“Give it up for the band!" hollered Van Morrison from the stage at King John’s Castle in Limerick.

At that, the legendary Irish performer grabbed the gold saxophone he had been periodically parping on over the previous 90 minutes, abruptly turned on his heel and disappeared into the wings as his eight-piece backing group obligingly carried on jamming and the crowd yelled out for more.

Me, too. I had journeyed to be there with a couple of thousand Irish fans because, like so many Kiwis locked away from the world for the better part of three years, I had felt the quivering need for a huge splash of “revenge travel”.

In my case, this had meant 10 days – or, more to the point, 10 song-filled nights – of back-to-back musical activity in various locales across the Emerald Isle.

Live music was an obvious thematic choice, New Zealand having been particularly dismally served on this front since at least 2019; besides, it’s so easy to organise musical interludes online these days that a diehard fan would be a mug not to take advantage of the technology.

That’s how I found myself on the island of Ireland, sitting in on organ recitals in cobwebby churches, hanging out in raucous blues bars, listening to music being made inside celebrated recording studios, soaking up the rock’n’roll landmarks, and going to a couple of other big-ticket outdoor shows.

Fans of Van Morrison gather in the courtyard of King John's Castle in Limerick for their hero's concert to begin. (Image: Getty)Morrison’s mystically charged, tersely voiced performance in the courtyard of the 13th-century landmark overlooking the inky waters of the River Shannon was always meant to be the icing on the travel cake.

Fans of Van Morrison gather in the courtyard of King John's Castle in Limerick for their hero's concert to begin. (Image: Getty)Morrison’s mystically charged, tersely voiced performance in the courtyard of the 13th-century landmark overlooking the inky waters of the River Shannon was always meant to be the icing on the travel cake.

What I hadn’t fully appreciated while planning the itinerary was how, when it comes to music and Ireland, Morrison actually is the cake. Honestly.

From Belfast to Limerick, it’s hard to turn sideways without bumping into the shadow of the 77-year-old bluesman, to the point he became something of an itinerant Kiwi’s virtual travel guide.

I started out in Belfast, a sunken industrial city set amid horseshoe hills, near the working-class suburb of Bloomfield. Which also happens to be Morrison’s childhood stomping ground.

The son of an electrician, he grew up here in a small little red brick house at 125 Hyndford Street. His mother was a dancer.

Oh, and look yonder (you find yourself saying things like “yonder” after spending any appreciable time in Ulster), there’s Cyprus Avenue, which also happens to be the title of the snazziest track on his 1968 pastoral masterpiece, Astral Weeks.

In Belfast, where Van Morrison was born and raised, fans can follow a trail that takes them to sites where he gained inspiration for many of his songs. (Image: Getty)

In Belfast, where Van Morrison was born and raised, fans can follow a trail that takes them to sites where he gained inspiration for many of his songs. (Image: Getty)You can savour all this by taking the Van Morrison Trail, a three-hour walking lyrical journey, after downloading the free directions to the settings of many of the old songs.

And what do all those old songs mean in 2022? I have no idea and, if I did, I wouldn’t tell you. Neither would Van Morrison, not now and not ever.

“My records do not require a lot of thought of, 'What is this?' and 'What is that?',” he once explained. “That would be too contrived for me.” How very Irish.

Still, it’s handy to draw a bead on the references. The Morrison Trail also figures as a welcome bit of physical exercise for those who may have spent more time than they bargained for inside certain European airports waiting for flights that either never came or didn’t depart with me on board.

That’s uncharitable of me to say, I know, so it was perhaps good for the soul that my next stop happened to be the city’s most romanesque church, the mighty Belfast Cathedral, to grab a seat in the Anglican pews and enjoy a few hymns.

The internet has helped to give Dubliner Dermot Kennedy a global legion of admirers. (Image: Getty)

The internet has helped to give Dubliner Dermot Kennedy a global legion of admirers. (Image: Getty) In concert, Kennedy’s voice gains an impressive sense of scale as he ploughs through his brief back-catalogue, with the impressive assistance of a three-piece band and backup singers.

As someone who doesn’t quite fit his natural demographic, I soaked up the performance with surprising pleasure out on the green fields of the city’s outdoor Belsonic music festival venue, the sky above a riot of orange.

Ah, the sectarian green and the orange. And how striking to be among 25,000 mainly young, entirely ecstatic female fans in the Protestant heartland of the British province, where everybody was going bananas over a Catholic boy from the republic.

On this front, at least, the fruits of the Good Friday Agreement feel rather promising, as did one of Kennedy’s signature tunes, a sweet and anxious cover version of Van Morrison’s Days Like This.

Border? What border?

The following morning, I took the two-hour train trip from Belfast to Dublin. The journey ferries you across what used to be the most-fortified border in the developed world but which today feels like one of the most imperceptible.

In travel, as with entertainment and, increasingly, business, it all feels more and more like just the one joint. Yes, yes, I know, hard borders and Brexit and all that, but still.

Is there a more musical city on Earth than Dublin? If there is, I’m yet to experience it.

Those interested in quantifying the claim can head over to the vape- and perfume-scented Irish Rock'n'Roll Experience Museum.

Located in the Temple Bar neighbourhood, it offers an interactive tour of a dimly lit studio and stage at the achingly hip Button Factory. Along the way, you pass under galleries of Irish musical eminences. Including you-know-who.

At the museum, I asked the tour guide whether people in Dublin preferred to refer to Van Morrison as the Belfast Cowboy or just simply Van the Man.

“Oh,” she replied brightly, “we just call him the arsehole.”

