Māori heritage is being routinely desecrated in New Zealand, a Māori land activist believes.

To back up her assertion, Pania Newton points to the high approval rate for permits needed to modify or destroy archaeological sites, the paucity of prosecutions and the dominance of colonial-built heritage on the heritage list maintained by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga (HNZ).

"We're losing so many places that need protecting," she says.

Newton co-founded Save Our Unique Landscape (SOUL) with her cousins to spearhead the campaign to protect land at Ihumātao in South Auckland.

Fletcher Building had planned to build housing on a block of land near Ōtuataua Stonefields, a site of major significance to mana whenua. The land in question was confiscated by the Crown in the 1860s.

Following an occupation by SOUL and the intervention of the Kiingitanga, Fletcher agreed to sell the site to the government, which is now working with various parties to help determine its future.

“The journey we’ve taken through this campaign has really highlighted the flaws in our heritage laws and the process to protect wāhi tapu,” Newton says.

“Heritage New Zealand isn’t doing enough to protect wāhi tapu and other cultural sites of significance to Māori, especially intangible places and areas of significance.”

In an interview with BusinessDesk, HNZ chief executive Andrew Coleman says the agency does value, identify and protect Māori heritage within its mandate. However, true protection comes from district plans.

At Ihumātao, the environment court upheld a decision by HNZ to grant an 'archaeological authority' to Fletcher. Developers need this in order to modify or destroy known or suspected archaeological sites.

Following pressure from Newton and her group, including a well-publicised occupation of the land, HNZ also reviewed the heritage status of the listed Ōtuataua Stonefields area. It extended the site to cover the disputed land and upgraded its listing on the Rārangi Kōrero New Zealand Heritage List to category 1 – the highest possible, and the same heritage status as the Waitangi Treaty Grounds.

“It was the public attention that forced them to reconsider their decision," Newton says.

"And to be honest – in my heart – I don’t think those people we were working with in Heritage New Zealand actually wanted to support the destruction of this wāhi tapu. But they had to follow the law.”

Regardless, the upgraded heritage status is largely symbolic. The land is still zoned for housing.

Archaeological sites being destroyed

Archaeological sites are defined in law as any place in NZ associated with human activity that occurred before 1900. If people know or suspect that applies to their land, they must apply to HNZ for an archaeological authority. These come with conditions developers have to follow for any finds, including what to do if kōiwi, human remains, are discovered.

Newton says Māori have an umbilical connection to the whenua. Under current settings, she believes wāhi tapu are being routinely destroyed.

“Without those sites to connect to and to speak to, to touch and to feel and to smell, we lose that source of identity, that source of place and belonging.”

Research by Nicola Short, a University of Auckland and heritage consultant, found that between 2014 and 2017 HNZ approved 97% of all archaeological authority applications.

