David Ross, the fraudster behind New Zealand’s largest Ponzi scheme, was released from jail this week after serving 6 years and 6 months of his 10 years and 10 months sentence.

We have limited information about Ross’s Ponzi activities because he pleaded guilty before evidence was presented in court.

However, we know that he played a major role in two failed investment management companies and there are clear lessons to be learned from his investment style, compliance structure and criminal activities.

Leadenhall Investment Management

Ross was born in 1950 and went to Waitaki Boys High. He moved to Wellington in the 1970s where he was employed as an equity analyst at ANZ. He was a quiet and unassuming individual who covered NZX-listed companies and played an active role in the New Zealand Society of Investment Analysts, now known as the Institute of Finance Professionals New Zealand.

In the early 1980s he joined Peter O’Neil at Leadenhall Investment Management and quickly became a co-owner of the Wellington-based company.

There were significant differences between Wellington and Auckland in the 1980s. The major banks and most of the large investment managers – including AMP, National Mutual, MLC, T&G, Government Life and others – were based in the capital city, while Auckland was dominated by individual investors.

The Wellington investment community had little time for Equiticorp, Chase and other high-risk Auckland companies. That was until Ross and O’Neil returned from a visit to the northern city and shocked Wellingtonians by acquiring large holdings in Auckland investment and property companies.

These purchases were consistent with Leadenhall’s marketing pitch: “If the market is not there, we go out and make it. We owe it to our clients not to sit back and wait for change.”

The Auckland investments were the first clear sign that Ross was a high-risk investor, a strategy that produced positive investment results in the short-term and attracted huge fund inflows for Leadenhall. The investment manager grew rapidly in the mid-1980s and Ross, who had become more confident after his Auckland successes, was a regular at the country’s up-market restaurants, usually hosted by brokers.

But the October 1987 sharemarket crash had a devastating impact on Leadenhall because of its focus on Auckland companies, which represented two-thirds of the failed NZX companies. Leadenhall also had a sub-standard property portfolio and poor administration.

O’Neil bought out Ross and Leadenhall was acquired by Southpac Investment Management in 1990 for a nominal sum. This purchase effectively bailed out Leadenhall but it also contributed to the demise of Southpac a few years later.

Leadenhall’s rise and fall clearly identified that Ross, who was the company’s main portfolio manager, was a high-risk investor with a strong preference for growth stocks, particularly small illiquid companies, and highly speculative Australian miners.

Ross Asset Management

In late 1989, Ross Asset Management (RAM) was established in Wellington with two shareholders, David Ross and his wife Jillian.

Ross adopted a lower profile in the early 1990s but he was often seen on Air New Zealand flights with a huge pile of broker reports, mainly covering Australian mining companies.

He also maintained an active social life, particularly long lunches that stretched into the early evening. He was a regular at Wellington’s Pravda Café & Grill, often in the company of brokers and other established investment industry participants.

We don’t have specific information on RAM’s investment style, but it is reasonable to assume that it was similar to Leadenhall because of the equity research reports Ross read, the brokers he dealt with and RAM’s subsequent problems.

Investors gave money to RAM and these funds were used to purchase shares that were held by RAM. The investment performance of these funds was reported by RAM without any independent verification or audit.

Ross came unstuck in late 2012 when the Financial Markets Authority raided RAM’s office following complaints from clients that they were unable to get their money back.

The regulator discovered that Ross had been running a massive Ponzi scheme whereby he overstated investment returns and paid money back to existing clients from money received from new investors, rather than from investment returns.

Ross claimed that the overvaluations were a mistake at first, probably in 2006, and he should have corrected them then.

The latest Parole Board report had this to say about Ross: “He said that at the time of the offending he enjoyed the admiration and respect that he received from his clients and the wider community. He said that unfortunately when he realised the portfolios were overvalued, he did not have ‘the guts’ to own up to his clients and kept it to himself.”

“He said he put on a false front and misled them to believe that things are going well because he did not want to lose the respect and admiration of others. Mr Ross also said that initially he was over-confident that he could put things right.”

Most major frauds start as small indiscretions and RAM’s attempt to correct the overvaluations, through high-risk investment strategies rather than adjusting client statements, was impacted by the 40 percent-plus decline in ASX metals and mining indices between September 2007 and December 2008.

