It’s me again. By now, you will have worked out I’ve got a keen interest in public service efficiency and public sector delivery.

I’ve also got strong opinions about calendars and the importance of letting the frontline get on with their jobs.

That’s why I was intrigued to read the Public Service Commissioner’s letter to his chief executives.

Let’s talk about what he said about meetings. Sure, they’re a staple of organisational life, especially in the public service.

But the Public Service Commissioner, correctly, pointed out that the public service has too many meetings.

It struck a chord with me. Not because meetings are inherently bad (though let’s be honest, they often feel like a form of workplace purgatory), but because they’re usually a symptom of a deeper issue: system noise.

System noise is the unwanted variability in decision-making that creeps into organisations, causing confusion, inefficiency, and frustration.

It’s why two people, given the same information, can come to wildly different conclusions. It’s why projects get delayed, priorities get muddled, and project managers and frontline workers – the ones actually delivering services – get pulled into endless discussions about delivery rather than actually doing the delivery.

Authorising noise

The problem isn’t the meetings themselves. It’s the noise that necessitates so many of them. And in the public service, much of that noise originates in the authorising environment.

This is the layer of bureaucracy where decisions are made, unmade, and remade with the enthusiasm of a toddler building (and immediately destroying) a block tower.

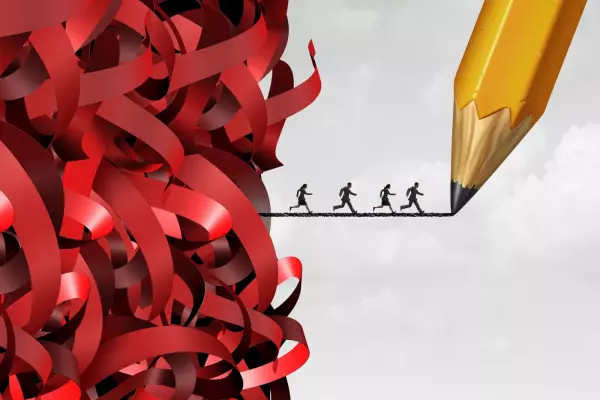

It’s where good ideas go to get tangled in red tape and where frontline public servants are often pulled away from their core work to answer queries, provide updates, or justify decisions.

The authorising environment is, frankly, where a lot of the trouble starts. It’s where the noise gets amplified, decisions are second-guessed, and the focus often shifts from what needs to be done to how it might look.

This environment is necessary, of course – decisions need to be scrutinised, and accountability is important. But when it becomes too noisy, it creates a ripple effect that disrupts the entire system.

Collective responsibility

In theory, the authorising environment is supposed to function as a well-oiled machine, with collective responsibility and collaboration between ministers and senior officials ensuring that decisions are made efficiently and effectively. The idea is that by working together, ministers and officials can balance competing priorities, share the burden of decision-making, and present a united front to the public – and to those who then have to make sense of the decision in order to implement it.

In practice, however, collective responsibility often has the opposite effect. Instead of streamlining decisions, it can create a kind of decision-making paralysis.

When everyone is responsible, no one is truly accountable. Ministers and senior officials become wary of stepping on each other’s toes or contradicting the message, may defer decisions, seek endless consultations, or water down proposals to the point of ineffectiveness.

This dynamic is further complicated by the fact every Cabinet often has competing priorities and constituencies. What’s good for one portfolio may be bad for another, and finding common ground can be a slow and noisy process. The result is a system that’s designed to mitigate risk but often ends up magnifying inefficiency.

Consensus theatre

Here’s the irony: all the meetings are often an attempt to solve the very problem they exacerbate.

They’re meant to clarify what the authorising environment wants and align people and resources around it. But as Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein point out in their book, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, meetings don’t often clarify what the authorising environment wants – they can add to the noise.

Think about it. How often have you sat in a meeting where the loudest voice in the room – or the most senior person – dictates the outcome, regardless of whether it’s the right call? This isn’t decision-making; it’s decision-by-consensus theatre. And it’s a recipe for more noise, not less.

Practical ways to reduce the noise

So, if the answer isn’t meetings, what is? Kahneman, Sibony and Sunstein suggest a concept called decision hygiene – a set of practices designed to clean up the messiness of human judgment.

So here are some concrete examples to aid public service delivery:

- Aggregate independent judgments: Instead of gathering everyone in a room to hash it out, ask individuals to make their decisions independently first. Then, aggregate those judgments. This reduces the influence of groupthink and ensures the loudest voice doesn’t drown out the best idea.

- Define clear scales: Ever been in a meeting where someone says: “This is a high-priority project” and everyone nods, only to realise later that “high-priority” means something different to each person? By defining clear, objective scales for decision-making you can cut down on this kind of noise.

- Use algorithms (wisely): Before you panic about robots taking over, hear me out. Algorithms can help reduce noise by removing the human element from certain decisions. For example, using data-driven tools to allocate resources or assess risk can free up frontline workers to focus on delivery, not head office politics.

- Protect the frontline: The real heroes of the public service are the people on the ground – the teachers, nurses, caseworkers, and others who deliver services daily. They shouldn’t be dragged into head office processes. By reducing noise in the authorising environment, we can let them get on with their jobs. It does mean, however, that one or two back-office people need to be responsible for change and delivery impact. You know the ones, the experienced wise heads who know how to hold the various systems together.

The people side of noise reduction

Reducing noise isn’t just about improving efficiency, it’s also about improving people’s lives. For frontline workers, less noise means more time to focus on what they do best – helping people. For managers and decision-makers, it means less frustration and more clarity. For the public, it means better services are delivered more effectively.

Reducing noise helps create a work environment that’s less stressful, more focused, and more fulfilling. It allows people to do their jobs without unnecessary interference and gives them the tools they need to succeed.

The bigger picture

The Public Service Commissioner is right to call out the meeting overload, but the solution isn’t fewer meetings, it’s better decisions.

By tackling system noise, particularly in the political authorising environment, we can create a public service that’s more efficient, more effective, and less frustrating for everyone involved.