Alex van Heeren, who has been in the headlines again because of his acrimonious dispute with his former business partner Michael Kidd, who died in February, was also involved in another major controversy.

This was the privatisation of New Zealand Rail, where he managed to obtain a 9.1% shareholding and sell out for a massive $42 million profit.

How did the Dutch-born van Heeren, who had a South African steel industry background, manage to participate in one of New Zealand’s more lucrative and controversial privatisations?

Why was van Heeren forced to sell the prestigious Huka Lodge near Taupō when he appeared to be extremely wealthy?

Alex van Heeren

Alex van Heeren was born in the Netherlands in March 1947 and moved to South Africa in 1958 as a boy.

In his early 20s, he entered the steel industry but became increasingly concerned about the South African political situation and emigrated to New Zealand in 1981 under our “entrepreneurial scheme”.

He became smitten by Huka Lodge, which had been established in the 1920s by Alan Pye, an Irishman who had identified the stretch of the Waikato River just above the Huka Falls as an excellent spot for fly fishing.

In November 1984, van Heeren set up a company called Worldwide Leisure, which bought Huka Lodge for $1.3m shortly afterwards.

The following year, he was appointed honorary consul for the Netherlands in Auckland, a position he held until 2012. Nevertheless, his home address was usually in Belgium, according to Companies Office records.

New Zealand Rail

In October 1990, the rail business of the old New Zealand Railways Corporation was transferred to New Zealand Rail Ltd, a new limited-liability company. As part of the process the Crown wrote off $1087m of debt and injected $360m of new equity.

The new company was created with no debt because NZ Rail’s board and Fay, Richwhite, its financial adviser, believed it had a better future, and greater investment opportunities, with minimal debt.

In 1992, the Treasury concluded that “there were no apparent public policy reasons for continued Government ownership of NZ Rail”. A year later, NZ Rail was sold to a Fay, Richwhite consortium even though the Treasury was concerned that the merchant banker would have an unfair advantage because it had been the rail operator’s financial adviser.

NZ Rail was sold for $328m. The consortium consisted of:

- Fay, Richwhite 31.8%

- Wisconsin Central 27.3%

- Berkshire Funds 27.3%

- Alex van Heeren 9.1%

- Richwhite family 4.5%.

Wisconsin Central and Berkshire Funds were both US based. Why van Heeren was invited to join the Fay, Richwhite consortium is a mystery. He appeared to have no railway expertise, the deal wasn’t shopped around to domestic investors, and NZ Rail was an attractive investment at the time because of its strong balance sheet.

On September 30, 1993, van Heeren was appointed to the NZ Rail board.

Tranz Rail, the company used to purchase NZ Rail, borrowed $223m to fund the acquisition, with the consortium contributing only $105m of equity.

This was a classic private-equity structure, with the rail company effectively using its balance sheet to borrow money to fund the consortium’s purchase instead of using its strong financial position to invest in rolling stock and other rail assets.

In June 1995, Tranz Rail made a capital repayment of $100m, which reduced the equity contribution of the original investors to just $16m, after taking additional shares issued to management into account.

The $223m of borrowings and $100m capital repayment reduced the average purchase price of the Fay, Richwhite consortium to just under 20 cents per Tranz Rail share.

The following year, Tranz Rail issued 31 million new shares, representing 25% of the company, to the public through an IPO at $6.19 share, more than 30 times higher than the consortium’s average purchase price.

The consortium purchased NZ Rail when it had almost no debt, but the rail operator had term loans well in excess of $300m before the IPO. Most of this debt was used to fund the consortium’s shareholding rather than the purchase of rolling stock and other rail assets.

The original investors – Fay, Richwhite, Wisconsin Central, Richwhite Family, Berkshire Fund and van Heeren – realised profits of $370m, mainly tax free, from the sale of their Tranz Rail shares following its NZX listing.

Van Heeren’s share of this enormous profit was $42m, a great return from a fairly minimal investment.

