There's no other New Zealand artist who generates headlines like CF Goldie. From record-setting prices, to robberies, fakes and forgeries, the Goldie market has it all.

Admired by both Māori and Pākehā audiences, his portraits of Māori sitters dating from the first half of the 20th century are arguably New Zealand’s most recognisable artworks.

Charles Frederick Goldie’s personal story wasn’t so happy, and he didn’t enjoy the recognition and reverence during his own lifetime that he has today. Born in 1870 to a well-heeled Auckland family, he showed artistic talent early on.

Although he intended to follow his father into the timber trade, a friend of his dad encouraged him to send the young artist to the Académie Julien art school in Paris at the age of 22.

Although other Antipodean artists attended the académie, Goldie was the only New Zealander to complete the full four-year training in the academic manner of painting, covering basic skills such as figure drawing, tonal modelling and painting historical subject matter.

When he returned to NZ in 1898, Goldie had acquired a technical ability with paint that far outclassed that of his contemporaries.

An exhibition in 1900 of both Māori and Pākehā portraits set Goldie on the path that was to make him famous.

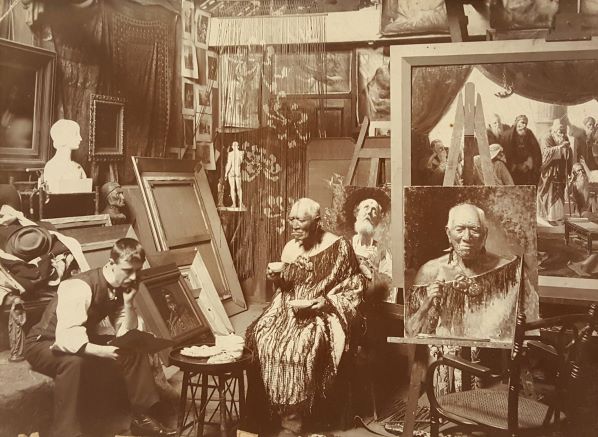

Goldie in his studio with Pātara Te Tuhi.

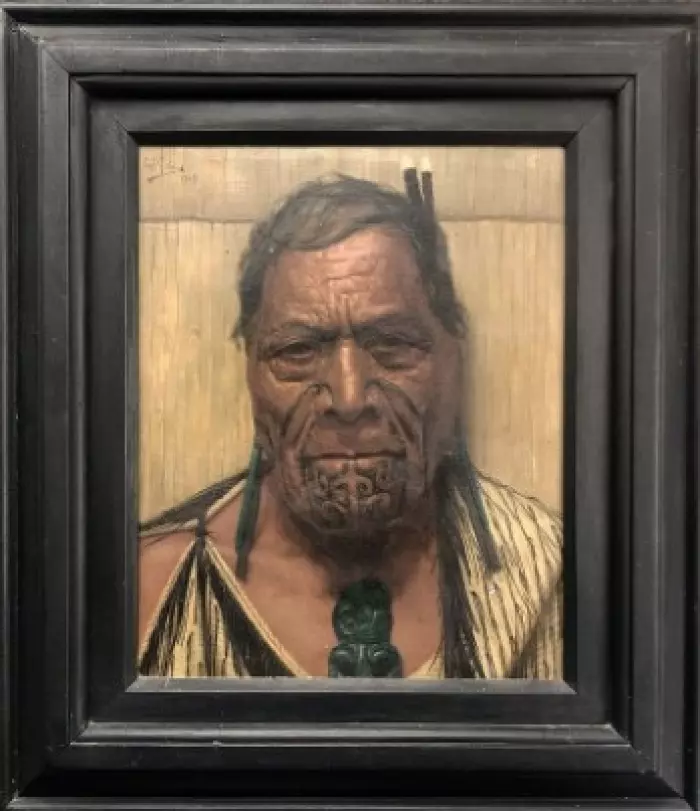

Goldie in his studio with Pātara Te Tuhi.In the first few years of the century, Goldie formed connections with many elderly Māori, who would become his regular sitters. He chose mainly those who wore a moko, and painted them in his Auckland studio, where he provided a feather cloak, clothes, blankets and other props.

