This article has been republished. It was first published in September 2020.

As a new generation of land is converted from farming to carbon-farm tree plantations, former NZ Forest Products Kinleith mill manager Ashley Wilson looks at what and who brought down the once-mighty business.

The 1980s were incredible for New Zealand, politically and economically. At the start of the decade, I was working for the largest company in the country, NZ Forest Products, as its man in Wellington, keeping finance companies, investment analysts, the Government and the Opposition informed of its activities and plans.

By the end of the decade, Forest Products no longer existed. To understand what went wrong, it pays first to know something of the company’s history.

NZ Forest Products was established in 1936 to exploit the huge forests of pinus radiata sown on the Central Plateau of the North Island up to and during the Great Depression. Under entrepreneur David Henry, sawmills and the wallboard mill in Penrose, Auckland, were established, followed in 1953 by the start of pulp- and paper-making operations at Kinleith in the South Waikato.

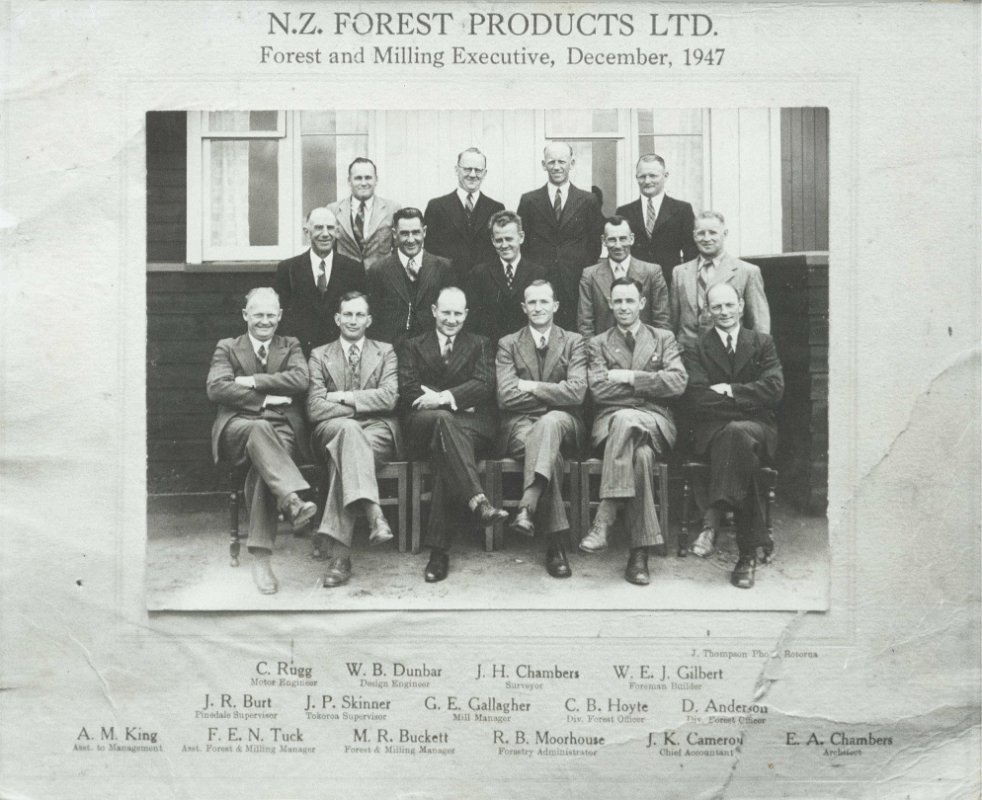

The 1947 executive team. All photos courtesy of Bill Machen and Arthur Hiscock

The 1947 executive team. All photos courtesy of Bill Machen and Arthur Hiscock

Forest Products lost its status as New Zealand’s largest company by market capitalisation in 1981, when Fletcher Holdings and Challenge Corporation merged to form Fletcher Challenge.

That decade was characterised by a number of company bites of other enterprises, and takeover offers. Some examples:

- Fletcher made a grab for Carter Holt

- Caxton tried to buy UEB

- Goodman Fielder bid for Wattie’s

- Wattie’s countered with a bid for Goodman Fielder

- Forest Products formed strong links with Australian paper company APM, now AMCOR.

- Forest Products took 40 percent of UEB

- Alex Harvey Industries bought into Carter Holt to form Carter Holt Harvey.