Huka Lodge

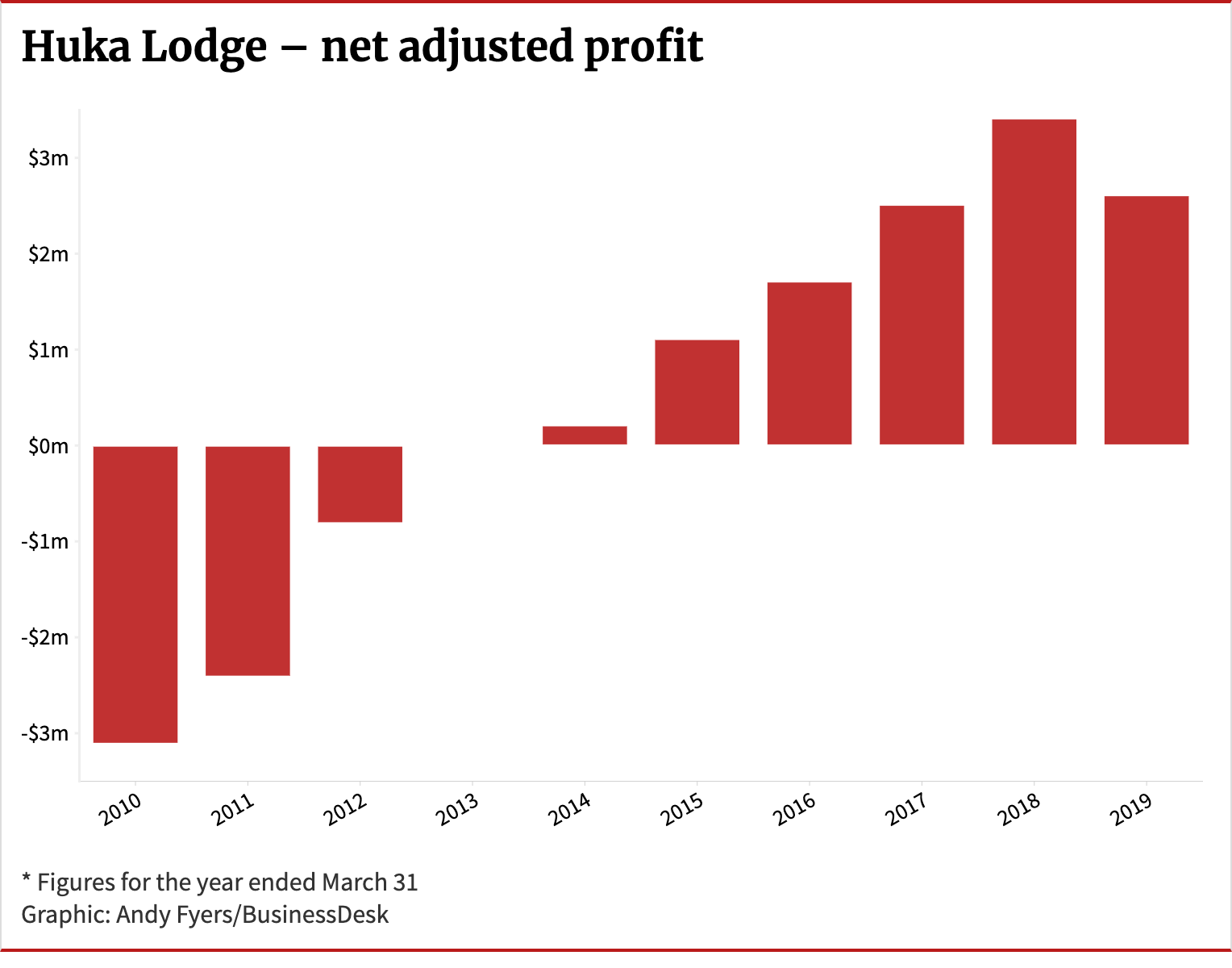

Meanwhile, Huka Lodge, which was owned by van Heeren, turned out to be an extremely successful operation, as illustrated by the following figures.