Sitters were posed in a way to convey despondent sadness or wistful thinking, supporting Goldie’s belief that the Māori were a dying race.

Although statistics at the time proved otherwise, Goldie was convinced his paintings were a record of these last surviving Māori who had lived through so many changes brought on by colonisation.

Despite his pessimistic view of the future of the race, he enjoyed a good relationship with his sitters. He had learned te reo Māori and could talk with them in their own language. The sitters were paid for their time and many modelled for him several times.

The artistic training from the Académie Julien meant that works produced during this early period, from 1903 to 1915, are some of Goldie’s most skilful and beautifully executed, says dealer John Gow, who has been handling Goldies for 40 years.

Luminous layers

Layers of paint alternate with layers of glaze, giving the best works a luminous glowing quality to the surface. When this is combined with intense attention to detail through the folds of the skin, the lines of the moko and the texture of the fabrics, the result is close to a colour photograph.

By 1911, Goldie’s style seemed dated and out of touch. He was criticised for being too realistic, too photographic and uninventive compared with the looser, more impressionistic style that was popular and being taught in art schools.

In the 1920s, he barely produced anything and was plagued by ill health from alcoholism and lead poisoning from the white lead paint he used.

However, in the 1930s, he returned to his most successful works, painting those original sitters in the same format but using a less defined style. Goldie’s last work was completed in 1941, and he died in 1947.

International Art Centre director Richard Thomson with Hori Pokai – A Sturdy Stubborn Chief.

International Art Centre director Richard Thomson with Hori Pokai – A Sturdy Stubborn Chief.

(Image: International Art Centre)

Analysis of the sales data that underpins the auction market in NZ shows that since Goldie’s death, his work has always been seen as desirable and sought-after. The average price of a Goldie has always sat higher than the average price of the market as a whole, operating as a bubble in its own right.

The market for Goldies has escalated again in the past decade and is in a major growth trajectory. A record price of $1.57m was set in April this year. Five months earlier, a painting exceeded its low estimate by almost a million dollars and sold for $1.42m. Both sales were at the International Art Centre in Parnell, Auckland, which handles most of the Goldies that come to auction.

Director Richard Thomson says he has an extremely active base of buyers for Goldies. Buyers of the artist's work feel very safe in the market, he says, because there has always been demand for his paintings and the sale rate is high – most examples which come up for sale do sell.

There's a finite supply of paintings and a steady stream of works being sold, he says – elements which are crucial to building a market for any artist. Prices have never been higher, but Thomson says there are always new buyers looking to enter the market.

Some clients who have been looking for years have decided to buy now at considerably higher prices than they would have paid a few years ago because the market keeps rising.

Market changes

I believe the wide appeal of Goldie is due to the artist's technical skill. Even buyers with the most limited knowledge of art can appreciate and marvel at his technique.

Goldie repeated subjects and compositions regularly, so it’s fairly easy to track the market changes over the decades. A small painting of one of his favourite sitters, Kapi Kapi, illustrates this.

This small jewel of a work in diminutive size, 24cm x 19cm, shows a snowy-haired woman with a moko draped in a tartan blanket, eyes half closed.

In 1993, the painting was up for auction at Webb’s with an estimate of $30,000 to $40,000 and it realised $40,000. In 2007, it was again at Webb’s with an estimate of $100,000 to $150,000 and sold for $135,000. Finally, it was offered in 2016 at Mossgreen-Webb’s with an estimate of $200,000 to $300,000 and sold for $300,000.

If this work were offered for sale today, it would be expected to sell in the vicinity of $500,000. You could look at other artists such as Colin McCahon or Don Binney over a 30-year timeframe and possibly see a similar price trajectory, but you would find their value would be limited to a particular series of work, such as the McCahon text paintings or a Binney bird painting.

By comparison, because Goldie’s work didn’t dramatically change through his career, the price growth applies across the board, which is really quite unusual.

