarities with trademarks held by Subaru since 2012 for its Subaru Starlink in-car technology system.

The applications reflect SpaceX’s desire to provide Starlink’s internet service in NZ using satellites launched from the US. The records show SpaceX can submit an objection response or make changes to the applications by Jan. 3, 2021 or the applications will be abandoned. The records did not reflect that the company has taken either action, but it still has over two months to do so.

SpaceX did not respond when asked for comment on any of its Starlink operations in NZ.

Future Starlink customers will need branded satellite dishes to receive service signal, which Musk has said will be ordered online. The programme is currently in beta testing according to a July report, which said a small number of US citizens have received dishes free of charge to test the service.

Designed to orbit near each other, the so-called constellations of satellites can sometimes be seen from earth in unnatural straight lines of light across the sky, a sight that upsets some local stargazers.

Starlink NZ’s existence as a company is notable because SpaceX does not need a registered NZ company to legally offer New Zealanders its internet service or build and lease antennas at Awarua.

According to MBIE, Starlink or any company could also ask Great South, or other ground stations, to hold the necessary radio spectrum management licences on its behalf, according to McNeill.

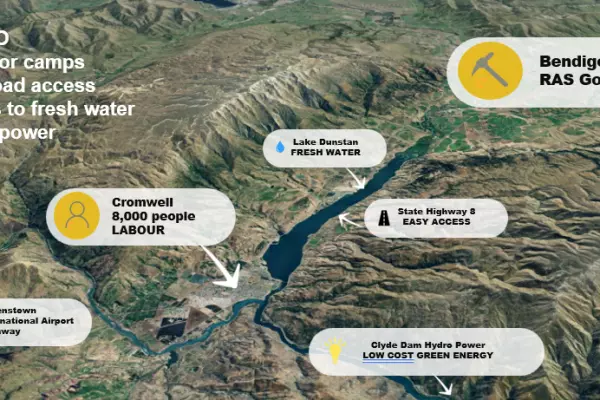

Radio spectrum management records also show multiple current spectrum licenses held by Starlink NZ for satellite communications and confirms additional internet gateway locations used by the company at Wellsford and Cromwell. MBIE said that licenses are not necessary for use of alternative ‘open’ radio frequencies.

But McNeill said that many companies prefer to hold the licenses themselves to have full control and be the party answerable to authorities, one possible reason for Starlink NZ’s existence. Given Starlink does not need to own land as it appears to be set to lease antennas on land at the Awaura site, the NZ company likely exists in order to own radio spectrum licences, or to employ people in NZ, or both.

Open space

Back at Awarua, McNeill said business is good.

“Business is booming for us. We install antennas where you don’t get change from a million dollars, and we’ve got the continual work of updating, replacing dodgy bits, putting servers in, and increasing capacity,” he said, noting that the pandemic hadn’t dented interest in services and that some projects could create permanent jobs in the area.

He also said that he was in negotiations for Awarua to support missions to Earth-Moon Lagrange point 1, a point in space where the earth and moon’s gravitational pulls cancel each other out, allowing spacecraft to stay in one spot to stably monitor the moon.

“By the end of this year we’ll be doing over a million dollars’ worth of weightless exports, with a good growth trajectory.”

With other weightless export industries like gaming suffering due to lack of government funding, the ongoing success of the ground station without such funding is encouraging.

“We’re doing OK without them to be honest,” he quipped. “We have relationships with various space agencies around the world since we’ve been working on Awarua since 2004. The space community’s pretty small so we know who to talk to.”

He’s evidently been talking to Starlink and said he has good relationships with Rocket Lab and San Francisco’s PlanetLabs. He believes satellite internet services are ultimately a good interim service, but that fibre networks are the long-term solution to NZ’s rural connectivity issues.

He suggests Starlink is another of Musk’s many sideshows distracting us all from the tech entrepreneur’s main ambition.

“His passion is getting to Mars. I don’t think he’s that interested in the internet,” McNeill said.

Mars may be the end goal, but it seems as though Musk is poised to take advantage of NZ’s useful geography to support Starlink globally, as well as offer its internet service here.

His colleagues might need to work on those trademarks.