GAVIN EVANS: Climate policy favours bans over plans

Worcester Bosch, a UK affiliate of the global appliance maker, earlier this year unveiled a prototype hydrogen-fuelled residential boiler.

Its beauty is that it can run on natural gas today and be switched by a technician to run on hydrogen when that fuel is running through the UK’s 210,000 kilometres of pipelines.

That may be a decade or more away, but about 1.7 million boilers are replaced annually in the UK, where hot water and heating in 28 million homes produce about 14 percent of the country’s emissions.

Bosch is investing in new technology now because the UK has a plan, backed up by more than $1 billion of research, to start displacing gas use in industry and homes with hydrogen.

The UK government may mandate hydrogen-ready boilers by 2025 and it’s not waiting for all that gas to come from renewable sources; to meet its 2050 targets it knows it needs to build a hydrogen industry today.

In contrast, New Zealand’s recent climate policy favours bans over plans.

Successful plans are developed through collaboration, tend to lead to partnerships and investment, and then deliver results.

Bans – not so much.

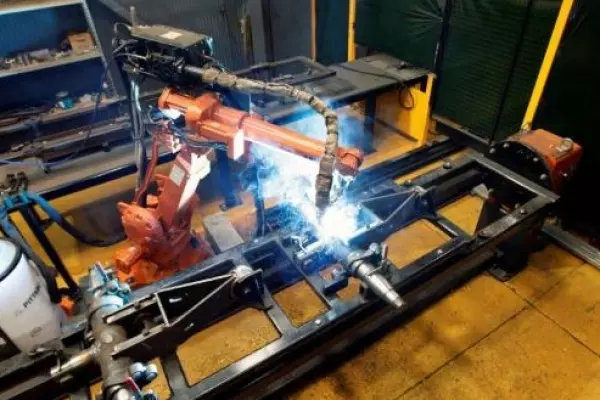

And that’s a problem. While emissions reduction will be a function of broad societal change, it will depend entirely on a lot of clever and expensive engineering to provide us day-to-day emitters with new low-carbon products and services.

And the biggest gains will be made when trucking firms have the confidence to invest in new electric or hydrogen fleets, food processors and manufacturers have confidence to invest in new boilers running on new fuels, and fuel and chemical producers invest in cleaner, more efficient processes.

Because inevitably, reducing emissions requires investment by emitters.

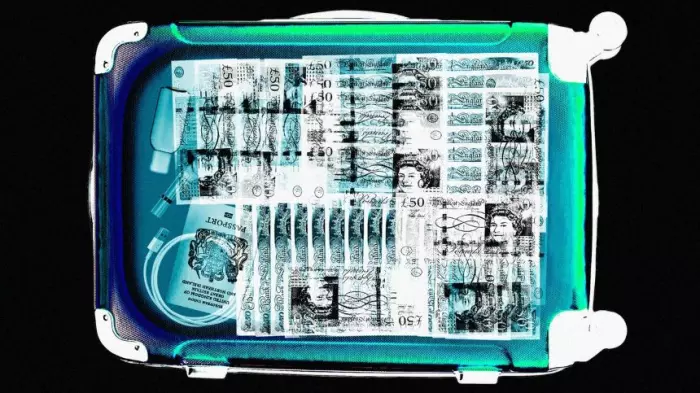

That’s why the government’s latest posturing on climate change – banning default KiwiSaver funds from investing in fossil fuel production – is so disappointing.

For sheer ineffectiveness it beats hanging off the side of a drilling rig in Cook Strait.

Climate Change Minister James Shaw’s claim that fossil fuel firms are the “leading cause of the climate crisis” is dishonest and convenient finger-pointing that does nothing to focus community efforts on things that actually reduce emissions.

It sets up a fake dichotomy with renewables that denies the important role low-emission natural gas will play globally. It also ignores the considerable skills and resources some of those same fossil fuel firms are already deploying on emissions reduction.

Norwegian oil and gas giant Equinor developed the world’s first floating offshore wind farm and is heavily involved in carbon capture and storage projects in Europe and the UK.

BP last month pledged to have methane monitors at all its major processing sites by 2023 and to halve the carbon intensity of its products by 2050 at the latest.

Locally the ill-defined ban is even more problematic, especially if the Green Party succeeds in its bid to require all Crown investment bodies – including ACC and Public Trust – to divest interest in fossil fuel mining and production.

Does it really make sense to discourage investment in Genesis Energy – because of its stake in the Kupe gas field – when it has just underwritten development of the Waipipi wind farm and is in talks on developing the country’s biggest solar farm as part of its strategy to reduce its generation emissions?

How about Refining NZ, which is close to kicking off a $37 million solar project which will reduce emissions by about 18,000 tonnes a year? It is also a key player in plans for a hydrogen hub in Northland.

It wasn’t always this way.

In 2003, the Clark Labour government entered into a 20-year negotiated greenhouse gas agreement with Refining NZ to exempt its plant at Marsden Point from emission charges and encourage investment in cleaner fuels.

Since 2005 the company has invested about $750 million, cutting the carbon intensity of its output by about 20 percent in the past decade.

The company is scheduled to enter the emission trading scheme in 2023 and clearly has more to offer.

But it is worried about long-term gas supplies – the subject of another ban – and a reduction the government has proposed in the protection provided to heavy emitters from competitors not also facing carbon costs.

Businesses – and their customers - are keen to help meet the 2050 net zero target. And the annual energy plans officials have proposed for the country’s 200 biggest energy users show promise.

But they won’t work unless all options are on the table, including natural gas and carbon capture and storage. And they won’t work if we keep allowing long-term investment and planning to be undercut by short-term gesture politics.

Comments