Māori among buyers

"So, who is the typical Goldie buyer?" I asked Thomson when I interviewed him for this article.

"The perception is that it’s a wealthy Pākehā client, but that’s not always the case," he said.

In fact, Goldie paintings are in most instances revered among Māori because they present such photographic representations of their tupuna (ancestors) and, given the opportunity, some family members of the sitter will buy a painting back.

Most public museums and galleries own Goldies, including Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, which has an extensive and significant collection, but it’s normally a private buyer rather than an institution who is the buyer.

Buyers are also usually NZ residents. To leave the country, a Goldie would need an export licence and it isn’t guaranteed that this would be granted.

The experts agree there are a few characteristics which separate a good Goldie from a great one. Especially sought after are those paintings that depict a male chief wearing a hei-tiki, a huia feather, with a well-defined moko and against a painted background of architectural panels.

John Gow says a chieftainess wrapped in a blanket, with a hei-tiki, and seated in front of a meeting house was an image that was hard to beat.

The works from Goldie's earlier period, 1903-15, tend to be more tightly painted and beautifully executed than the later works, which were looser in style because of his declining health.

Later works worth more

It’s worth mentioning that most of the top prices for Goldies tend to be for the later works, which are larger in scale and therefore carry higher auction estimates.

Works painted in an oval format can be harder to sell and so can works that have had extensive cleaning and restoration. These have a dull flatness to them, where overcleaning has removed glossy layers, so they've lost the sharp clarity of the works in original condition.

Ngāti Whātua pastor Takutai "Doc" Wikiriwhi blesses a Goldie returned after a theft at Auckland Museum in August 2000. (Image: Getty)

Ngāti Whātua pastor Takutai "Doc" Wikiriwhi blesses a Goldie returned after a theft at Auckland Museum in August 2000. (Image: Getty)Finally, provenance is all-important. Look for an unbroken chain of documented ownership, original labels on the reverse, or anything written in Goldie’s distinctive hand – he often titled or annotated works on the frame or stretcher bars, which adds to the originality of the work.

If you're considering buying a Goldie, make sure you go through reputable channels, such as an experienced dealer or one of the major auction houses here or occasionally in Australia or London. That way, you can be assured that provenance and authenticity will be checked.

Karl Sim was a well-known forger of Goldie’s drawings in the 1970s and 1980s and his works fooled many people at the time. These fakes still surface occasionally, as do Māori portraits "in the style of Goldie", which people hope will be attributed to him, or which were perhaps erroneously signed with his name by a later hand.

The lesson here is, if it seems too good to be true, then it probably is. Put it this way: it’s highly unlikely you’ll find an original Goldie on Trade Me.

There are alternatives

If your budget can’t stretch to buying an original by the master himself – and, to be fair, prices now are making it hard for most buyers — it’s worth looking a little down the chain.

Prices have risen substantially for the work of Vera Cummings, a Goldie pupil who painted in his style and even shared the same sitters.

Before 2016, her work regularly sold for under $5000 and now it easily makes between $10,000 and $30,000*.

Chromolithographic prints of Goldie’s original paintings, produced during his lifetime and often in beautifully carved frames, have also become sought after. Until 2016, the prints made between $500 and $1000, but recently they have sold for as much as $15,000.

An interesting anecdote from John Gow speaks volumes about the market both then and now and shows how little things have changed: "I can remember Alan Swinton, the owner of John Leech Galleries from the 1940s to the 1970s, telling me that he sold two major Goldies to one client in the early 1950s. When he took the cheque to the bank, the teller asked if he'd just sold his house."

It's interesting how history repeats. The same question could be asked today when someone "banks" a Goldie deposit.

If this has piqued your interest in Goldies, a couple are coming up for sale in the weeks ahead, at Webb's Auction House and the International Art Centre.

* Since the end of 2021, a number of works have gone unsold, so this could signal that prices may be softening a little.

** All prices quoted are auction hammer price and do not include the buyer's premium of about 20%, which is additional.