- Fletcher Challenge was prepared to spend $1.5 billion to take over Forest Products.

NZ Forest Products chairman and managing director, David Henry speaking at the Kinleith mill opening, 1954.

NZ Forest Products chairman and managing director, David Henry speaking at the Kinleith mill opening, 1954.

There was a good reason for companies to take aim at Forest Products. At that time, we had more than 150,000 hectares of planted forests. In our balance sheet, these were valued at cost. Our accountants argued that since a forest could be destroyed by disease or fire, this was a conservative position to take. However, there had never been a serious fire or threat of disease, and one analyst suggested the then share value of $4.42 could really be as high as $8.

Forest Products was doing well. We were a major producer for the local market as well as being an exporter, so we were getting export incentives. We made 250 grades of paper because we were protected by import licensing. Customers in New Zealand had to use our products; once a year, we told them the new price they would have to pay!

But farmers were complaining to the government that industry was getting a financial advantage over them and feared good pastoral land could be lost to forestry. As well, New Zealand’s export incentive scheme was under fire from GATT, the Geneva-based multilateral General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

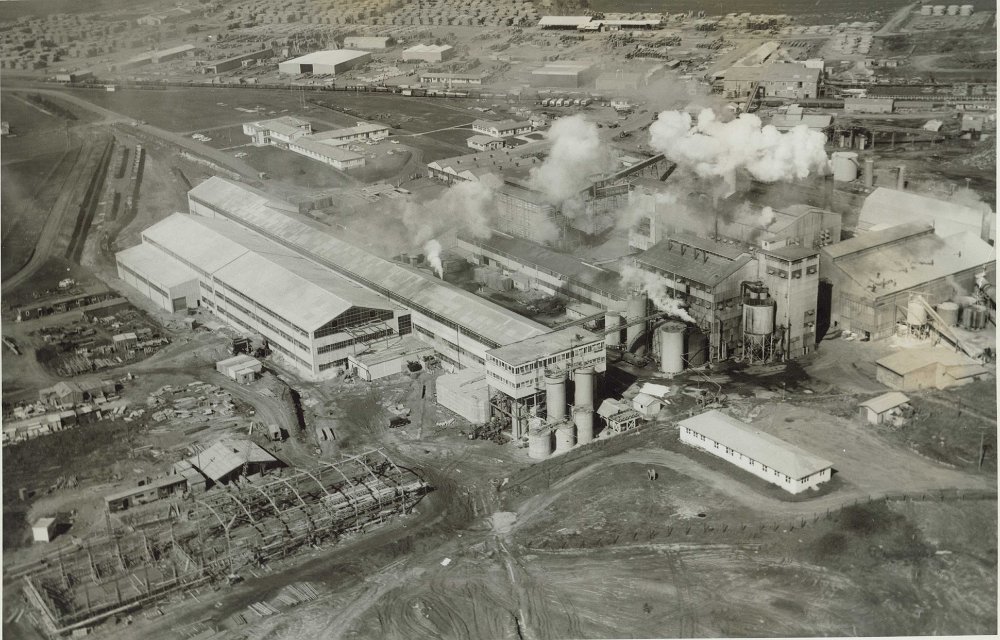

An aerial view of Kinleith mill in 1959.

An aerial view of Kinleith mill in 1959.

Everything changed in 1984. At that time, I was manager of the Kinleith mill, which employed more than 3300 people. It was election year, and in keeping with our tradition, we invited both the Prime Minister, Rob Muldoon, and the Leader of the Opposition, David Lange, to speak at lunchtime meetings. Muldoon was the first to visit. He gave an outstanding address, and despite the workers being mainly Labour supporters, there was no booing.

Lange, when he visited, received an enthusiastic reception, and went on to score an emphatic victory at the polls. But his new government was immediately faced with a currency crisis, and the incoming Minister of Finance, Roger Douglas, floated the dollar, phased out export incentives and moved to sell state-owned enterprises.

Overnight, New Zealand ceased to be a closed shop with import controls and government intervention. The period after this was not well managed; as one commentator observed: “The newly unfettered business environment created by the deregulation of the financial sector left New Zealand an easy target for speculators and their agents.”

Rogernomics, as Douglas’s policies were called, failed to deliver the promised higher standard of living. In the decade to 1992, New Zealand’s economy grew by just 4.7 percent, compared to the OECD’s 28.2 percent. Our credit rating dropped, and unemployment rose.

