America’s 38th president, Gerald Ford, said a lot of things but one of the best was his quip about lunch: “The three-martini lunch is the epitome of American efficiency,” he opined. “Where else can you get an earful, a bellyful and a snootful at the same time?”

Ford was, of course, talking about the long lunch or, as Esquire magazine rebranded it in 1979, the power lunch, where blokes (and yes, it was usually only men) spent hours dining on gin and ideas for ad campaigns, book deals and financial and legal issues.

But, thanks to repeated recessions, stricter working environments and changing attitudes to alcohol, the long lunch has gone the way of the dodo.

Where once men who looked as though they’d stepped off the set of Mad Men would chew over deals and prawn cocktails, working lunches are now usually “al desko” – wilted salads or sandwiches eaten in stuffy meeting rooms or dropped onto keyboards. Many office drones can barely leave their desk to go to the toilet let alone for an overpriced steak at a fancy restaurant around the corner.

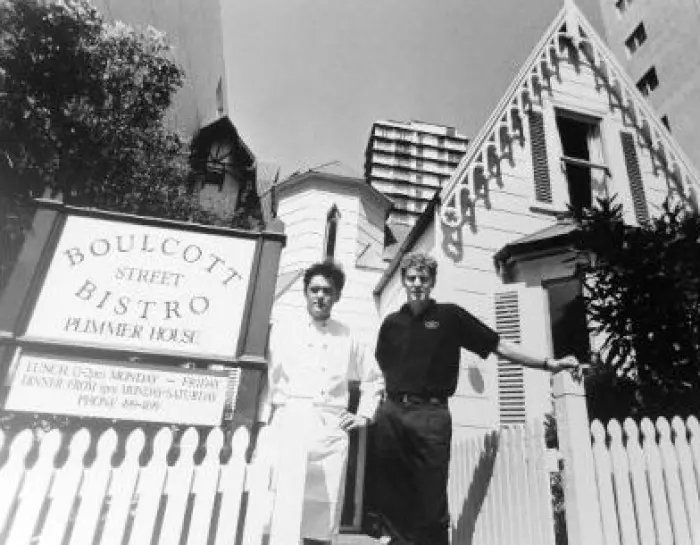

And that’s a shame, says Mike Egan, owner of Wellington restaurant Monsoon Poon and co-owner of the Boulcott Street Bistro.

He would say that, having skin in the game – he’s been in the hospo industry since he was 18 and president of the Restaurant Association of New Zealand for the past 12 years.

