In between bites, Albert Cho takes rapid snaps of his sandwich. He keeps eye contact, answering a question even as I see his phone hover into position and a thumb tap the screen. Obviously, getting a good shot comes with the job – the job of being a food influencer.

Cho (aka Eat Lit Food) is arguably our most famous Instagram food influencer. He works at it full-time, having swapped an 8am-5pm job at a magazine this year for a life of partnerships, ambassadorships, sponsorships and collaborations. More than 50,000 followers keep up with his dining habits, and he’s become notorious for his swearword-heavy captions and no-bull attitude, cultivating a sense of authenticity that bluntly cuts through a sea of other, hyper-positive, cookie-cutter food accounts.

The very word ‘influencer’ is loaded, associated with assumptions of entitlement and privilege. “I don’t have a problem with being an influencer, but it really does trigger people,” Cho says. “Anyone can be an influencer. Even if you have 500 followers, you’re an influencer. You’re influencing someone.”

Simply put, influencers promote products or services on social media, which, yes, technically anyone can do. But everyone knows an influencer account when they see one – think glossy photos, a high follower count, and a call to “DM for partnerships” in the bio.

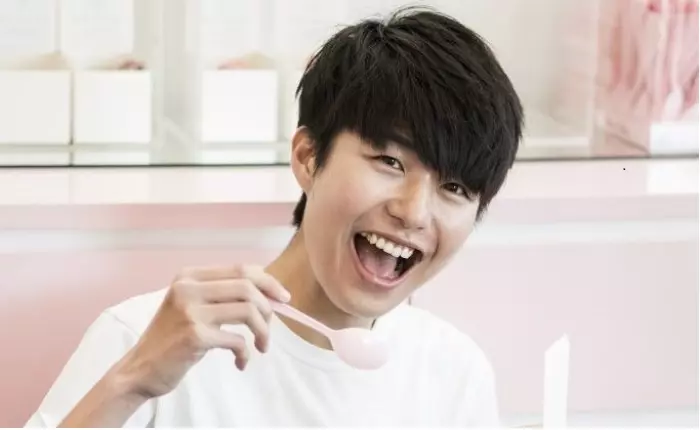

Food influencer Albert Cho. Photo by Samuel Flynn Scott/The Spinoff

Food influencer Albert Cho. Photo by Samuel Flynn Scott/The Spinoff

While we’ve grown familiar with the ways of influencing, demands for transparency have grown louder as the lines have blurred between native content (non-sponsored posts) and advertisements. Cho recalls a time when he posted about a Commercial Bay restaurant, Gochu. “I made it very clear in my Instagram stories that I’m their food ambassador. And I got comments like, ‘Are you telling people you’re getting paid for this?’ It made me look like a phoney. I now have a tag that says #IWouldLikeToDiscloseI’mAnAmbassadorForCommercialBay that I put on all of my Commercial Bay posts. The annoying thing is, I paid for that meal.”

Posting by the rules

Grey areas are usual in this line of work, especially because most influencers do start out by paying for their own meals or products and giving genuine recommendations. It’s only when they begin to gain a following that brands are drawn towards bestowing free gifts and paying for collaborations. These grey areas are where self-employed influencers often run into trouble; without a team to keep things in check, legally required disclosures are regularly forgotten.

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) recently upheld complaints filed against popular social media influencer Simone Anderson, signalling a marked turning point for influencers in New Zealand. The ASA ruled that the hashtag #gifted was not sufficient to indicate that a product had been sent for free, even though no money had changed hands. If there is any commercial arrangement in place that is “controlled directly or indirectly by an advertiser”, the ASA said, then #ad or #sponsored has to be used instead. New guidelines have been drafted to give influencers clearer boundaries to follow. “Making it clear that ads are ads,” the document reads.

Food influencing – as opposed to beauty, health and wellness or fashion influencing – is at its baby stages in New Zealand. Most restaurateurs I spoke to are strongly against gifting free food, let alone paying for social content. Chand Sahrawat, co-owner with chef husband Sid of Auckland restaurants Sidart, Sid at The French Café and Cassia, says although people regularly ask for free meals, it’s completely against their policy to agree. Word of mouth is still king, she says. Sahrawat is not alone: earlier this year, Brian Campbell, owner of Auckland dessert house Miann, reprimanded influencers requesting free food during the alert level 3 lockdown, an especially precarious time for the local hospitality industry. “Please stop for a second and THINK,” he urged them.

Restaurateur Chand Sahrawat. Photo by Josh Griggs

Restaurateur Chand Sahrawat. Photo by Josh Griggs

Follow the crowd

The huge following Cho has is unusual in the New Zealand influencing scene. Most food Instagram accounts are what the industry calls ‘nano’ or ‘micro’ influencers – people who may have only around 1000 to 10,000 followers, but high engagement with their immediate community. For them, it’s more of a hobby than a full-time gig, and contrary to what many people think, they are not generally paid for their posts on top of the free meals they receive. Even giveaways, a mainstay on food accounts now, are usually reviewed for free, in order to grow an account’s following.