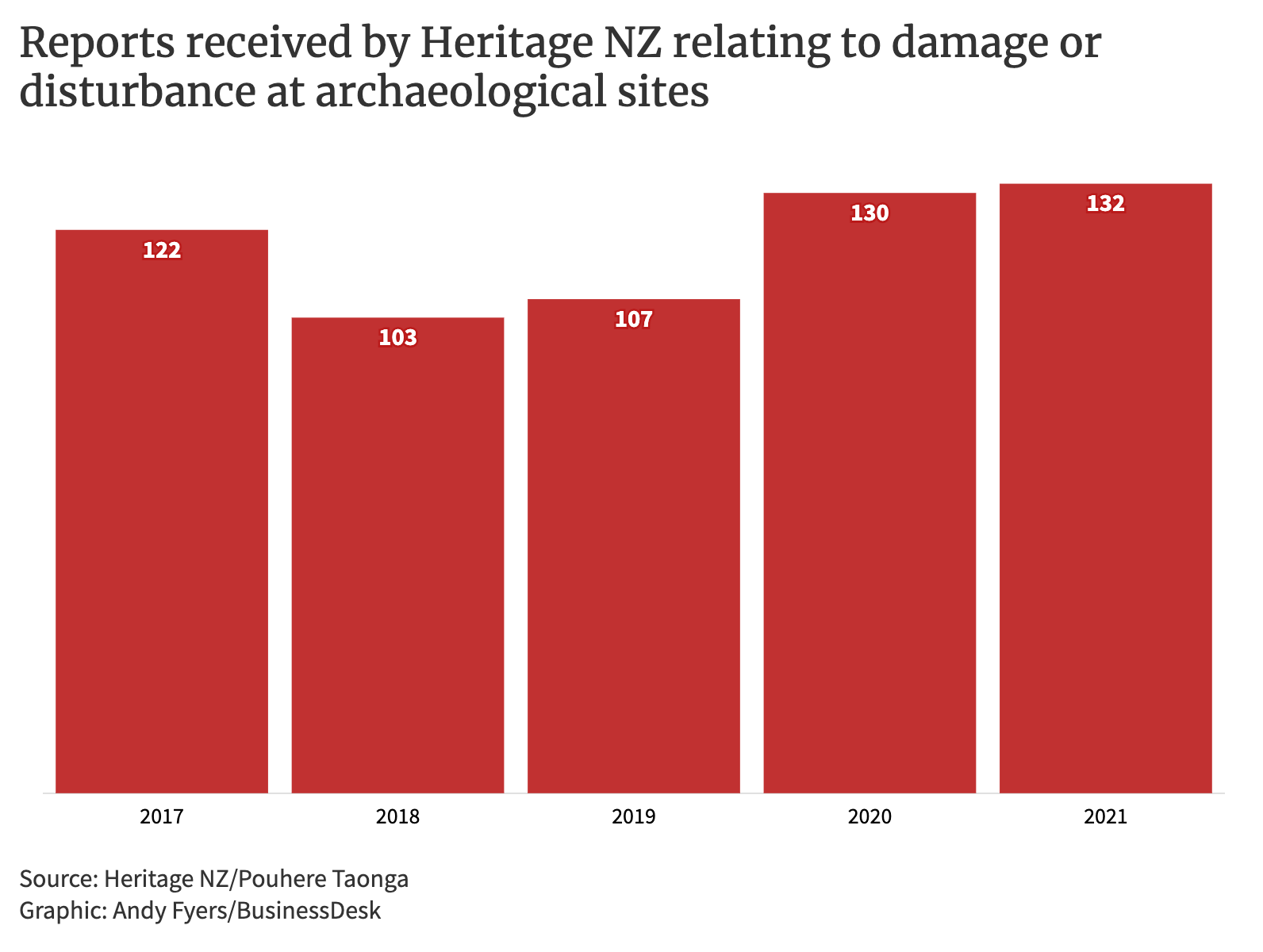

New data uncovered by BusinessDesk using the Official Information Act (OIA) shows HNZ received 594 reports of damage to archaeological sites between July 2016 to June 2021 (not all reports are substantiated).

HNZ has taken just 10 prosecutions since 2015. Two were withdrawn, and four related to damage to midden sites on Motutapu Island. Those four defendants pleaded guilty and were granted diversion.

Newton speculates that many instances of site damage aren't reported to HNZ by developers. She believes the agency isn't adequately resourced to take prosecutions and protect heritage sites.

In its OIA response, HNZ said its annual budget is $170,000.

Coleman later clarified that this was just for external counsel to support prosecutions. HNZ also has three in-house lawyers.

While the number may seem small, ten prosecutions in six years "is still quite a few more than what has been taken in the past, and it’s not a resource issue", Coleman says.

He also encourages people to report archaeological site damage to HNZ.

“If you were a developer and had an authority and you were developing your site, it might be easy just to push the spade back across the top of it.

“But actually, we need to know about those things.”

The list

The Rārangi Kōrero New Zealand Heritage List is divided into five parts:

- historic places (which can be category 1 or 2).

- historic areas.

- wāhi tūpuna (a place important to Māori for its ancestral significance and associated cultural and traditional values).

- wāhi tapu (places sacred to Māori).

- wāhi tapu areas (places with more than one wāhi tapu).

An earlier analysis by Short found that more than 80% of all listings were "European" and less than 10% were explicitly Māori sites. Both she and Newton have called for a review of the list on the grounds it isn’t sufficiently representative.

Newton says the list favours colonial-built heritage over Māori heritage, despite the fact Māori habitation of Aotearoa predates European settlers by hundreds of years.