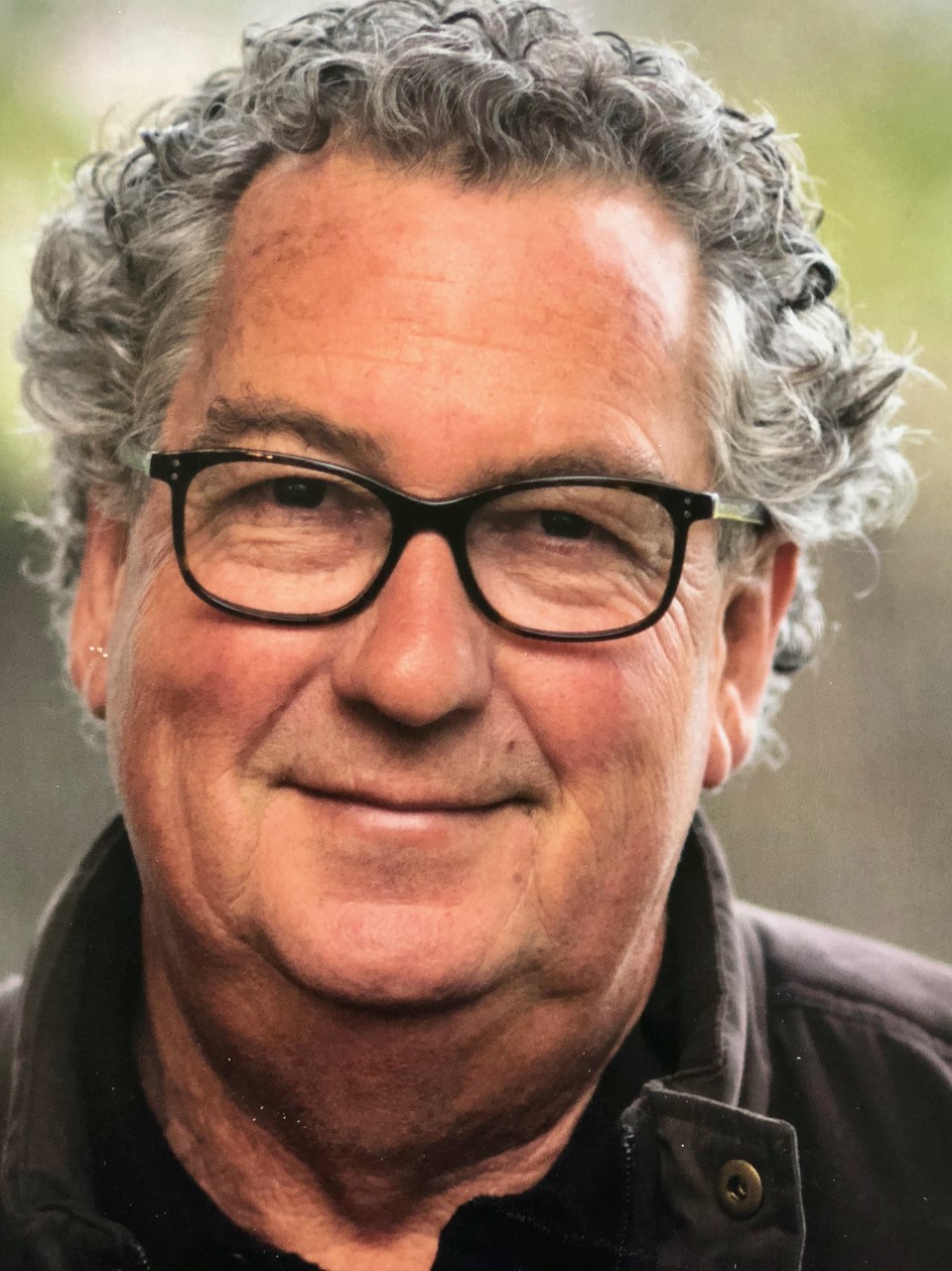

Mike Egan, co-owner of Monsoon Poon and Boulcott Street Bistro.

Mike Egan, co-owner of Monsoon Poon and Boulcott Street Bistro.

The long lunches of the 1990s and 2000s, Egan believes, were a chance to build relationships. “People could spend time away from the office and really get to know each other. And they could savour good food and wine. Restaurants aren’t food factories; they’re there to be enjoyed and a long business lunch was the chance for that to happen. Nowadays, it’s all digital.”

Having done his OE in a private members’ club in London, Egan was used to lunches rolling into dinner times. When he returned to Wellington, he opened Dockside Restaurant, which became a hub for the city’s suits. And where the suits went, so followed the outrageous behaviour.

“Often a table of 10 would spend $5000 on lunch, most of that on alcohol. One time, a group of accountants let loose and started using plates as frisbees, throwing them into the sea. I charged them $30 a plate and the next day got a diver mate to go down and collect them all.”

When Egan opened Arbitrager, the wine bar in Featherston St, it, too, became the hub for well-lubricated lunches.

“We had a group of oil-company execs once who spent 30K, drinking $500 bottles of Krug. The food part of their bill was something like $200!”

These days, laments Egan, lunchers are in and out in an hour. “And they often won’t even have a glass of wine.”

Someone who knows all about long lunches is Kim Thorp. As creative director of Wellington’s Saatchi & Saatchi from 1985 to 1999, when it was frequently voted one of the 10 top advertising agencies in the world, he oversaw big-budget campaigns such as Telecom’s Spot the dog and Toyota’s Barry Crump “bugger” ads.

“Put it this way: there weren’t a lot of lunch-boxes at Saatchi! We’d pretty much ate out every day,” recalls Thorp, who now runs his own consultancy from Hawke’s Bay and co-owns Black Barn Vineyards.

Kim Thorp, former creative director of Saatchi & Saatchi Wellington.

Kim Thorp, former creative director of Saatchi & Saatchi Wellington.

While he admits alcohol was regularly involved, he stresses it wasn’t about the bubbles and lavish lunches: “Our office was manic and there was no way you could sit down and have a good chat or think deeply about campaigns. So, we’d bugger off to a restaurant to shoot the breeze and create great advertising.”

