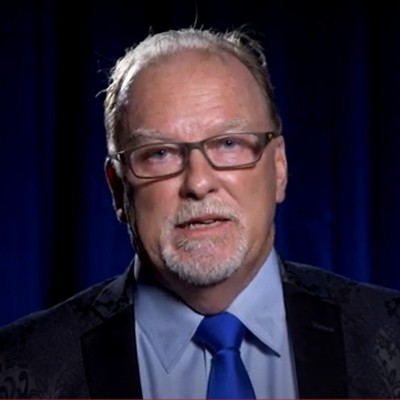

Shut everything down! That’s the unequivocal advice Wellington cybersecurity expert Bruce Armstrong has for people who find themselves suddenly frozen out of their computer at work.

When you are trying to contain a ransomware attack, stopping the spread of malware through your company’s network is everything, says Armstrong, founder of cybersecurity intelligence firm Darkscope.

Ransomware is a particularly cynical form of cybercrime that hackers first experimented with on home computer users, before perfecting their techniques and moving onto juicier targets – large businesses and government agencies.

A ransomware attack involves hackers infiltrating a computer with malicious software that locks it up, encrypting the data stored on its hard drive. Messages then arrive from the criminals demanding payment, usually in the form of the bitcoin cryptocurrency, to restore order.

As computers in medium-sized and large organisations are usually connected to each other via an IT network, the hackers’ aim is to get their software payload onto a company’s servers, where applications and data are hosted. The results can be crippling, as the Waikato District Health Board discovered in May when a sophisticated attack locked up hundreds of computer servers that run everything from staff email to clinical and diagnostic software programs.

The National Cyber Security Centre said in its annual report last month that of the 404 cybersecurity incidents it recorded against “nationally significant organisations” in New Zealand, three were classed as “highly significant”, the Waikato DHB attack among them. The only higher classification is “national emergency”.

Governments all over the world have been the subject of high-profile ransomware attacks this year. We hear less about the private-sector organisations that also fall victim.

“Recently, a sales manager at one of our clients clicked on a link in an email,” says Armstrong. “It locked up her computer.”

The company responded quickly, shutting down computers and isolating infected devices so that just a few servers were locked up. But business ground to a halt for a day. Sales and warehouse staff weren’t able to process orders.

“The servers had to be completely wiped, reformatted, and restored from data backups,” says Armstrong.

He estimates the loss of business over a 24-hour period, and costs associated with restoring the network and computers, would have amounted to tens of thousands of dollars.

The Ford Pinto test

This goes on every week as businesses face ever more sophisticated ransomware attacks and suffer the consequences of a lack of cybersecurity preparedness.

Despite the financial and reputational risks of falling victim to an attack, Armstrong says, a surprising number of businesses have a lax attitude to protecting themselves. Many executives, he says, are running a version of the “Ford Pinto test”.

In 1971, Ford rushed to market the Pinto, a compact car model it knew from preliminary crash tests had a high risk of bursting into flames in a collision. Ford was facing stiff competition from Volkswagen in the small-car market. It needed a sales winner and ignored the warning signs to launch the Pinto.

A series of fiery and fatal crashes revealed the extent of the problem, resulting in a massive recall of Pintos and delivering a stern lesson in business ethics to corporate America.

“Is it cheaper to ignore it and carry on, or to stop and address it?” Armstrong says. “That, unfortunately, is the business reality. Sometimes it’s cheaper to let the car catch on fire.”

Armstrong says New Zealand businesses also rely too heavily on software vendors, effectively trying to outsource their cybersecurity risk, when the real answer to deflecting attacks is as much about the culture of the organisation as it is about firewalls and security software. Cyber insurance is now a must-have investment to help cover the losses resulting from disruptive attacks.

Cyber security expert Bruce Armstrong. Photo: Supplied.

Cyber security expert Bruce Armstrong. Photo: Supplied.

The introduction of the new Privacy Act last December should have served as a wake-up call. It requires organisations that become aware of a data breach to report it to the Privacy Commissioner within 72 hours. Non-compliance is punishable by a fine of up to $10,000. Armstrong says that’s not enough of a deterrent to many businesses who would rather “ignore the problem and hope that it goes away”.

He recently alerted a New Zealand company to the fact that its data, including customer addresses, passwords and some financial information, had been released on the dark web. It turned out the company already knew of the breach.

“I said, ‘What are you doing about it?’ They, said, ‘We aren’t sure yet,” says Armstrong. The data had been available for at least three days.

Under the strict General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) introduced across Europe in 2019, that attitude could result in major penalties. British Airways paid a fine of 22.4 million euros ($37m) that year after users’ traffic was directed to a hacker’s own website, where personal data was stolen.

