Contrary to popular belief, the New Zealand housing market is vulnerable to booms and busts as it is highly dependent on credit, population movements (mainly migration), and other variable factors.

New Zealanders have an especially positive attitude towards residential property because it has been a long time since we last had a major decline in house prices.

In addition, housing markets have relatively long cycles and information on previous downturns is hard to find, particularly compared with sharemarket busts.

However, there have been many global housing bubbles in the past, including:

- The Florida land boom of the 1920s, which was strongly influenced by the expansion of the railway to West Palm Beach, Miami and Key West. Thousands of residential subdivisions, palatial estates and ornate apartment complexes were built but the bubble burst after the three major railway companies curtailed their schedules because of congestion.

- Land prices in Japan, particularly in Tokyo, increased dramatically between 1986 and 1990, mainly because of a huge expansion in credit after the Bank of Japan lowered its interest rate to 2.5%. The Tokyo Residential Land Price Index soared 135% between 1986 and 1990 but crashed after the bank raised its interest rate to 4.25% at the end of 1989.

- House-price bubbles in Ireland, Spain and the United States in the early 2000s were also fuelled by easy money. The Irish residential property market collapsed dramatically during the Global Financial Crisis after several banks had to be bailed out. National house prices sank 50% and Dublin prices plunged almost 70%.

New Zealand has also had property bubbles, including the commercial property boom and bust of the 1980s and Auckland’s massive speculative bubble in the early 1880s.

This column focuses on the latter, which brought Auckland to its knees and contributed to a decade-long economic depression.

Most of the information is derived from government statistics, documents and books, particularly by Russell Stone, who has written numerous histories of early Auckland.

City father John Logan Campbell wrote that Auckland property was “utterly unsaleable” after the 1885 crash and Stone noted that “banks and lending agencies became landowner by default of a surprising range of city and suburban properties”.

Early Auckland

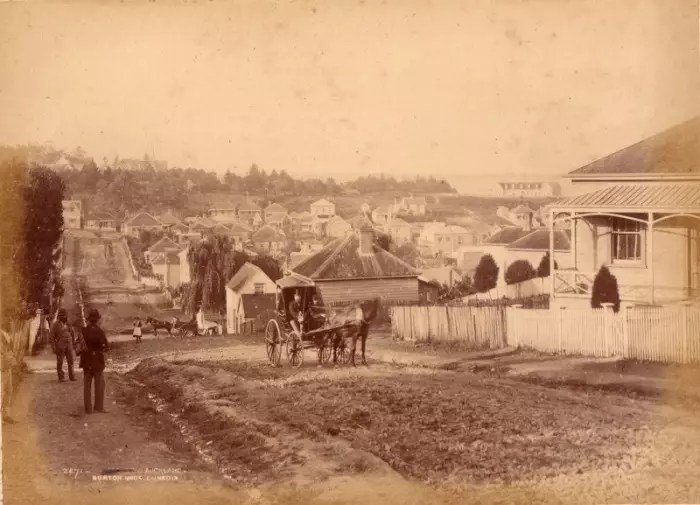

Auckland was a totally different place 160 years ago. In 1861, its population was only 8000, mainly confined to Queen Street and the Ponsonby, Karangahape and Parnell ridges that surrounded it.

Beyond these ridges was rural land, now overtaken by the city’s sprawling suburbs.

Auckland had no effective water system and the Ligar Canal, formerly known as Waihorotiu Stream, ran from a marsh at what is now Aotea Square down Queen Street to the Waitematā Harbour. It was infamous for obnoxious odours, particularly during the hot summer months, as it was little more than an open sewer.

The western side of the Ligar Canal was occupied by grog shops, dingy hotels and shanties.

1870s

Auckland grew dramatically in the early 1870s, with the population of the Queen Street area and the surrounding ridges reaching 15,000 by the middle of the decade. Ponsonby, Karangahape Road and Parnell all experienced strong population growth as a property boom gained momentum.

First it was commercial property – including warehouses, shops and offices – then residential land for subdivision and quick resale.

