Bank of New Zealand (BNZ) was expected to drop out of the public spotlight after the Lange government rejected advice from the Treasury to sell the troubled bank to Brierley Investments in December 1988, as told in last week’s retrospective article. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

In early 1989, Allan Hawkins’ Equiticorp Group was in serious trouble because of its massive debt levels and inability to sell its New Zealand Steel and Guinness Peat Group investments.

Hawkins met Equiticorp’s main bankers in Sydney on Wednesday, Jan 18, to deliver the message that his group was solvent, but it needed more money until the NZ Steel sale was completed.

The following day, the bankers informed Hawkins that they weren’t prepared to extend the company’s loan facilities, and later that afternoon, the BNZ refused to honour several Equiticorp cheques, even though they were within the group’s overdraft limit.

On Friday, Jan 20, the Australian Financial Review (AFR) revealed that Fletcher Challenge was no longer interested in purchasing NZ Steel and columnist Chanticleer’s back-page column reported that Equiticorp had liquidity problems and was meeting its bankers.

This wasn’t the first or last time that the AFR published leaked sensitive commercial information.

That was the end of Hawkins’ empire, as Equiticorp’s share price plunged 76% that Friday morning – from 29c to 7c – before the company issued a don’t-sell notice to the NZX.

Two days later, on Sunday afternoon, Jan 22, the New Zealand government appointed statutory managers for the Equiticorp group of companies.

Bad-debt provisioning

BNZ was back in the media headlines as its pre-crash bragging about its lending to Equiticorp was now backfiring.

The media and New Zealand public were joining the dots. It was becoming increasingly clear that the conservative BNZ had been a major lender to the highly leveraged NZX investment and property companies, and these businesses were falling like ninepins.

On Jan 25, the BNZ told the NZX that it had a relationship with Equiticorp and the significance of this would be assessed at its normal monthly meeting of directors the following day. Acting chairman Rob Campbell went on to say: “An announcement will be made by the bank following this meeting.”

However, the BNZ board had a major problem: it didn’t have a sophisticated method for measuring problem loans.

Most well-run international banks had strict criteria for measuring the level of bad debts on a loan-by-loan basis. Bank examiners evaluated each loan with little scope for subjectivity. The level of bad debts was determined by these examiners and, except for matters of policy, directors had almost no involvement in deciding bad-debt provisioning.

The BNZ, which had a historical focus on retail rather than corporate banking, didn’t have a loan examination or reporting and information system that enabled it to accurately evaluate its bad-loan situation. Its bad-debt assessment process was largely discretionary after the Oct 1987 market crash, with the board playing a major role in determining the level of provisioning at the end of a financial period.

Most of its directors had limited banking experience and were essentially plucking figures from thin air, particularly as BNZ management was under-reporting the bank’s bad-loan difficulties in the hope that they would go away.

The huge role played by the BNZ board in determining bad-debt provisioning had an inherent drawback, particularly if two or more directors had different perspectives of share and property markets and the bank’s potential losses in these areas.

These different perceptions resulted in a massive clash between Campbell, who had a trade union background, and fellow director Frank Pearson, who was an experienced investment manager with a front-row seat to the New Zealand excesses of the 1980s.

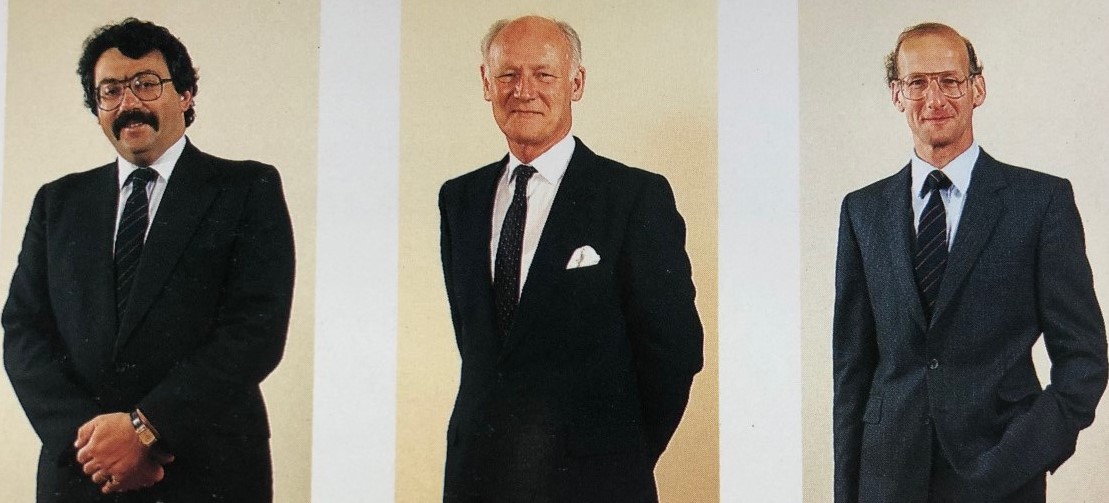

From left: Rob Campbell, Len Bayliss and Frank Pearson.

