Chris Amon was sixteen when he started his first proper motor race in his first proper race car in April 1961. It was a 1.5-litre Cooper Climax and he was on the outside of the front row of the grid at the now defunct Levin, a kidney-shaped circuit within a horseracing track, 100 kilometres north of Wellington on New Zealand’s North Island. The pole sitter was Duncan McKenzie in the ex-Jack Brabham 2-litre Cooper. Amon was off like a rabbit and headed McKenzie into the first corner. Then the red flag came out and stopped the race. McKenzie had rolled his Cooper in pursuit and was killed, the only fatality in the circuit’s twenty-year history. Amon decided a spindly Cooper was not for him and traded it for a more substantial Maserati 250F. Juan Manuel Fangio had used one to win the world title in 1954.

In his sixties, Chris took me to see the car at the Southward Car Museum at Paraparaumu: ‘It had so much power,’ he said, his eyes alive with teenage excitement. ‘You couldn’t drive it on brake and steering— it would just plough ahead. You drove it on the throttle. The more you applied the power, the livelier it would get, and you just modulated it.’

Eighteen-year-old Chris drove the 250F to eleventh in the rain-swept 1962 New Zealand Grand Prix on the Ardmore airfield circuit. Stirling Moss won: ‘At one stage I got pretty sideways, and Moss lapped me on the inside and gave me a cheery wave— he thought I was moving out of his way.’

Amon once took pains to play down his background of privilege. Later, he didn’t care so much. It was hard to avoid the fact that as a fifteen-year-old he’d flown in his instructor’s Tiger Moth from his elite boarding college and landed in one of his parents’ paddocks for Sunday lunch. Or that when he attracted the attention of Australian team owner David McKay, his family was able to fund the teenager’s entry into the world of McKay’s Scuderia Veloce. His training car was the Cooper Climax Bruce McLaren had used in 1959 to win his first world championship grand prix at Sebring.

Chris Amon passes the crash of teammate Lorenzo Bandini at the Monaco Grand Prix, 1967. Photo: Getty.

Chris Amon passes the crash of teammate Lorenzo Bandini at the Monaco Grand Prix, 1967. Photo: Getty. In 1963, Reg Parnell, British team owner and star-maker, snatched Amon away to race in Europe. There would be no junior categories, no learning curve, and, for that matter, no living rough. Parnell had struck a deal with an oil company to insert Amon straight into Formula One. He would be paid from the outset and he would be replacing seven-time world motorcycle champion John Surtees, who was moving to Ferrari (where he won the 1964 world title). Amon was just nineteen.

He flew out, alone, in April (his first jet flight), raced Parnell’s Lola-Climax into fifth place in a non-championship event at Goodwood and then travelled to the first round of the 1963 world championship, which was held in Monaco. There could be no more daunting place to debut, but no more an inspiring place either.

Parnell made his other Lola available to veteran and local hero Maurice Trintignant. Neither car was super-fast, not compared to the Lotus of pole sitter Jim Clark. But when Trintignant did a qualifying lap in 1 minute 41.3 seconds, Amon responded with an impressive 1 minute 41.4 seconds. Then the Frenchman blew his engine and Parnell gave him Amon’s car. It was Amon’s first taste of F1 reality.

That year Amon scored two consecutive seventh places— one at the high-speed slipstreaming Reims circuit in the French Grand Prix, the next with a new experimental Coventry Climax engine in the British Grand Prix. It had so much power that, with a momentary loss of concentration at Monza in the Italian Grand Prix, he speared off the track and put himself into hospital with broken ribs.

It got worse: enforced confinement turned to deep-vein thrombosis and a two-month lay-off.

And then worse again: Parnell sent one of the Lolas for Amon to race in the first Tasman Series season. It was there he received the horrible news that 52-year-old Parnell had died from peritonitis, the aftermath of an appendix operation. Twenty-year-old Chris Amon believed his career had ended.

Tim Parnell, Reg’s son, scrambled to save the team and achieved the seemingly impossible. It was a cart and horse dilemma. In order to retain the team’s sponsors, he needed good drivers and in order to secure good drivers, he needed sponsors. He accomplished both. He signed nine-time world motorcycle champion Mike Hailwood, son of a millionaire businessman; aspiring newcomer Peter Revson, part heir to the Revlon fortune; and appointed Amon, perhaps the least well-heeled of the three, as his number one.