Italian mobile operator TIM was last year hit with a fine of 27.8 million euros ($45.9m) for lax security practices that led to data breaches. Under the GDPR, fines for mishandling data breaches can be issued for up to 10 million euros ($16.5m), or 2% of a company’s global revenue.

So far, 880 breaches have resulted in fines totalling 1.29 billion euros ($2.13 billion) being issued by EU nations, though the bulk of the penalties relate to improper use of customer data rather than security breaches resulting from hacking attacks. Amazon was fined 746 million euros ($1.23b) after Luxembourg’s data watchdog found that its advertising-targeting system was operating without proper consent.

“GDPR has real teeth,” says Armstrong.

California has followed Europe’s lead with a privacy law under which the state can impose a fine of US$750 for every individual whose information is compromised. “If you have one million customers, that could be a $750 million fine,” Armstrong points out.

Aussie’s ransomware crackdown

Across the Tasman, Australia has just beefed up its cybersecurity law, adding specific offences for ransomware attacks and making it mandatory for companies with annual revenue of A$10 million or more to inform the authorities when they’ve had a cyber-attack.

“Australia has the willpower to do it. We don’t yet,” says Armstrong.

Tougher laws here would both deter hackers and force businesses to be more proactive on the cybersecurity front.

Says Armstrong: “If we are hard to breach and hard to get money out of, we become less attractive than some hospital in the middle of America that has a big insurance policy and will pay out.”

Ransomware attacks first emerged nearly a decade ago. But the criminals’ techniques have evolved radically in recent years and the rise of cryptocurrencies has given them a way of receiving extortion payments anonymously without having to rely on bank accounts.

Mark Anderson, Microsoft Australia’s national security officer, says hackers have established a sophisticated global supply chain of tools and services. A basic ransomware kit can be purchased on the dark web for as little as US$66, with some suppliers waiving fees in return for taking a 30% cut of extorted payments.

It used to be that ransomware hackers would simply demand payment to unlock your data. Now they threaten to dump it on the web for everyone to see.

“Now, rather than just encrypting a user's or victims’ files and requesting a ransom in exchange for the decryption key, the attackers are also exfiltrating sensitive data before deploying the lock in ransomware,” Anderson said this month as he outlined the findings from Microsoft’s latest Digital Defence Report.

“If you disengage from the negotiation, the threat is that the actor will then release your sensitive information that they stole before they encrypted your environment.”

Microsoft’s Cyber Defense Operations Centre has detected a surge in ransomware attempts across its vast network – from around 50 million in mid-2018 to 100 million this year.

Nobody spared

Despite shadowy hacking groups that specialise in ransomware vowing to spare hospitals from attack during the covid pandemic, Anderson says healthcare providers still feature in the “top five sectors” targeted. With ageing and underfunded IT systems, they are just too attractive a target.

The findings of an inquiry into the Waikato DHB attack are still to be released. But experts like Armstrong agree that it was well planned and sophisticated.

“They played a long game,” says Armstrong. “Judging by the information they released onto the dark web, we reckon they were in the system for at least three months and up to six months. They had human-resources records, emails. They were accessing several walled gardens on the network.”

The ransom demanded is thought to have been around US$250,000. Following the advice of the National Cyber Security Centre, health board executives refused to pay, opting instead for the lengthy and complicated task of cleansing their servers and computers and restoring data from backups.

“By our estimation, the labour and other costs involved in remediating it would have been over $10 million,” says Armstrong.

“Should you pay a ransom? That’s a decision you have to make.”

Malicious indicators

The New Zealand Information Security Manual (NZISM) published by the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) makes clear that for all government departments and agencies, the buck stops with the chief executive when it comes to cybersecurity.

“If you're the chief executive of an agency that gets an attack, when you come up for your review with the powers that be, it's going to be on your head on the agenda,” says Armstrong.

But the fact remains that many government agencies, and the health sector in particular, remain vulnerable to attack until they can upgrade their systems and move some of them to better-protected cloud platforms.

Last year, the GCSB upgraded its Cortex security system, which is used by public-sector agencies and also applied to large private players such as the telcos, banks and power companies. The Malware Free Networks system in Cortex is designed to detect the malicious software responsible for ransomware attacks.

The National Cyber Security Centre says that by July this year, the system had disrupted more than 2000 “malicious indicators before they had the chance to cause harm”. Armstrong says the system is helping, but the increasing sophistication of hackers calls for action on all fronts, from CEOs and boards prioritising cybersecurity, to the government penalising bad behaviour with stronger legislation.

“The guys who were doing this are turning up to work in flash cars and suits,” he says. “They've got retirement plans, education plans for the kids.

“It’s all about the dollars with ransomware. As long as it is lucrative, they will keep finding better ways to do it.”