She was referring affectionately to the singer’s famously cantankerous style.

The Windmill Lane Recording Studios in Dublin welcomes visitors such a David Cohen keen to check out its operations. (Image: Supplied)

The Windmill Lane Recording Studios in Dublin welcomes visitors such a David Cohen keen to check out its operations. (Image: Supplied) Morrison’s style was also in evidence a few kilometres down the road at the Windmill Lane Recording Studios, which offer one-hour immersive tours of the country’s most prestigious recording operation.

Windmill makes much of what it calls “the extraordinary breadth of acclaimed material” to have been recorded there over the years.

That roll includes six of U2’s albums (including the band’s breakthrough work, The Joshua Tree), Kate Bush’s Hounds of Love, and titles by David Bowie, the Waterboys and the Rolling Stones.

Morrison’s luminously ragged collection of the folk classics, Irish Heartbeat, was also mixed at Windmill. He so enjoyed the sessions that he ended up buying the studio outright, selling up again last year.

Later, as the moon was rising over the crisp and cold River Liffey, which bisects the Irish capital, I made my way to Trinity College, one of Ireland’s pre-eminent institutions of higher rock.

Outside the famous university’s western gate, famously, are bronze statues of the long-departed writer Oliver Goldsmith and philosopher Edmund Burke.

Dublin's status as a hugely popular international music destination is reflected in visits by the likes of English-Ugandan singer Michael Kiwanuka. (Image: Getty)

Dublin's status as a hugely popular international music destination is reflected in visits by the likes of English-Ugandan singer Michael Kiwanuka. (Image: Getty)

Inside, very much alive on the night, was the singer-songwriter Michael Kiwanuka. This London-born artist of Ugandan background has pretty much been on every critic’s playlist for the past couple of years.

Kiwanuka is not Irish, but that’s part of another point about Dublin: it’s an incredibly popular international musical destination.

Like Ray Charles – whose musical influence he has acknowledged – the 35-year-old Londoner and his ace band play “all kinds”, whether gospel, psychedelic or soul. But Kiwanuka’s breakthrough work – some of which is showcased at the Dublin show – invites favourable comparisons to Veedon Fleece-era Van Morrison, and if you don’t believe that, then listen to the Afro-horn-influenced Tell Me a Tale, and then let’s argue about it over a Guinness.

On life and death

The most sensible way to get from Dublin to County Sligo is by train, but give a boy a brand-new rental car (thank you, Irish Tourism) and he certainly isn’t going to be found inside a carriage.

The next day, I drove out of the capital, purring west along a highway as straight as an arrow for the next four hours, the urban landscape giving way to woods giving way to farmland giving way to the crashing vistas and spooky cliffs of the west Atlantic coast.

Under the arcadian shadow of Benbulbin Mountain, I pulled over at little St Columba’s Church to visit the gravesite of its most celebrated Protestant parishioner, WB Yeats. I walked across the scenic churchyard until I found a simple grey headstone:

Cast a cold Eye

On Life, on Death

Horseman pass by

Which reminded me, first, of how I first encountered the same artist by way of Morrison’s music, specifically his jazzy musical reading of Yeats’ poem Crazy Jane on God.

Which also reminded me that I was running late for the big show.

In Drumcliff, County Sligo, David Cohen stopped to visit the last resting place of one of Ireland's literary giants. (Image: Supplied)

In Drumcliff, County Sligo, David Cohen stopped to visit the last resting place of one of Ireland's literary giants. (Image: Supplied) I walked back to my car. The highway beckoned for another four hours until Limerick hovered into sight. I parked near the River Shannon and hurried over to the venue.

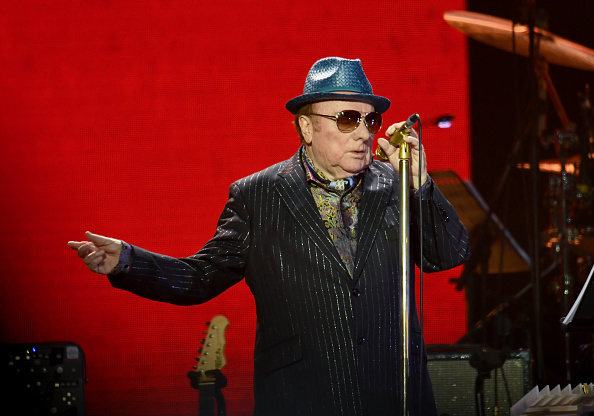

Others were soon streaming in, too, including eight instrumentalists and – here comes the knight – the besuited guy himself, decked out in reflecting shades and raffish hat and with a suitcase full of hits, which he drew on heavily for the next hour and a half.

On this particular crisp night, those hits would include a tender version of Have I Told You Lately? and a delicately piano-based rendering of Carrying a Torch, one of his most supple ballads from the early 1990s.

Best of all was a reconstituted packaging of the lyrically rich rocker Full Force Gale, a standout originally recorded with Ry Cooder on the gorgeous album Into the Music. Morrison's eight-piece group played like a full-force gale, too.

And the band played on

And then he was gone again, without so much as a word of goodbye, just the “Give it up for the band!” line. Encores be blowed.

But for the next 15 or so minutes, the band continued playing a medley of old hits, most notably a fully imagined reworking of the song Gloria, a weird but transfixing drum piece that sounds like reggae but is actually the song Moondance, and a sensational guitar piece from long-time sideman Dave Keary.

And where was the great Irish artist himself? Probably back at his hotel suite, I assumed. Not that it mattered. In this particular rolling country, Van Morrison lives everywhere. Give it up for the land, indeed.