The trio shared a first-floor flat in Ditton Road, Surbiton, and became the Ditton Road Flyers, convenors of the best-known party house of the 1960s. ‘It was never as wild as legend has it,’ Amon told me many years later, but he was grinning broadly when he said it. It’s a shame the racing wasn’t as good. Chris was sixteenth in the championship with two points; Mike and Peter were equal nineteenth with one.

That was when Bruce McLaren stepped in. He took on the care of young Amon, arranging sports-car drives for him and offering employment in his burgeoning team. McLaren Formula One was always the promise. In 1966, aged just 22, Chris co-drove with Bruce in the winning Ford GT40 at the Le Mans 24 Hour race.

Bruce McLaren raced his Formula One car for the first time in 1966, but there wasn’t yet one for the impatient Amon. In late ’66 Chris was invited to Maranello to meet Enzo Ferrari. Incredibly, the Commendatore (as Ferrari liked to be known) had chosen the young New Zealander as his next big chance. This was an offer too good to refuse, but his leaving caused a rift with McLaren.

On 7 May 1967, Chris Amon took to the Formula One grid for the first time with Ferrari, at the Monaco Grand Prix. He was number two to five-year Ferrari veteran Lorenzo Bandini; the pair had already won the Daytona 24 Hour and Monza 1000 together in the 4-litre Ferrari P4, and had become good friends. They had driven to Monaco together, after Amon had waited outside a house in Modena where Bandini ‘said goodbye’ to his mistress.

On lap 82, Bandini was chasing Denny Hulme in the Brabham for first place when he hit a concealed bollard above the harbour quay chicane and suffered fatal burns. A media helicopter had fanned the fire. Amon came third.

Bandini and Amon had been due to fly that night to the qualifying sessions for the Indianapolis 500. ‘I had a lot of time on the plane to think about the what-ifs,’ Chris said. He failed to qualify at Indy. ‘I actually felt fear.’

Chris Amon in a Ferrari 312 at the French Grand Prix, 1967. Photo: Getty.

Chris Amon in a Ferrari 312 at the French Grand Prix, 1967. Photo: Getty. Amon was promoted to Ferrari’s number one, and he did well. He made four visits to the podium and was fifth in the championship, a good result in a year in which the Brabhams were dominant. In 1968, Ferrari brought in Belgian Jacky Ickx, two years Amon’s junior and, in his view, his number two. When Chris learned Ickx was being paid substantially more, he fronted Enzo Ferrari to ask why. ‘You never asked for more,’ the Commendatore replied, and upped his salary.

The notorious ‘Amon curse’ that dogged Chris his entire career was on full display in ’68. He outqualified Ickx 8:2, but Ickx brought his Ferrari home fourth in the title and Amon was tenth. ‘I should have won the championship,’ he later lamented. But a stone through his radiator, a broken gearbox when he was comfortably in the lead and a rear-wing collapse at Monza that sent him airborne all worked against him.

Amon became so frustrated he quit Ferrari halfway through the 1969 season. He had just turned 26. ‘It was a damned silly decision,’ he told me many years later. ‘The old man [Enzo Ferrari] wanted me to come back, you know.’ But he never went.

Chris Amon on the winner's podium at the Argentine Grand Prix, 1971. Photo: Getty.

Chris Amon on the winner's podium at the Argentine Grand Prix, 1971. Photo: Getty. From then on, he played musical chairs with team changes: first, the promising start-up British-owned March Formula One (‘a total con,’ he claimed, although he visited the podium three times and finished eighth in the title in 1970); then two years with the French Matra team (he was leading at Monza, when he tried to remove a clear plastic tear-off from his visor, which restores vision, and took off the entire visor instead, blinding himself with a 300 km/h blast of air). He went to another start-up, Tecno, then had a brief two-race interlude with Tyrell that was cut short when his teammate François Cevert was killed in the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen.

Amon toyed with building his own car, the Amon AF101, but raced it only once in Spain and retired it when its brakes failed. He raced twice for BRM, then joined Mo Nunn’s Ensign team for almost two seasons. His results curve was locked in the descendancy.

In 1976, world champion Niki Lauda had his fiery crash at the Nürburgring, his life saved by other drivers who pulled him from the wreck. There was an hour before the race was to resume— time to think. Chris walked up to Mo Nunn and said he was not going to take the restart, bringing his career to a close. In truth, he made a desultory attempt to drive for the Wolf-Williams team in the Canadian Grand Prix at year’s end, but he was involved in a warm-up lap T-bone crash and was classified as a non-starter. His bad luck held true, right to the end.

