When our three closest allies announced last week they were forming a cosy military alliance, the scrutiny was on the nuclear submarine technology Australia will now gain access to.

But the AUKUS pact between the United Kingdom, United States and Australia also explicitly includes something potentially more significant – the sharing of knowledge around artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum technology.

AI already has well-established military applications, from simulating dog fights in flight simulators to controlling robots on the battlefield. Less well-established is the role of quantum computers, cryptography, photonics, sensors and communications, which are largely still in development but have huge implications for how the military will operate in future.

When we do actually have functioning quantum computers, which use the properties of quantum physics to store data and perform computations much more efficiently than our existing computers, we’ll be faced with a pressing problem. The so-called RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) algorithm used by millions of computers all over the world to encrypt and decrypt banking transactions, email messages and military commands, could be cracked.

Cracking encryption

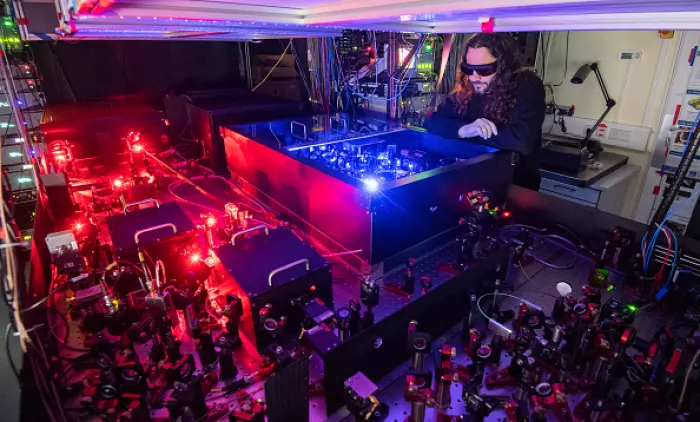

The scramble is on to find a replacement. The answer lies in quantum encryption, using the immense computing power of this new generation of computers to beef up digital security. New Zealand has a small but world-class research capability in quantum technology. Researchers in the field are dismayed that the AUKUS deal could see New Zealand excluded from accessing key emerging technologies.

“Let’s say someone builds a quantum computer and RSA doesn’t work anymore,” says David Hutchison, a quantum physicist and director of the Dodd-Walls Centre based at the University of Otago.

“You could easily then see the technology being put on a prescribed export list and no one else having access to it.”

Will our existing military relationships and Five Eyes membership allow us to gain access to cutting-edge new technologies? It’s unclear. We do have a bilateral agreement on cybersecurity with Australia, but it doesn’t currently include quantum technology.

Hutchison has urged the government to specifically add it to the work programmes we have with key allies to make sure we aren’t cut out of the loop due to AUKUS. The Dodd-Walls Centre, which receives $5 million to $6m in government funding annually as one of the country’s Centre of Research Excellence, forms the heart of our national capability in quantum technology.

It isn’t building quantum computers.

“We can't build all of the kit ourselves,” says Hutchison.

“What we need to do is make sure that we're good enough in some niche areas that we play a critical role in.”

Those niches include the development of quantum memory, storing and transmitting information in its quantum state. It could act as a sort of “quantum memory stick”, Hutchison says, or be sent over communications networks, even via satellite.

“If we had the quantum memory on the satellite and it was encrypted, then you could have the whole message encrypted from point to point, even if you were using your enemy’s hardware,” adds Hutchison.

Low-hanging fruit

Other areas Dodd-Walls researchers are working on is quantum communications, which could allow numerous small quantum computers to talk to each other and, the “low hanging fruit”, quantum sensors. Researchers are exploring types of quantum sensors that could be deployed to more easily monitor the status of undersea or pylon-based electricity cables.

Other countries have invested massively in quantum technology, particularly China, which has poured US$13 billion into its quantum research programme. Australia went big on quantum but has been criticised recently for losing its focus.

US companies and universities took the early lead on developing the quantum computers themselves. Last week, I had a virtual tour of Google’s Quantum AI campus in Santa Barbara California.

On a wall, a graphic of an Everest-sized mountain shows the Google quantum team’s roadmap for the next decade. The aim is to build an error-corrected quantum computer, with a high number of qubits or quantum bits, the basic unit of information in the quantum world. Dr Erik Lucero, who leads the Santa Barbara site and is responsible for Google’s quantum data centres, likes to compare quantum’s progress to the evolution of computing through the 20th century.

“In classical computing, we went from these kind of vacuum tubes, where it was very analogue, to these moments of actually having something in a digital sense,” he told me.

That ushered in the era of the transistor and then the computer chip revolution, which changed the world.

“We are on the cusp of actually getting to the transistor,” says Lucero, pointing his phone camera at a quantum computer that looks like an elaborate chandelier, with wires snaking off it for communicating qubits to and from Google’s Sycamore quantum processor and cryogenic systems to keep it super-cold.

Google wasn’t talking military applications, but the potential for quantum computers to tackle climate change.

Simulating nature

The computers are very useful for simulating nature, which could lead to major breakthroughs in chemistry and materials science, allowing more efficient batteries or the creation of new molecules allowing us to reduce the fertiliser we put on the land. Drug development is a big area of promise too.

The big dollars going into quantum technology around the world means there’s a good chance the efforts of Google and others will bear fruit in the next decade.

“Within ten years, there will probably be a quantum computing architecture that works,” says Hutchinson.

“By then we’ll have to have fixed our internet and our banking system, because RSA isn’t going to work. We can’t compete with Google and Microsoft, but we can complement them with the bits we do really well and which are critical to quantum computing working.”

Quantum technology is too important to be frozen out of. We need our government to make a concerted push to make sure AUKUS doesn’t see us miss out on cutting-edge developments in quantum and AI that could be central to our national interest.