After Labour was re-elected in 1987, Douglas pushed for further reforms. He got the Cabinet, for example, to agree in principle to a flat rate of income tax. But Lange had had enough. He called for a pause, or “a cup of tea”, as it became known, and later sacked Douglas. Ever eloquent, Lange wrote: “It was an unaccustomed addition to the burdens of office to have the finance minister take leave of his senses.”

In the mid-1980s, more than 200 companies were floated, but few were formed to make new products or create new services. Instead, they were intended to take pieces of other companies that were considered undervalued. You will remember some of the predators’ names: Chase Corp, Equiticorp, Renouf.

There was no worse example of this at the time than what happened to Forest Products. When Wattie’s and Goodman Fielder (through a joint venture, Dominion Industries) took a shareholding in our company, they put Bob Gunn of Nelson on our board. Directors told me he set about stirring things up. He argued Forest Products was sitting around for 25 years for a forest to mature, when other firms were making immediate high returns. He called the company a sleeping giant.

Gunn encouraged the board to form Rada Investments in November 1985. It was floated (the largest float in New Zealand at that time) at 60 cents a share to create a $200 million pool, with another $200 million in bank loans. The following year, it created Pro Rada (worth $100 million), which was to concentrate on property opportunities. The share price of Rada rose to 155 cents.

Then, in October 1987, sharemarkets around the world crashed; New Zealand was particularly hard hit because of the speculation that had occurred here. Brierley shares, for example, plunged from $5.31 to $1.95, Renouf from $3.86 to 42 cents, Chase from $5.01 to 90 cents and Equiticorp from $3.86 to $1.27. There were many business failures, and more than one company leader went to prison.

Writing in January 2001, Brian Gaynor commented that “shareholder confidence in business leaders took a hammering during the horrors of the sharemarket crash in 1987”. He remarked that up till then, New Zealand had respected business leaders such as Henry Kelliher (DB), Jack Newman (Transport Nelson), Russell Pettigrew (Freightways), Robertson Stewart (PDL), Ron Trotter (Challenge Corp) and Roderick Weir (Crown Corp). But prior to the crash, a new generation of business leaders were “granted hero status”. They included Ron Brierley, Allan Hawkins, Bruce Judge, Colin Reynolds and Bob Jones. Respected market commentator Max Gunn (no relation of Bob Gunn) lamented, “It is not my world anymore. New Zealand businessmen have introduced a new morality to the market.”

Rada shares fell progressively until, in 1988, they reached just 9 cents and the company owed nearly $300 million to other firms. Bob Gunn and Rada managing director George Wheeler tried to get a $300 million bailout from Goodman Fielder Wattie but were sensibly refused. They were booed by most attendees at one of their last general meetings.

Sadly, by this time, Rada had a 44 percent shareholding in NZ Forest Products, its parent, so it took that great company down with it. Forest Products was sold to Elders Resources, then to Carter Holt Harvey, then to International Paper, then to Kiwi billionaire Graeme Hart, and what remains is now owned by Oji Fibre Solutions, a Japanese company. Elders, incidentally, tried to get into the Forest Products superannuation scheme but the unions successfully fought them off.

The mill in 1989 showing all six papermills

The mill in 1989 showing all six papermills

A few years ago, I went back to the Kinleith mill. In my day, there were two pulp driers and six paper machines. Now, there was just a big pulp drier and one paper machine. The operation had been rationalised, yes, but the mill was making many more tonnes of product and was more profitable – without export incentives – than when I left in 1987. From a staff of more than 3300, there were just 450, with an additional 280 contractors. You can imagine what a serious impact this had had on the nearby town of Tokoroa.

For all the corporate shenanigans that led to the demise of a once-proud company, there is, for me, one consolation. The mill manager, who started with Forest Products in 1979, was still in charge at Kinleith but there had been huge changes in the intervening years. The mill no longer has control of its wood resource, he told me. One-time owner Rank Group – Graeme Hart’s private investment company sold the majority of the business to Harvard University's endowment fund and most of the rest was bought by a Scandinavian super fund. The forests are now managed by Hancock Forest Management Ltd, a US company with substantial forest holdings in NZ. Now Kinleith is exposed to external influences, especially global wood pricing.

This reliance on external wood, instead of having its own substantial wood supply, is just one of the many radical changes Forest Products has undergone over the past thirty plus years.