Revenue doubled over the decade to the end of its 2019 financial year from $8m to $16m, while cost of sales rose by a smaller amount, from $6.4m to $9.9m. Accordingly, the lodge went from an adjusted net loss of $3.1m just over a decade before to an adjusted net profit after tax of $2.6m for the 12 months to March 2019, the last year before it was placed in receivership and before covid.

Kidd v van Heeren

British-born Michael Kidd and van Heeren worked together for a steel-trading company in Johannesburg in the early 1970s.

In 1975, when Kidd was 33 and van Heeren 28, they formed Genan Trading in the Netherlands Antilles, a Caribbean tax haven. The formation of the company was effected in the Netherlands, with Kidd and van Heeren holding 50% each.

Genan generated huge cash surpluses from steel trading, mainly based on Kidd’s trading expertise, while van Heeren looked after the company’s finances.

When van Heeren moved to New Zealand in the early 1980s, Kidd stayed in South Africa even though he had bought a home in Auckland. Kidd moved back to the UK in the late 1980s and the two business partners began to have major disagreements.

In 1991, Kidd and van Heeren finalised an agreement in South Africa to terminate their relationship and divide their business assets.

In 1996, Kidd filed proceedings in New Zealand challenging aspects of this 1991 agreement with van Heeren. These included the following assets: Huka Lodge, development property next to Huka Lodge, shares in Genan Trading, an island retreat on Dolphin Island, Fiji, $30m realised from the sale of 14 million shares in NZX-listed Wellesley Resources in 1987, and gold bars and bearer certificates.

Kidd’s claims didn’t include the Tranz Rail investment, although there was an argument that he would be entitled to his share of the $42m profit realised from this investment if van Heeren had used the $30m proceeds from the Wellesley Resources sale to invest in the rail company.

The legal proceedings have switched back and forth between New Zealand and South Africa over the past 25 years, with Kidd winning most of the arguments. However, he died on February 18 this year before being paid out by van Heeren.

Main arguments

Kidd’s main argument was that Genan Trading, the original partnership in South Africa, had two basic operations: steel trading, which was under Kidd’s stewardship, and the investment of Genan’s profits, which was undertaken by van Heeren.

These assets were to be shared on a 50/50 basis.

In 2015, the New Zealand courts found for Kidd and ordered van Heeren to pay US$25m to him, plus costs.

Van Heeren argued that he couldn’t pay the US$25m because most of his New Zealand assets had been transferred to tax haven-based entities over which he had no control.

Justice John Fogarty took a different view. He wrote in 2015 that transferring assets into small foreign jurisdictions was an attempt to protect the assets “from being the subject of scrutiny and attachment by other jurisdictions. The Netherlands Antilles, the Isle of Man and Liechtenstein all fall within this category.”

The New Zealand courts also upheld Kidd’s caveats over Huka Lodge.

In 2019, the Court of Appeal appointed receivers over the shares of Worldwide Leisure to force the sale of Huka Lodge. The sale was completed this year when Australian-based Baillie Lodges became the new owners of the iconic luxury holiday haven.

But it came too late for Kidd, who in the years before his death had borrowed heavily to take van Heeren through the South African and New Zealand courts.

The New Zealand judgements were particularly critical of van Heeren, with the Court of Appeal judges describing the situation as “fraud by one partner against another, compounded by defiance and delay”.

The judges also wrote that van Heeren’s “arguments that he lacked funds were further falsehoods; what he had done was to put his funds, a significant proportion of which had been obtained by his frauds against Kidd, in places from which extraction was difficult”.

Van Heeren made huge profits from the sale of shares in Wellesley Resources and Tranz Rail, as well as the forced sale of Huka Lodge, while his business partner died before he could enjoy his share of these profits.

Disclosure of interests: Brian Gaynor is a non-executive director of Content Limited, the publisher of BusinessDesk, and of Milford Asset Management.

[email protected]