From left: Rob Campbell, Len Bayliss and Frank Pearson.

Campbell v Caygill & Pearson

On Jan 27, Campbell told the NZX: “It is clear that the continuing effect of the bank’s exposure to the New Zealand economy will require provisioning in the second half of this financial year at a level similar to the first half of the year ($188m and a range of between $370m and $380m for the full year), and this will mean that the bank will return an unsatisfactory result.”

Campbell revealed that Ron Brierley would be returning as chairman, but no specific details of BNZ’s exposure to Equiticorp were provided.

Pearson and fellow BNZ director Susan Lojkine, a Christchurch tax accountant and chair of the Commerce Commission from 1989 to 1994, arranged a meeting with finance minister David Caygill on Feb 2.

They told Caygill that the Jan 27 announcement had understated the bank’s loan problems; the report was too optimistic. Pearson and Lojkine believed that BNZ’s senior management team and Campbell weren’t facing reality – the bank’s bad-debt problems were much more serious than indicated to the NZX. Pearson and Lojkine were backed by two other directors, Len Bayliss, a former BNZ economist, and Peter Leeming, a South Island businessman.

Caygill sided with Pearson and Lojkine because the BNZ’s latest $188m provisioning was below the $400m assessed by both Brierley Investments and National Australia Bank (NAB) during the privatisation process in late 1988.

Caygill was dissatisfied with the leadership provided by the BNZ board and asked Brierley to resign. On Feb 16, the former chairman complied.

On Feb 20, the cabinet agreed to appoint Pearson as the new chairman with Lojkine, rather than Campbell, as the deputy chair. John Anderson, CEO of the National Bank of New Zealand, had been the preferred choice for chair. He had been approached by Caygill and had indicated his acceptance, but the National Bank wouldn’t release him from his three-year non-competing clause.

Former finance minister David Caygill. Photo: New Zealand Magazines.

Former finance minister David Caygill. Photo: New Zealand Magazines.

Campbell’s reaction

Campbell was furious that Pearson and Lojkine had met Caygill on Feb 2 and that they had been promoted to the top two board positions.

The former trade unionist had enjoyed his climb up the corporate ladder. He had built a strong relationship with Ron Brierley and it was widely believed that he would have been appointed BNZ chairman if Brierley Investments’ bid for BNZ at the end of 1988 had been successful.

It was now full-scale war between Campbell and Caygill and between Campbell and Pearson.

Campbell believed the government had overreacted to the bank’s problems. He wanted to remain a director and announced that he would hold an important press conference at 4pm on Wednesday, Feb 22.

That was an incredibly nervous day as there was a run on NZI Bank in the morning, after its parent, NZI Corporation, announced a huge loss, and BNZ appointed receivers to 15 subsidiaries of Richmond Smart, the large Auckland property group.

At noon, Campbell issued an ultimatum to the government in a National Radio interview. His main criticisms were that he no longer saw eye-to-eye with Caygill on the bank and it should remain New Zealand-owned.

Shortly after the interview, Prime Minister David Lange and Caygill met Campbell. They reached a compromise whereby Campbell agreed to cancel his 4pm press conference and not to publicly expand on his views. In return, Lange and Caygill pledged “that the views expressed by Campbell should be looked into”.

Campbell dismissed

The following day, Feb. 23, the BNZ held its first board meeting under Pearson’s leadership. The other directors were Lojkine, Campbell, Bayliss, Leeming, and Pat Morrison, chairman of the New Zealand Wool Board.

Pearson revealed a substantially revised bad-debt provision after the meeting but warned that the figure could be much higher because there were still six weeks to assess before the end of the March 31 financial year.

The feud between Campbell and Pearson broke into the open after the announcement. Campbell was quoted in the New Zealand Herald as saying he found it “amusing rather than credible” that the new chairman was trying to distance himself from the Jan. 27 provisioning announcement.

Pearson was reported as saying: “My trust in Mr Campbell had declined over time,” and he made a comment about “relatively immature hooning around," although he didn’t say who this referred to.

It was obvious that Pearson and Campbell couldn’t sit at the same board table and, on March 13, the government wrote to Campbell saying he was dismissed from the BNZ board.

The following day, the BNZ announced: “David Sadler will join the board. He is an executive director with Fletcher Challenge and the company’s chief financial officer. Sadler will replace Rob Campbell on the board.”

Campbell later became a director and chairman of Ron Brierley’s Guinness Peat Group. This appointment must have been at least partially due to the close relationship the two men developed while on the BNZ board more than two decades earlier.

Campbell’s BNZ experience was fairly traumatic, but he has been a very successful company director in recent years.

Unfortunately, his removal from the BNZ board didn’t resolve its deep-rooted problems.

Its darkest days were yet to come.

You can read Rob Campbell's response to this article here.

Disclosure of interests: Brian Gaynor is a non-executive director of Content Limited, the publisher of BusinessDesk, and of Milford Asset Management.