In 1977, Chris and his wife Tish moved to New Zealand, where they raised three children— Georgina, and twin sons Alex and James— on their large dairy farm. Many people who met him in the second half of his life knew him only as a farmer. Enzo Ferrari, who retained affection for him throughout, said in his memoirs: ‘I wonder if his children believed him when he told them how very near he had been to becoming a motor-racing legend.’

Chris died in 2016 from cancer. He was 73.

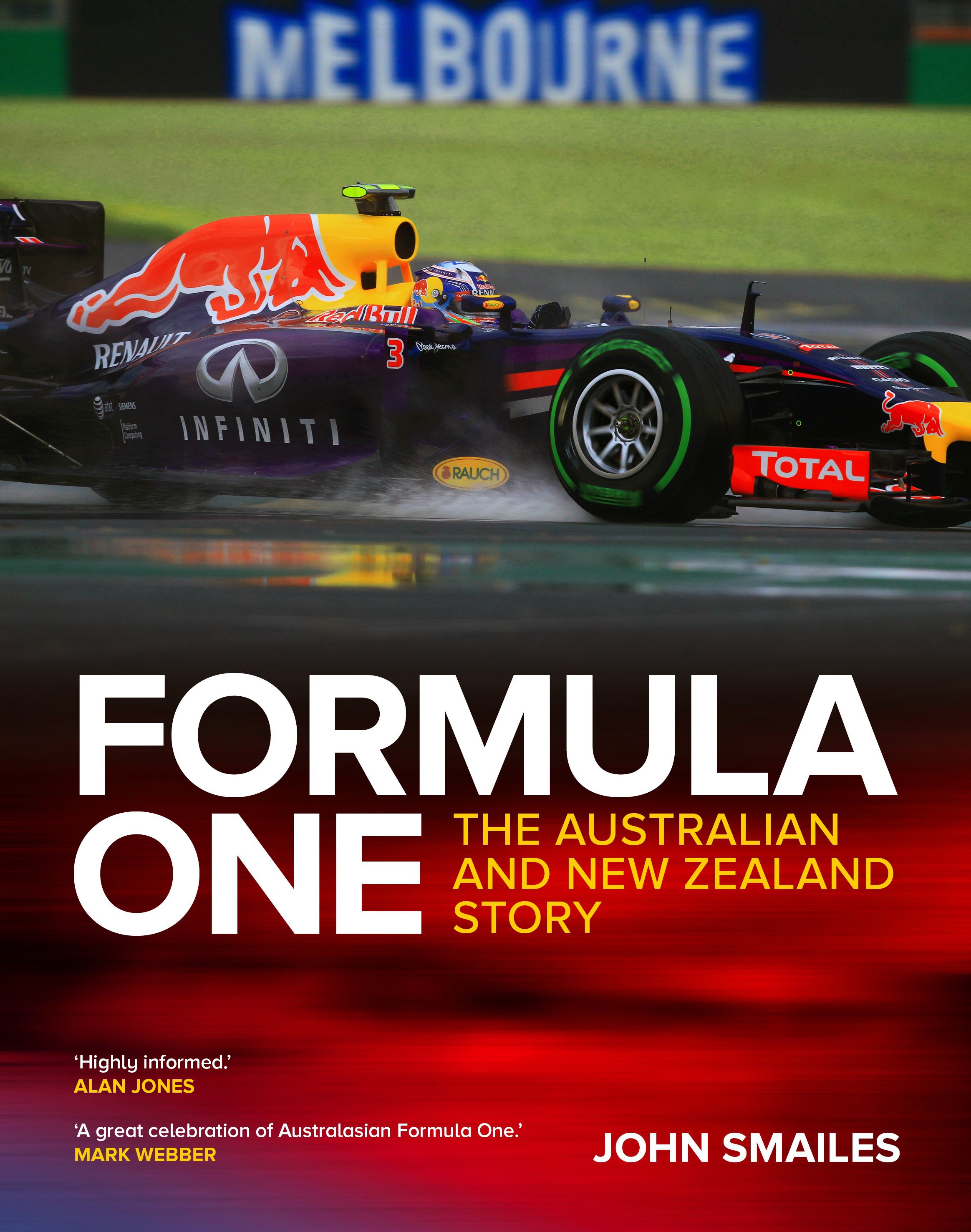

Extracted from Formula One: The Australian and New Zealand Story by John Smailes, published by Allen & Unwin. RRP $45.