“It’s all part of the colonial project. It’s about telling the white history of New Zealand so that it legitimises the colonial dominance here in Aotearoa,” she says.

So is the list imbalanced?

“It is if you just look at the numbers, but it’s not if you look at the narrative,” Coleman says. He rejects the need for a review, saying that work was done as part of the reform process that led to the Heritage NZ Pouhere Taonga Act in 2014. This law change created HNZ to replace the former Historic Places Trust.

There are more than 5000 entries on the list. Coleman says any new listing, regardless of what it is, now includes a Māori context.

“You can read a Eurocentric listing around a monument, a memorial or a place but the narrative will describe the original Māori heritage or tangata whenua association of that place.”

He can't make the same assurance for listings prior to 2014.

HNZ doesn’t proactively seek out listings; instead, people nominate places they think should be added to the list. The Māori Heritage Council at HNZ assesses wāhi tapu, wāhi tapu areas and wāhi tūpuna listings.

In an interview with BusinessDesk, Short says the list needs to be more coherent and strategic. It should be a representative sample of quality listings, she says, allowing HNZ to prioritise its limited resources.

As an example, Short says the current list has too many Edwardian villas and too few listings related to pre-European settlements. This is due, she believes, to the Anglo-American approach to heritage taken by NZ in the past.

“When we have this disproportionate evidence of one particular group’s history over another, of course, that’s going to have impacts on not just our sense of place but also how we see ourselves – who we think we are.”

Cultural landscapes

Short says it's too easy to blame HNZ for failing to protect Māori heritage.

There are dedicated people working within the organisation, she says. But a trifecta of constraints – legal shortcomings, resourcing issues and political interference – limits what they can do.

The current act has an emphasis on private property rights, Short believes. There are also no explicit legal protections for "cultural landscapes", a more holistic concept than site-specific heritage that recognises the interplay between the environment and people. She believes the concept better captures Māori notions of heritage.

As it stands, Short says it is difficult for HNZ to decline an archaeological authority. As soon as something is removed from the ground, the integrity of a "cultural landscape" changes and the artifact itself is no longer land-based heritage.

Asked if HNZ could prevent development on private property by declining to approve an authority, Coleman points to the roughly 3% of applications that were denied between 2014 and 2017. The archaeological authorities themselves can impose strict conditions on private land, he says.

Short believes there needs to be a review of the Heritage NZ Pouhere Taonga Act and its interplay with resource management legislation. Under the Resource Management Act (RMA), local authorities have a statutory responsibility to recognise and protect heritage sites from inappropriate development.

Short cites the fact that despite its category 1 listing, the disputed land at Ihumātao is still zoned for housing.

“People think the HNZ list means it’s protected. It doesn’t.”

Any review should consider the role of the local and central government when it comes to heritage protection, with consideration given to national, regional and locally important sites, Short says.

HNZ submitted on the exposure draft of one of the bills to replace the RMA, the National and Built Environments Bill. Coleman says the heritage agency called for better acknowledgment of Māori heritage and cultural landscapes.

Heritage NZ and Māori

Far from highlighting flaws, Coleman says Ihumātao was a good thing for HNZ.

“We went about our core functions uninhibited by everything else that was going on and I understand the determination [by HNZ to upgrade the heritage listing] was quite influential on how things transpired there.”

HNZ is governed by a board and it is also held to account by its Māori Heritage Council, an eight-person panel meant to assist HNZ to take a bicultural view. In 2017, the council released Tapuwae, a document setting out its responsibilities, which include making recommendations to the board on archaeological authorities and recognising and promoting Māori heritage.

Coleman says HNZ identifies and helps conserve Māori heritage, working with iwi, hapu and whānau. It also provides limited protections, but this is mostly achieved through local government.

“We have a limited input into protection because of the RMA and the district and regional planning process, because that’s where true protection comes from.”

On its website, HNZ refers to a range of work undertaken with Māori. The agency employs specialist Māori heritage advisors and provides advisory and on-site services to iwi, hapū and whānau to preserve buildings.

It also administers funding, including 20 grants of up to $250,000 which have been awarded to support the revitalisation of vulnerable mātauranga Māori. Ten grants were for ancestral landscape projects, while the remaining ten were for built heritage.