An important question in 2022 will be whether bureaucratic and political inertia over reclassifying conservation department stewardship land will be overcome.

It is a process that has rarely hit national headlines, but it is not inconsequential.

About 30% of conservation land is categorised as stewardship land. This is more than 2.5 million hectares or about 9% of all land in New Zealand.

Decisions about the use of this land matter more in some areas than others.

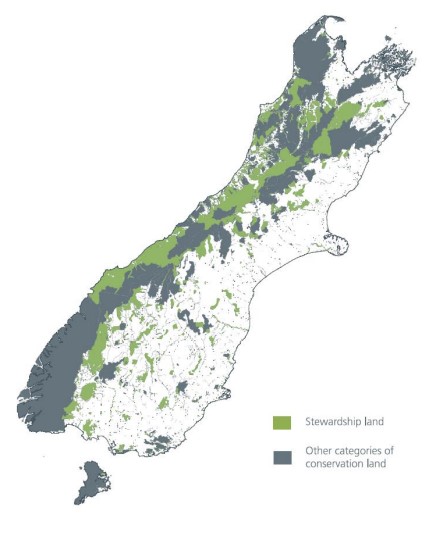

Most stewardship land is in the South Island, with approximately one million hectares on the West Coast. Considering much of the rest of the West Coast is also controlled by the Department of Conservation (DoC), such as in national parks, the process is a matter of some debate in the region.

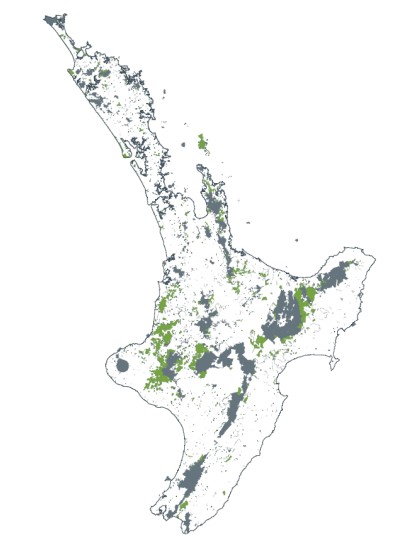

There are also smaller parcels of stewardship land across the North Island, primarily in Waikato, Taranaki and across the central North Island.

DoC’s progress in the area can be described as glacial, though that metaphor is losing its meaning as glaciers rapidly recede.

Land's not been assessed

When DoC was set up in 1987 and the Conservation Act passed, the government transferred responsibility for large areas of land to DoC. This was with the provision it would act as a steward of the land until its conservation value had been assessed and the land was reclassified or disposed of.

However, in the more than 30 years since the category of stewardship land was created, most areas have not even been assessed let alone officially classified or disposed of.

Only 100,000 hectares of stewardship land have been reclassified. Some were used to help settle Treaty settlements, other land has been added to existing national parks or conservation parks and more have been used for the creation of new national parks (eg, Kahurangi National Park and Rakiura National Park) and new conservation parks.

During the same period, over 40,000 hectares of land has been newly classified as stewardship land and brought into DoC control due to tenure review and land purchases.

South Island stewardship land in green (Source: DoC)

South Island stewardship land in green (Source: DoC)DoC is the centre of frustration

This apparent bureaucratic inertia has come despite urging by successive ministers and others to get on with it.

Environment commissioner Jan Wright said in a 2013 report reclassification should be a priority.

In 2015, the then conservation minister, Maggie Barry, requested guidance on how to speed the process up.

New Zealand First in the last government also pushed for the process to be given priority – its ministers said good land with little conservation value was doing little but growing weeds.

The Conservation Authority has also repeatedly expressed disappointment at the delays.

The decades of delays are frustrating to both conservationists and those who would like to free up the land for more productive use.

While stewardship land is managed by DoC for conservation purposes, some areas of stewardship land have significant environmental and conservation values. Some of this land is being undermanaged in comparison to National Parks.

Alternatively, there are some stewardship areas with very low or no conservation value and could be used more productively. It is difficult to tell how much land could fall in this category, partly because it is a matter of debate, but also because the work has not been done. North Island stewardship land in green (Source: DoC)

North Island stewardship land in green (Source: DoC)

Ruataniwha decision changed the game

DoC has taken potshots from both sides of the argument over the years. However, the urging of some conservationists to sort out the reclassification have become quieter in recent times because their fears over the lack of protection have eased.

While there used to be some legal uncertainty about the protected status of stewardship land, the legal battles over the proposed and now abandoned Ruataniwha dam gave rulings that made clear stewardship status had strong protections.

The ruling that stewardship land could not be simply swapped and flooded may have been about a specific site, but it had nationwide implications.

The suspicion is after this case what little sense of urgency DoC may have had about the issue disappeared.

There is some evidence of this. Under pressure from ministers in the last government, DoC said it would prioritise some areas and take a more systematic approach including a review on the West Coast.

In 2019, the West Coast conservation board warned such a review would be a “red rag to a bull” in the run-up to an election as it would raise hopes of freeing up land.

“The supreme court Ruataniwha Dam decision affirmed that a conservation land “stewardship” has almost all the protections of specially protected conservation land other than a ban on mining. As such, there is little immediate threat to these lands.

"Any review will ignite the West Coast debate that stewardship is just a holding category and that these lands could and should be allocated to private purposes and extractive industries,” the board said.

Since then, little if any land on the West Coast has been reclassified.

DoC’s apparent reluctance to deal with the issue is not entirely to blame, the process and law around reclassification is complex. As the West Coast board noted it also can be inflammatory.

Troubleshooters stymied

In May, acting conservation minister Ayesha Verrall set up two independent boards and gave them eight months to sort through the process in the South Island, including a number of policy and political heavyweights – notably former National minister Chris Finlayson.

The work got immediately bogged down, not least by legal action from Ngāi Tahu who felt they were not getting a big enough say in an issue close to the iwi’s heart – what happens to a vast part of the South Island.

Conservation minister Kiri Allan’s policy response to this was to add a Ngāi Tahu mana whenua panel to work with the two national panels and release a new discussion document proposing legislative reform.

One of the most telling parts of the document was how little progress has been made in reclassifying any of the more than 3,000 parcels of stewardship land.

Once again DoC said it was expensive and difficult. It also said it had yet to form the relationships needed.

“There are areas that and where extensive engagement is appropriate and complex partnership arrangements need to be developed. Some places are subject to competing interests, where tangata whenua, private individuals, commercial operators and businesses, and environmental and recreational advocacy groups may disagree on a proposed reclassification. This can lead to lengthy and complex consultation and even litigation.”

Looking forward to the 40th anniversary

DoC said while the current law does not prevent stewardship land from being reclassified, streamlining the legislative process “would achieve considerable economies of scale in reclassifying all 2.5 million hectares of remaining stewardship land”.

It said law changes or not, it would be trying to reclassify stewardship land soon, though the eight-month deadline given to the panels (which runs out this January) seems to have been quietly forgotten.

“The overarching aim will be to ensure reclassification protects conservation values more effectively while disposing of land with very low or no conservation values where appropriate.”

Though the department is already warning it expects some reclassification and disposal decisions will be legally challenged for various reasons.

“A successful outcome for this project would be that most of the 2.5 million hectares of stewardship land is appropriately reclassified or disposed of within the next five years.”

This would be just in time for the 40th anniversary of when the process started.