If you weren’t reading the corporate obituaries last week you might have missed that Bridgecorp, the poster child for the hubris of the early 2000s financiers, was finally struck off the companies register.

Bridgecorp was one of the country’s biggest finance companies when it went belly up in 2007, owing almost 14,400 investors about $459 million. It also had a book value on its loans and property assets of $595.3m, something of an illusory total as we were to discover about many of the mezzanine lenders.

Like all the rest, Bridgecorp was lending to property developers and capitalising interest payments so it wouldn’t get paid until the end of the loan.

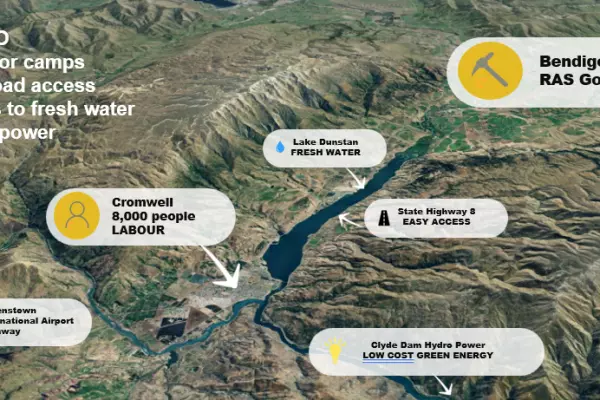

While its early 2000s TV campaign might’ve claimed it minimised the risk – think William Tell shooting a giant apple atop his son’s head from point-blank range – it was backing increasingly risky ventures, the most high profile being the Momi resort in Fiji, which was ultimately seized by the military after the 2006 coup.

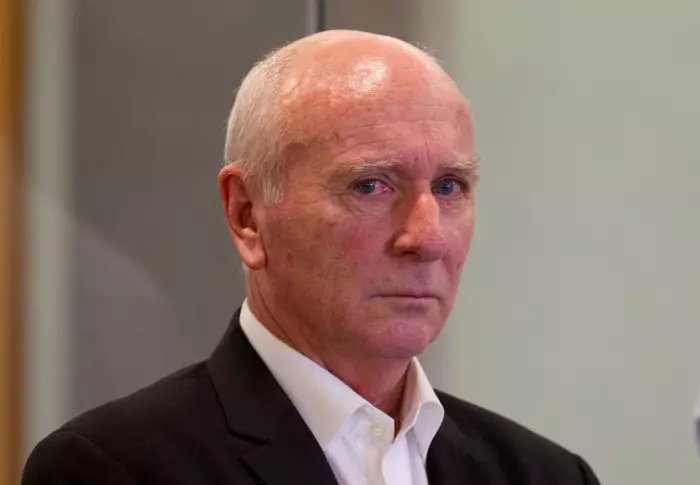

It’s easy to look back on Bridgecorp’s failure as an obvious outcome, given its board were convicted of making false statements in a prospectus and its principal Rod Petricevic and his lieutenant Rob Roest were found guilty of defrauding the lender to buy a luxury launch.

Petricevic was hung, drawn and quartered in the court of public opinion, roughed up in a Parnell restaurant and ostracised over his flashy displays of wealth. His attempt to get legal aid didn’t do him any favours.

Justice Geoffrey Venning found him lacking genuine remorse when sentencing him to six-and-a-half years in jail – an extra four months was added to the sentence for the fraud – but did cut him some slack for the mob justice meted out to him and his family.

Cold comfort

Not that that was any comfort to the out-of-pocket investors. Top PwC corporate undertakers John Fisk, Colin McCloy and John Waller all worked on the administrations at some point, extracting $117.3m in the decade-long receivership from loan recoveries, asset sales, litigation settlements and other receipts, of which $63.9m was repaid to the debenture holders, or about 14 cents in the dollar.

The liquidation drew out another $547,000 from director reparation and settlements – albeit $850,000 was promised – with $441,000 going to the investors, or 1.5 cents.

After almost a decade and a half, a total of 15.5 cents was clawed back for every dollar put in, not even accounting for the 1.9% annual pace of inflation over that time. Put another way, if the average amount invested by the 14,400 investors was $31,875, the average they each got back was $4,468.

That’s well off the initial 25%-to-74% recovery PwC estimated when it first got its hands on the books, but better than the miserly 10% maximum Venning foreshadowed in his 2012 sentencing of Petricevic.

Bridgecorp pulled the wool over investors’ eyes in the 2006 prospectus and paid above the odds for brokers to aggressively steer clients to their products, but the tide was going out by then, with lending all but drying up and new deposits being used to redeem existing investors.

However, like any Ponzi scheme, it struggled to keep the new money flowing in, with signs of the looming credit crunch starting to emerge.

That’s where dense investment statements proved to be ultimately unhelpful, hindering the ability of retail investors to weigh up the relative risk versus the reward they were seeking.

That was one of the biggest failures of the finance sector’s collapse. While the financiers offered a couple of extra percentage points to what was on offer from the banks – at the time a six-month term deposit was offering 7.96% – the risk investors bore was almost that of a property developer.

In essence, they should’ve been accepting something in the realm of 20% to properly reflect the level of risk they were taking. That kind of disclosure should’ve meant only the most foolhardy would’ve ploughed their life savings into those schemes.

Old lessons

This is why Bridgecorp’s ignoble demise is a handy reminder for a new crop of investors who haven’t been burned.

The opening up of capital markets through online platforms such as Sharesies has been a godsend to the local stock market that was struggling to convince a well-established network from unlocking new markets.

The problem is that the question of risk and reward seems very old fashioned in an environment where asset prices are so far removed from the fundamental value of the business, and investors have a burning desire for double-digit returns and warm fuzzies.

And it doesn’t even come close to addressing the increasingly unhealthy appetite for wholesale offers and unregulated instruments such as crypto, which are now finding their way into KiwiSaver funds.

The old rule of thumb is that you’d take 50 years of an assured 4% real return after inflation every time.

That’s a hard sell when managed funds are notching up 10%-plus returns year in and year out and with meme stocks shooting for the moon.

Probably not a bad time to visit the corporate graveyard and lay a wreath by the headstone reading: Here lies Bridgecorp and its capital notes paying 12% interest.