Thorp’s two favourite spots were a small Malaysian restaurant that no longer exists (“It wasn’t flash enough for any of the agency suits to be there”) and Il Casino, run by the late Remiro Bresolin, which was flash.

“We created some great adverts at Il Casino. Remiro knew which tables were our favourite, where we’d cracked successful campaigns, so he always kept those for us. In those days, it was the HQ of ad agencies, with both suits and creatives dotted around the place.”

One of Thorp’s team would always order chips, which annoyed Il Casino’s Italian chef. “One day, the poor waitress came out crying and the chef had whacked her because we’d ordered chips again. We immediately gave her a job on reception and she went on to have a great career in advertising.”

There was also the team member whose wife found him asleep with one arm in the cat flap – he had tried to enter the house inebriated. “We worked hard and played harder.”

Other favoured lunch spots included Boulcott Street Bistro, Bacchus and Martin Bosley’s Yacht Club.

“These days, business is so transactional that people don’t see restaurants as a domain for work any more. That’s a real shame, especially for the restaurants themselves.”

When I speak to executive coach Sally Duxfield, she’s driving to a client meeting. “I’ll drive two hours there, have a half-hour meeting, then drive back, because I really believe in the value of face-to-face contact,” she says.

It’s part of what we’ve lost with the death of the long lunch, Duxfield suggests.

“Business lunches these days are all sightly dull and often there’s not even a glass of wine. There’s a sense that a long lunch is wasting time when you could just as easily do things electronically rather than driving somewhere, finding a park and waiting for your food. People don’t tend to value spending time with others around the table the way they once did.”

But when you’re not meeting face to face, you can lose so much of the nuance of observing micro-behaviour, of whether the person you’re talking to is engaged with what you’re saying. “It’s hard to be that present and mindful when you’re on a Zoom chat,” says Duxfield, who has motivated and led high-performance corporate teams for 25 years.

She admits today’s transactional business practices can be more effective from a time perspective, but the casualties include strong relationships and loyalty.

“In leadership terms, relationships are everything. When you had lunch with your clients, you got to know them and they were generally loyal to you. When we settle for shallower relationships, we settle for less loyalty. The consequence is that clients may head elsewhere.”

PR legend Jane Vesty credits Wellington’s long lunches of the 1990s for much of her success in New York with SweeneyVesty, the PR firm she co-owns with husband Brian Sweeney.

Balclutha-born Vesty started the business in 1987 and says she was taken under the wing of top creative agencies such as Saatchi and Colenso.

“I was young and just starting out in business and they really helped me,” she says by phone from a snowy New York, where she’s been based for 15 years. “I would never have had the experiences I’ve had in the US if it wasn’t for those guys.”

The 1990s, says Vesty, was the time when integrated communications really started, with advertising agencies wanting to connect with all stakeholders. Which is where PR came in.

But the long lunches were nothing like the Absolutely Fabulous perception of PR, all Bolly and no work.

Jane Vesty, co-owner of PR agency SweeneyVesty.

Jane Vesty, co-owner of PR agency SweeneyVesty.

“Long Wellington lunches were about moving the office to a restaurant,” says Vesty. “Creatives were under a lot of pressure to do the best work they could for their clients and to keep winning awards, so if they could let off a bit of steam while working, then that helped the creative process enormously.”

Vesty says some of the best restaurants for getting deals and campaigns done included Petit Lyon, Il Casino, Brasserie Flipp and the Angkor, as well as Ruth Pretty’s Marbles in Kelburn and Two Rooms in Miramar. “The restaurateurs knew us and loved that we supported them.”

If Vesty knows of any outrageous behaviour that went on at those long lunches, she isn’t telling. But she does admit they were a lot of fun.

“Look, if sometimes doing karaoke at lunch helped the creative process, then so be it! But if anyone had a few too many cocktails, we’d usually put them in a cab and send them home to sleep it off.”

Asked if business these days has been affected by the death of the long lunch, Vesty says yes and no. “We’re fortunate that we have so many different modes of communication now, so we can decide to meet by Zoom or over lunch or a coffee. While you lose that face-to-face relationship building of a lunch, meeting digitally can save time and sometimes be more effective. I’d never want to go fully digital, because I enjoy a good lunch, but the end of the business lunch isn’t all bad.”