Ross continued to put on a brave face as just a few weeks before the FMA raid he was seen talking and joking with brokers on Auckland’s Shortland Street.

Investors were supposed to have around $450 million worth of investments with RAM, including their original contributions plus investment returns. Their total final realisation was only $23.8 million.

Allan Hubbard

There are several similarities between RAM and Hubbard Management Funds run by the late Allan Hubbard.

HMF was a traditional investment management business run by Hubbard with client assets valued at $82 million as at March 31, 2010, but the statutory manager assessed these to be worth only $48.75 million in January 2011.

The final distributions were well above $48.75 million but HMF was totally flawed because it had inadequate accounting standards, investors were allocated shares and other investments that didn’t exist, portfolios were overvalued in client statements and more than 50 percent of client funds were invested in companies associated with Hubbard or in high-risk unlisted companies.

Even though Hubbard was over 80, and admitted privately that he was far too old for investment management, individuals continued to give him money because he was seen as a good guy who donated to charity, supported local Timaru businesses and was one of the country’s most highly regarded individuals.

Ross and Hubbard reported inflated investment returns to clients because they both knew that, as unregulated one-man operations, they would lose funds if they reported poor returns.

Current situation

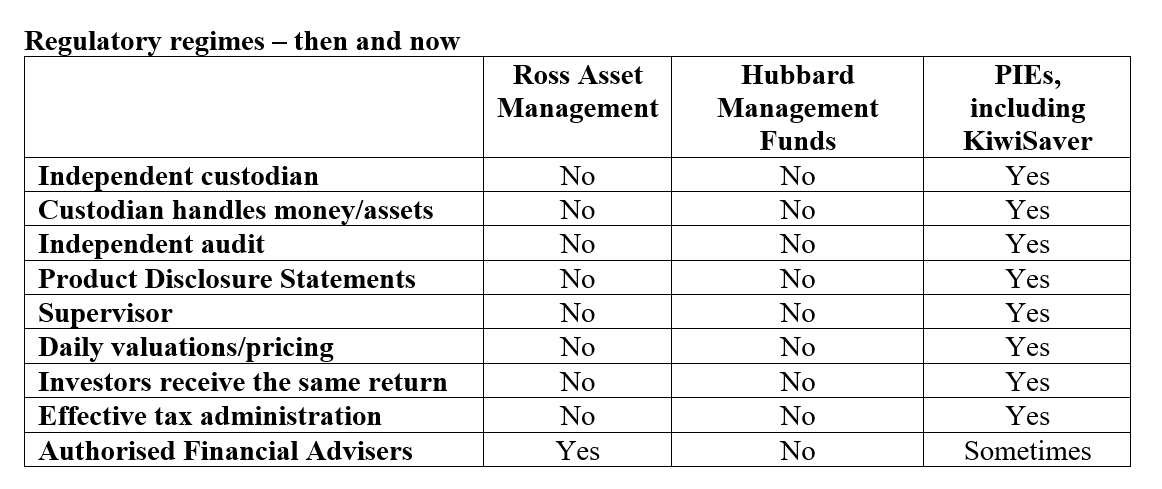

The good news is that there has been a substantial improvement in regulation since the RAM and HMF debacles, as demonstrated by the following table.

PIE funds, including KiwiSaver funds, now have numerous requirements to protect investors against fraud whereas RAM and HMF only had Ross as an authorised financial adviser. This qualification didn’t count for much considering the huge losses RAM investors suffered.

Nevertheless, individuals need to be careful because unscrupulous charmers, who don’t meet PIE requirements, will try and convince vulnerable people to hand over their hard-earned money.

Investors should also be careful of Ross, who plans to move to a small unidentified New Zealand town.

The Parole Board believes he has a low risk of re-offending. Let's hope he's not thinking third time lucky after his Leadenhall and RAM debacles.

Disclosure of interests; Brian Gaynor is non-executive director of Content Limited, the publisher of BusinessDesk, and Milford Asset Management.

Value quality journalism? Subscribe to a BusinessDesk today. We offer a free 10-day trial. See more details on our subscriptions here.