Welcome to My Net Worth, our regular column on the lives and motivations of our country’s top business, legal and political people, in their own words.

Susan Peterson has a formidable CV. She’s an independent director of New Zealand tech company Xero, chair of the board of NZX-listed tech company Vista, a director of Trustpower, Property for Industry and of NZX-listed aged-care provider Arvida, and co-chair and shareholder of fast-growing sanitary products company Oi (the Organic Initiative). She is also on the board of trustees of the advocacy organisation Global Women, and her career overlaps a little with that of her brother Mark Peterson – he’s the NZX chief executive and she’s on the New Zealand Markets Disciplinary Tribunal.

I was born and educated in Lower Hutt and went to a small girls’ school called Chilton Saint James. I think we had only 300 girls, and that was from preschool right through. This actually meant some subjects were not really on offer unless you were prepared to go to the boys’ school down the road. You had to sort of pick yourself up and get on with it. If we wanted a sports team, you had to persuade each other to join, which was quite fraught, and it could be frustrating, but looking back, it was a gift.

I played tennis all the time at school. I either played for my club or representative tennis and it was before and after school and on weekends, so I was pretty focused on that. I had a pretty sheltered childhood and, with also going to a small school, it was fairly unworldly. I had a lot of growing up to do.

I have two siblings, Mark and Richard. Having brothers really helped me. I grew up with a boy’s lens on the world domestically; you're pushed around and shoved around and pushed on your expectations, and I think that was really important – given I went to an all-girls school – to keep that level of balance and energy.

In the 1980s, I was lucky enough to get a job in the summer holidays in accounts payable at Wellington Newspapers. I sat in a glass cubicle and collected cheques and wrote receipts, and it would have been fine if it wasn’t for my supervisor, a woman who smoked non-stop. But I was massively grateful for the job because it was hard to find any employment.

I don’t look at my life through the lens of having business achievements. My career has been progressive and incremental over time. I look at what I’m doing in the moment and try to do a good job, and positively impact the folk around me, and that’s led to the next opportunity.

One thing, if I look back, which I didn’t realise at the time was impactful was when I needed to ask for parental leave for my own domestic situation. I was in a privileged position of being in a law firm that could pay parental leave, and I could negotiate it based on the financial deliverables I was doing for that organisation to provide a business case to get the money, which I really needed. It was a good outcome, but I’m very mindful that so many women of that time would have enjoyed it but didn’t have the ability to ask for it or be heard.

I don’t have any regrets in my career, but I've had significant failures. I’ve been part of things that objectively haven’t gone well at all. At the risk of sounding cheesy, there have been moments when you work through the failures well enough, and learn from them, and they actually end up being the thing that creates the next opportunity. I see that as part of the reason I don’t really celebrate the highs and over-sweat the lows; it’s all par for the course.

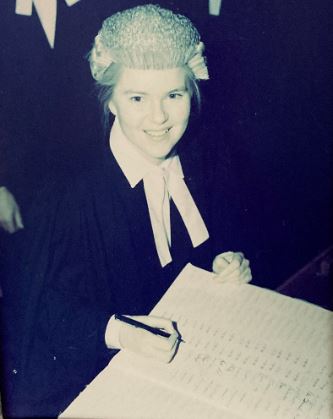

Susan Peterson at her admission ceremony in September 1992.

Susan Peterson at her admission ceremony in September 1992.

Those who are closest to me know I have a tendency to worry where there could be potential negative people impacts. I work super hard to soften those impacts. I will lose sleep over that, but in terms of things that fail and business models that haven’t worked, I don’t enjoy them but I know they can create opportunities if you deal with them OK.

There's not a lot of financial reward to being a director. There's quite a lot of liability, but most importantly, you can end up with your name in the headlines and these brave people take that on because, actually, the country needs it.

I look at the hours companies are asking me to dedicate and multiply those hours by three, and then I do my calendar across what that looks like, making sure I’ve got some give in the day for emergencies that will turn up. For me, I'm at capacity now.

There are a lot of directors I admire, but John Waller [the late BNZ and Eden Park Trust chairman and Fonterra board member] was epic. The reason is that he supported others when they were going through real strife. You would get little telephone calls from him and he would say, “Look, don’t tell me anything about the problems but I’ve been thinking and have you thought about this? Have you thought about that?” He wouldn’t want anything in return. He would end the call by saying when someone else is in strife, pick up the phone. He did that for me in a situation where it was a bit too tough. I would like to emulate those attributes and gifts he gave me.

My hardest business lesson is learning that the way you do things is not always the way that others want things to be done, or how it might be used against you, or that it should be managed in a way you would instinctively prefer not to do so. To be relatable requires a degree of transparency around things that have gone well and things that haven’t. Some people are uncomfortable talking about things that haven’t gone so well.

I've just taken up golf again, and I bought myself a serious sort of e-bike – well, a mountain bike – with the idea I could do more mountain biking, which should be fun. I wouldn’t navigate the Auckland roads to go anywhere, though; that would be taking your life in your own hands.

As told to Rebecca Stevenson.

This interview has been edited for clarity.