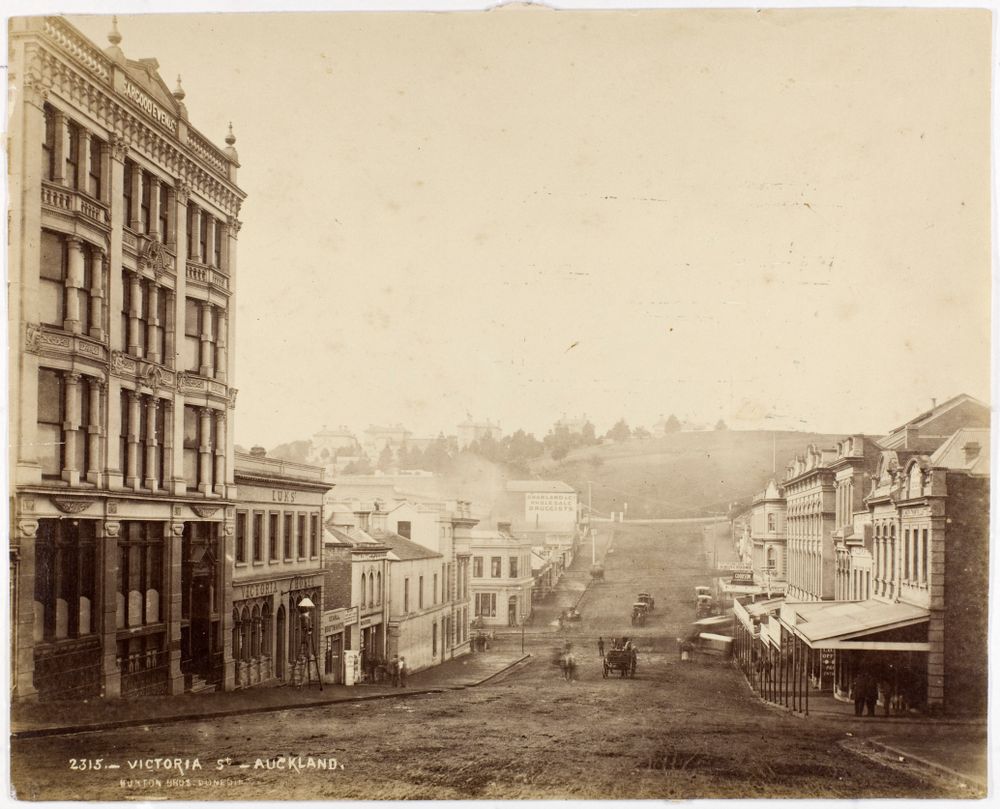

In the 1870s, after the Ligar Canal was bricked in and covered over, Queen Street property values began to surge. Old shanties were knocked down and replaced by three- and four-storey brick and concrete buildings, while commercial premises spread into Lorne, Wyndham, Victoria and Durham Streets.

According to the New Zealand Herald, some early settlers made huge windfall gains by subdividing and selling former residential allotments as sites for commercial buildings.

The boom coincided with the creation of new banks, including the Bank of New Zealand in 1861, the expansion of credit by existing banks and an inflow of capital from the United Kingdom.

According to Russell Stone, “The highly speculative character that both the real-estate and company booms developed in Auckland between 1881 and 1884 showed them to have a common parentage in cheap credit and a get-rich-quick mood.”

Auckland's Victoria Street in the 1880s. Photo: Burton Bros Studio.

Auckland's Victoria Street in the 1880s. Photo: Burton Bros Studio.

Stock Exchange

The Auckland stock market also experienced boom conditions in the early 1880s, and between early 1882 and mid-1883, Auckland sharebrokers floated 62 new companies. These included all forms of transport (railways, trams, ferries), local industry (rope, iron, steel, brick and tile), sugar refining, orchards, tobacco and land.

House building started in Birkenhead and Devonport as the newly listed ferry companies offered regular services across the harbour.

1880s

Inner Auckland was substantially rebuilt in the early 1880s, and the Customhouse and Auckland Art Gallery still remain from that period. A huge number of hotels were constructed, some of which are also still standing, a flour mill was built in Shortland Street and a shoe manufacturer opened up in Hobson Street.

The urban expansion was strongly influenced by transport, particularly the harbour ferries and the Auckland-Onehunga and Newmarket-Henderson rail connections. This encouraged the well-to-do to escape the narrow lanes, tiny allotments and tenements of the old city and move to the open spaces of Newmarket, Remuera and St Heliers.

Investors formed syndicates that purchased farmland and then “leaked” the news of their fantastic property to the daily press. Shortly afterwards, these syndicates placed big ads in the newspapers extolling the “unrivalled natural advantages” and other great features of their sites.

Auctions were packed but, more often than not, it was speculators buying sections from syndicates that had been established by another group of speculators. Buyers were encouraged by dramatic banners, including one that stated, “LAND IS THE BEST AND SAFEST INVESTMENT”.

Property crash

The Auckland property market collapsed in mid-1885, mainly because it had been dominated by speculators who had been fuelled by excessive credit, and there was far more supply than demand.

Auctions became sparsely attended, house-building activity declined dramatically, companies supplying building materials experienced a huge drop in demand, and highly leveraged speculators were crushed.

In July 1888, the Herald reported that “the sudden collapse in the value of property proved a fruitful source of financial ruin to many”. That was a particularly bleak year as investors, who had made a fortune in the early part of the decade, went bankrupt after their land holdings became worth far less than their borrowings.

It is difficult to know how far urban land prices fell after 1885 as there was no Real Estate Institute of New Zealand, CoreLogic or OneRoof statistics in those days and auction prices were regularly manipulated to give the impression that they were holding up. However, there is evidence to suggest that Auckland residential land prices declined by as much as 50% after the 1885 crash.

Auckland quickly followed the rest of New Zealand into a deep economic depression that lasted until 1895.

Obviously, conditions are totally different today and there is no indication that the Auckland residential property market will collapse.

However, borrowers and lenders should always be aware that property markets are not immune to major corrections, even in New Zealand.

Highly leveraged borrowers lost their shirts after the Auckland property market collapsed in 1885 and the Bank of New Zealand, a major lender, had to be bailed out by shareholders and the government in 1895. Nearly 100 years later, the BNZ had to be bailed out again because it had too much exposure to high-risk borrowers.

Memories can fade fast, and become far too selective and positive, particularly when interest rates are low and prices are rising rapidly.

Disclosure of interests: Brian Gaynor is a non-executive director of Content Limited, the publisher of BusinessDesk, and of Milford Asset Management.

[email protected]