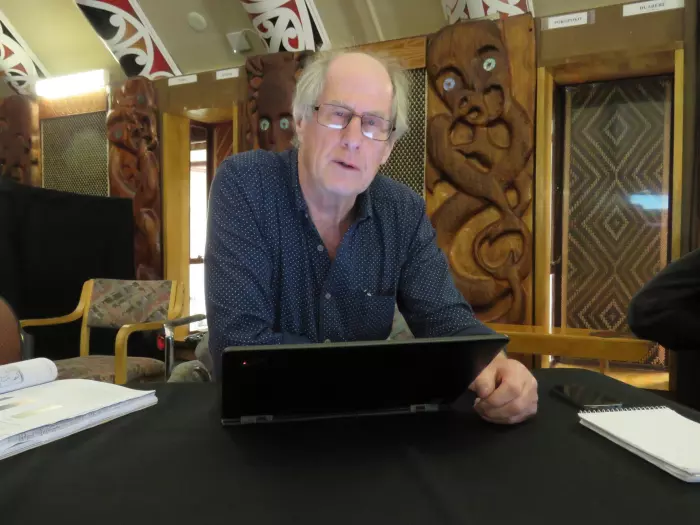

It’s an interesting time to be one of New Zealand’s top property journalists, but media legend Bob Dey has given it all up.

The 73-year-old news veteran put down his pen seven months ago after publishing the well-read Bob Dey Property Report for over 20 years. He has wound down his media companies, shut his website, and has no plans to get back into the writing business as the government launches the biggest shake-up of the real estate sector in decades.

Living a life of retirement doesn’t stop Dey from aiming a dig at policymakers, though.

“Because I’m retired, I didn’t have to read it all,” he says of the sweeping reforms announced last month. “But stopping people from deducting interest [from rental income] is normalising differences in treatment, which you shouldn’t do ... It’s not smart.”

“Overall, this government is performing a lot more poorly than it set out to,” he adds. “They have promised advances and improvements but haven’t had the gumption to set it all up.”

Not that he has much kinder words for the opposition.

“National is a dreadful party to have as a government because they cheat on you. That’s fairly normal right-wing governance.”

The seasoned journalist hasn’t lost his sharp tongue after 55 years in the profession, including spells at ABC in Australia, The Dominion, The Sunday Star-Times, The New Zealand Herald, and NBR, where he wrote a popular liquidation column, often covering property deals gone sour.

As a critic of the Labour government’s housing reforms, how would Dey fix the nation’s dire housing crisis then?

He argues the country needs to “return to having a far smaller net immigration target”.

“There’s a lack of construction capacity to match the level of arrivals,” he says.

“Previous governments have created this problem deliberately. This government has the time to correct the mistake but hasn’t done anything. You can build the population, but you have to plan for it.”

After informing an army of email subscribers about property for decades, Dey is uncertain about the future of the domestic print media as the Silicon Valley tech giants eat away at advertising revenue.

“Newspaper titles will probably have a place, but paper versions might not,” he predicts.

Dey believes standards have declined across the newspaper industry in recent decades, with sub-editors sacrificed and sacked by top papers to save costs.

He bemoans the “illiteracy” sneaking into copy, even at the world’s most prestigious titles.

“It’s very hard to read a story anywhere these days where you don’t fall foul of illiteracy, whether it’s the New York Times or Washington Post. The writing can be incomprehensible and make you want to give up.”

“You no longer have a second pair of eyes on stories, so you have mistakes. The sentences are topsy turvy,” he adds. “You have to work hard to understand the stories.”

According to Dey, this decline in quality could hurt the profession’s future.

“I’m astonished that there are stories on page one of the New York Times with errors,” he adds. “If you buy a book, you don’t expect that nonsense. The same applies for newspapers.”

However, he sympathises with modern journalists “being worked too hard” in the 24/7 digital age. “People haven’t got the time to check. But these kinds of shortcuts will tell,” he adds.

Dey believes journalism is “surviving, not thriving” and wonders whether publications like the Herald have picked the right strategy in putting up a paywall.

“Credit to Stuff for not doing that,” he says. “But finding revenue streams from advertising is hard, as I found [with the newsletter]. With the Herald charging, I’m not sure. I go through about 20-30 news sites a day. I’m not going to subscribe to 20 or 30 websites.”

While he is critical of much of today’s news coverage, Dey believes strong local titles with a good handle on community issues will continue to serve a purpose. He also supports quality papers taking on more in-depth investigative coverage.

“I like some of the things the Dominion is doing under the new ownership, expanding on historical stuff, and developing deeper stories. That kind of material is vital,” he says.

As an avid news junkie, he wonders how the industry will fare in the coming decades, “as people think everything on the internet is free”.

“It’ll be very difficult for newspapers if they expect people to pay for it,” he predicts.

“After making it free, how do you then go and try to charge money? People like me will say they don’t want to pay, or they will get their news from TV. So the future is therefore grim for the news profession, and we become steadily worse-informed.”

As Dey enjoys a carefree retirement in the Whangaparāoa Peninsula, New Zealand’s vulnerable news media is left to deal with the problems of the future and the question of how to thrive, rather than just survive, in the digital age.