With public service pay restraint in place, the gap between public and private sector chief executives is expected to increase.

The latest ‘Pay at the Top’ report by remuneration consultants Strategic Pay shows, of 585 chief executives surveyed, median fixed pay increased by 2.1% between 2020 and 2021.

In the report foreword, Strategic Pay managing director Cathy Hendry said there has been low movement in total remuneration levels for senior leaders in the past year, suggesting incentive payments have been greatly reduced.

“However, we are seeing projections for increases over the next 12 months bouncing back to pre-pandemic levels, suggesting this slowing of wage movement is going to be short-lived.”

Border closures have created a skills shortage, meaning there is increased competition for senior executives. Combined with high inflation and low unemployment, Strategic Pay expects increased wage pressure, particularly at the executive and senior management levels.

“If the government continues to mandate wage restraint in the public sector we could also see a widening gap between private and public sector rates,” Hendry said.

In an interview with BusinessDesk, Hendry said average private sector remuneration for the chief executives surveyed by Strategic Pay was $672,600. However, this included a large spread due to vastly different company sizes.

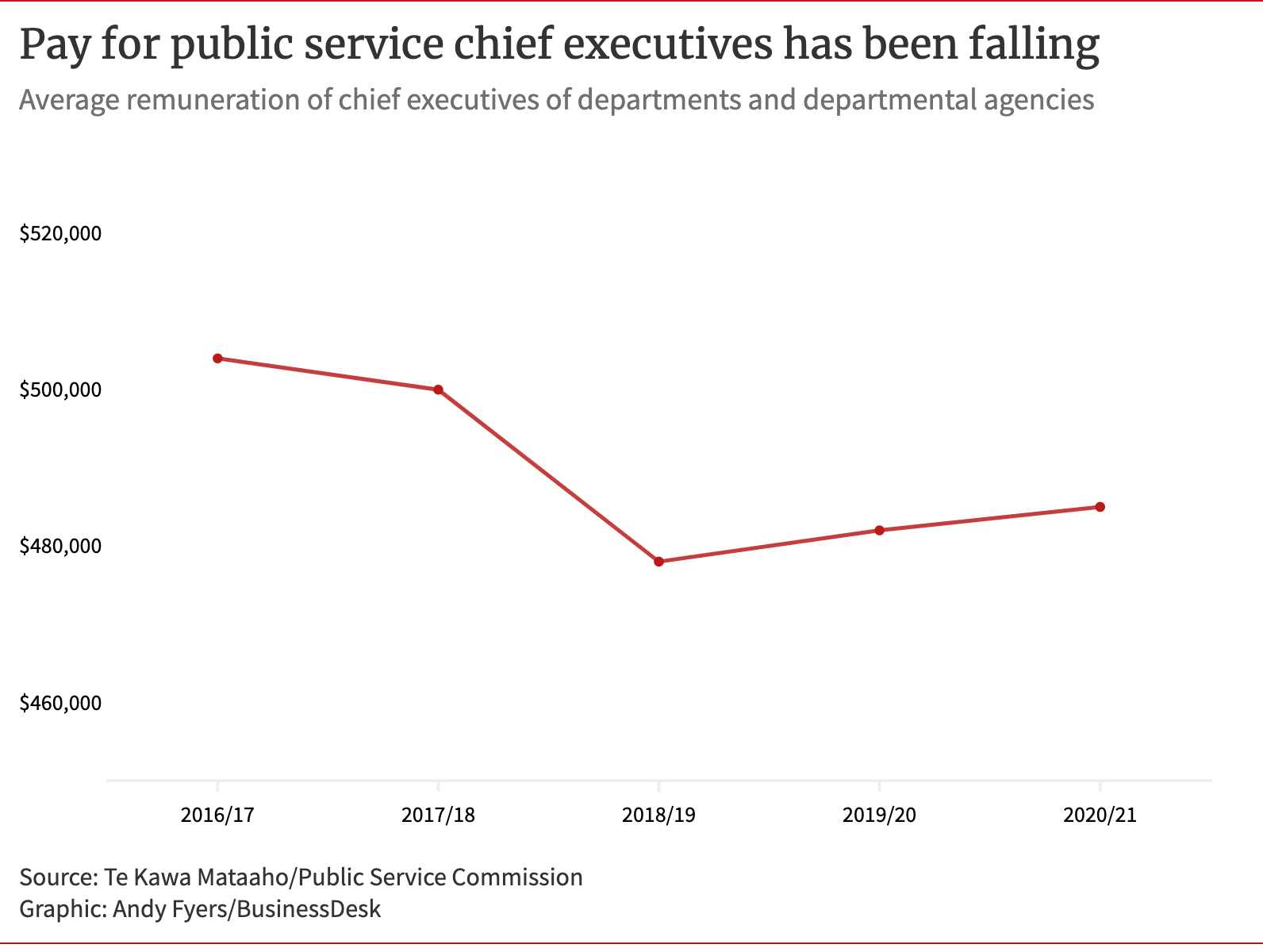

According to new data released by the Public Service Commission, the average total remuneration for public service chief executives was $485,000 in 2020/21, up less than 1% on the previous year and down 4% on $504,000 in 2016/17.

The commission has had pay restraint guidance in place for public service departments since last year due to covid-19, with a particular focus on public servants earning more than $100,000.

According to Strategic Pay, forecast 2022 base salary movement for chief executives in the private sector was 2.4% compared to 1.5% in the public sector.

Hendry said the pay gap between public and private sector chief executives meant the public service was largely limited to recruiting from within its own ranks.

Pay restraint guidance had the unintended outcome of putting new hires in higher salary bands, she said, as any subsequent pay rises would be limited.

The new data from the commission appears to back this up. While the average salary across the public service increased by 3.7% (less than the private sector), the figures show a 21% jump in the number of public servants earning more than $100,000.

Hendry said pay restraint didn’t appear to be sustainable.

“It’s just not going to stick, is it? When you look at inflation, wage pressure, unemployment, the numbers are all suggesting wage increases.”

The latest Strategic Pay report also found staggeringly high turnover among listed companies, with 22% of all companies included in the research reporting a new chief executive or managing director in the past year.

Hendry wasn’t certain why this had happened but said it could have something to do with people reconsidering their options due to the pandemic or organisations needing different skill sets at the top to adapt to the covid-19 environment.

Different labour markets

In an Official Information Act (OIA) response to BusinessDesk, the commission said setting public service chief executive pay was a balance between needing to maintain public trust and confidence in the sector, and the need to attract and retain leaders motivated by a spirit of service.

“There are a range of reasons why public sector remuneration, particularly at the senior executive level, is and needs to be lower than the private sector.”

Victoria University of Wellington academic Dr Geoff Plimmer, a senior lecturer at the school of management, described the public and private sectors as segmented labour markets.

“You’ve occasionally had private sector people coming into the public sector, but that hasn’t always worked out that well,” he said.

“I would say the skills involved aren’t always comparable.”

Public service chief executives operated in a highly exposed political environment, with more rules and more complicated public expectations, he said.

“I don’t think people who have their careers in the public service are that motivated by high paychecks and driving the fastest car and so on."

The real issue facing the public service, Plimmer believed, was developing a deep talent pool to ensure a pipeline of potential future chief executives.

“They have put a real effort into developing leadership frameworks and developing leaders in the last seven or eight years rather than just buying talent on the spot market, as the former State Services Commissioner put it.”

However, Plimmer felt the public service could better achieve this by broadening its approach to leadership development, as opposed to focusing on a select group of people who caught the eye of senior management.