I give to charity, I’m on the board of a charitable trust and run a not-for-profit organisation.

It is from all these perspectives – as a donor, director and chief executive – that I look at the proposed changes to the Charities Act with optimism, tinged with nervousness.

Some of the nervousness is due to not knowing exactly what the government will do. The details of the changes to the Act have yet to be announced.

But the optimism comes from knowing the goal of the reforms is to promote transparency and accountability in the sector – transparency about an organisation’s purpose and funding, and accountability on delivery against that purpose and how funds are accumulated and spent.

Transparency is good.

With my donor hat on, more transparency will help me choose which charities to give to, with an understanding of how my dollar will be used.

With my director’s hat on, it will help clarify to my board what our responsibilities are when we're reporting on how we deliver on our organisation’s purpose.

With my management hat on, I am pleased to see purpose being given pride of place in the discussion.

Purpose drives strategy

As chief executive of the Institute of Directors (a not-for-profit membership body), I support the centrality of organisational purpose. “Determining purpose” is the first pillar of the IoD’s Four Pillars of Governance Best Practice.

That the importance of purpose is recognised in the proposed reforms is good. Having a clear purpose is a driver for success in all organisations – charities, not-for-profits (NFPs) and for-profits alike. It is the first step in creating a strategy for success and integral to the development of a sustainable business model

But, at this point, my nervousness resurfaces because, in the non-profit sector, the idea of a sustainable business model is sometimes a pipe dream.

Charities rely on the uneven income of donations. Not-for-profits service customers who may pay for a membership or a service, but who rightly expect that to come at an affordable price.

Most organisations in both spheres maintain limited reserves, compared to their for-profit peers. They usually can’t raise bank loans in order to take on important projects that enhance the sustainability of their business models – upgrading an IT system, for example.

As an aside, creating sustainable business models in the charitable sector is likely to require more cooperation – even mergers – between similar charitable groups.

New Zealand has a lot of well-meaning people working hard to deliver necessary public goods and services. But there is scope for some to join forces, creating economies of scale.

In any case, any changes to the rules around accumulated funds must continue to allow not-for-profits to build up assets – perhaps over many years – in order to deliver major projects or ride out economic shocks.

Nobody likes to think organisations are able to masquerade as not-for-profits while operating in almost the same way as commercial enterprises. That is one of the issues identified in the “The Business of Giving” series of articles, and I hope the final shape of the Charities Act reforms helps the Charities Board make transparent and consistent decisions on registration and deregistration of charities.

Growing the pot

When I give, do I want to give my dollar to help one person? Or do I want a charity to turn that into a three-dollar impact? As a donor, director and manager, I would hope for the latter, and I understand that may require my dollar to be invested rather than spent directly on services tomorrow.

But the final shape of the reforms must support, rather than hinder, the sustainability of not-for-profits, including charities. This is vitality important for New Zealand. In effect, we ask not-for-profits to fill in gaps on our society on a voluntary basis without good resourcing. No easy task.

Oliver Lewis' recent article on BusinessDesk, “Charity hospitals, philanthropists covering health system gaps”, brought home very strongly that without support from not-for-profits, even our highly government-funded health services would fail to meet society's needs.

Maintaining economic viability and managing limited resources is challenging for not-for-profits' boards, especially when an economic shock makes fundraising more difficult, or reduces a traditional income stream.

We need our not-for-profits to invest in people, infrastructure and training if they are to deliver on their purpose. We need our charitable organisations, in particular, to have the time and resources to innovate as poverty and the pandemic continue to impact – and as they find themselves picking up the pieces of people’s lives.

We don’t value and respect governance in the not-for-profits sector enough, or realise how hard it is to govern, particularly for chairs. Setting up an effective strategy, monitoring delivery against purpose and ensuring an organisation stays on the right side of laws and regulations can be extremely challenging.

As a donor, director and executive, I hope that the reforms turn out to be – dare I say it – fit for purpose.

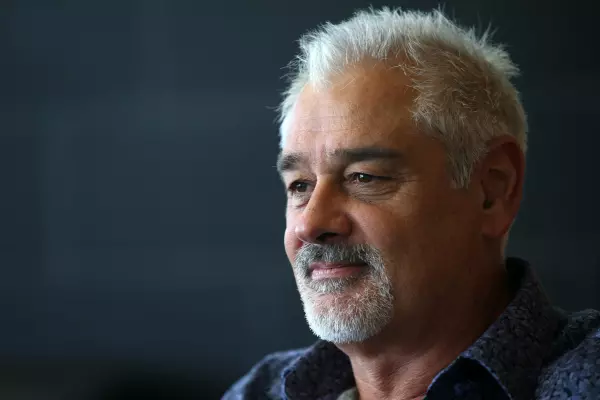

Kirsten Patterson is chief executive of the Institute of Directors.