Interestingly, Cho gained 5000 followers when he himself was subjected to some unflattering press after penning a negative review of bagel cafe Goodness Gracious. Like they say, all press is good press. It kickstarted his career.

Food influencers are sometimes approached directly, often by local restaurants who don’t receive coverage through mainstream means or serve cuisines aimed at a specific audience – the Chinese community, for example. Sometimes, food bloggers will reach out to eateries independently, a practice that is disparaged, even by Instagrammers themselves. (“That’s what you call a hoe in the industry,” Cho says.) Sometimes, they’re contacted by PR companies who employ social media influencers as part of a marketing strategy for clients; the agencies will usually invite a group of influencers to an exclusive event and provide free food and drinks to the trigger-happy photo snappers in exchange for posts and stories about the restaurant.

The Content Company, an online marketing agency based in Auckland, says these are often contra arrangements (product for payment). A clear brief as to what’s expected is shared – the number of stories, how to tag, what to mention, hashtags, and any rules around archiving posts. These activities are specifically organised for promotional purposes, with the business having some control, so they’re technically an advertisement. As such, they should be tagged #ad, #spon, or have a “paid partnership” tag clearly signalled on the post. “Although some users choose to thank the restaurant, or us as the host,” Tony Collins from the Content Company says, “and in our eyes, that speaks the same truth.”

Tony Collins, owner of The Content Company

Tony Collins, owner of The Content Company

Acknowledging the influencer/restaurant relationship in this manner does require a level of social media literacy that not every follower would have. Thanking the restaurant is common practice even when you’re not receiving free meals – they cooked and served you, after all.

In fact, until recently, many food Instagrammers avoided disclosing their meal was ‘comped’ even if they were invited by the restaurant, leaving it to their followers to pick up on contextual clues to figure it out. Now, hashtags such as #collab or #gifted are often used when restaurants have no editorial control over what is posted and money isn’t exchanged.

Technically, influencers have the freedom to post something negative, if they really want to. Funnily enough, they don’t often want to. “When the meals are free, you’re always obliged to give a positive review, even when you don’t want to,” Cho says. “No matter how many times you tell yourself, ‘No, I’m going to be non-biased’, free food literally tastes better.”

Happy meals

Influencers are also encouraged to post only positive reviews by an unspoken social contract that if they don’t, they won’t be invited back. Cho recalls this happened to him after he spoke honestly (read: badly) about an eatery after attending an event hosted by Zomato, a crowd-sourced food-reviewing platform. The unwritten principle about mutual benefit also applies to free products sent to influencers’ mailboxes – they’ll say nice things about them in their posts or blogs because they want more free goods, simple as that. Interestingly, under the ASA’s new guidelines, this practice is considered influencer content that is advertiser controlled. That raises the question, then – are free meals also ‘advertiser controlled’? Should that #collab tag be an #ad tag?

All of this sure makes it hard for the average joe to sift out the good from the bad, which is why it’s vital that followers have some sort of personal connection to the influencer – that they trust them. Cho has found a way to tie his personal life into his food content, and it’s how he makes his money now, by being an ambassador for dining precincts such as Commercial Bay and Auckland’s Viaduct, as well as promoting beauty and alcohol products. “I found out there’s a way of selling out where you don’t lose your integrity, especially in food,” he says.

Honest reviews are the building block of Cho’s brand, so his captions aren’t always puppies and rainbows, though the impact of his words has started to weigh heavier and heavier as his following grows. “I’m definitely way less scathing than I used to be,” he admits. “I remember writing a bad review for [Auckland’s] SPQR and the comments were like, ‘Oh my God, I cancelled my booking.’ You know, through this job, I’ve met a lot more chefs and restaurateurs, and it made me realise this isn’t a game for them – it’s their livelihood.”

Luna Cafe and Eatery owner Malisa Nguyen

Luna Cafe and Eatery owner Malisa Nguyen

Many eateries have come to value the usefulness of food influencers. “We’re fortunate that within the foodie community, everyone is so genuine, supportive and wanting to help,” says Malisa Nguyen, owner of Luna Cafe and Eatery in central Auckland’s Chancery precinct. After rebranding post-lockdown, Nguyen reached out to food accounts to help publicise the change, communicating the brand makeover to their respective channels. “As much as I want to chat to every customer, it’s hard to have time to do so. But with food influencers, our values and stories can be delivered in the right manner, directly to existing and potential customers.”

Nguyen says she strongly believes that Instagram sways customers’ decisions on where to eat.

While food influencers may have a questionable reputation, they do serve a purpose. They let people who like to eat know what’s shiny and new in the hospitality sector. But given the disillusionment seeping in about them, there’s one piece of advice any budding influencers should keep in mind if they want to grow a following: Know thy hashtag.