By Jason Gale

Most people who suffer from covid-19 fully recover. Millions of others find complete healing to be frustratingly elusive, in what’s often referred to as long covid. Symptoms range from pulmonary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal or neurological problems to cognitive issues such as so-called brain fog.

No single explanation, diagnosis or treatment can be applied to them. Colloquially known as long-haulers, these patients reflect the pandemic’s lasting burden on society and the economy.

What is long covid?

There’s no universally accepted definition yet. According to the World Health Organization, people with what it calls “post-covid-19 condition” have symptoms usually three months after an initial bout of covid that last for at least two months and can’t be explained by an alternative diagnosis.

Symptoms may persist from the acute phase of the illness or appear after – even in a person who displayed no symptoms initially. They may also fluctuate.

Other groups have proposed alternative definitions. The UK’s National Health Service, for example, suggests referring to symptoms that last more than four weeks as “ongoing symptomatic covid” and “post-covid syndrome” if they persist for longer than 12 weeks and can’t be otherwise explained. Another definition may be needed for children.

How often does it occur?

It’s too soon to say. The lack of a standard definition means variables such as what group is being studied and when the data was collected can lead to widely different results. For example:

- A report in May from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found about one in five adults between 18 and 64 years old had a health problem that might be attributable to a previous covid infection.

- A study in July that accounted for pre-infection symptoms in a nationally representative sample of Americans in the first year of the pandemic found that 23% experience at least one symptom that emerges around the time of infection and lasts for more than 12 weeks.

- Another large study published last year, using data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, estimated that about 7% of people had at least one symptom of long covid six months after their infection. The incidence beyond the first 12 weeks of illness was 4.1% among those never hospitalised for covid, 16% among those who were hospitalised, and 23% among patients who were admitted to intensive care. The study also found differences in symptoms by age, race, sex and baseline health status.

Other studies have found the likelihood of long covid is greater among women, the middle-aged and the obese.

What are the post-covid symptoms?

Tiredness and shortness of breath are commonly reported, as well as brain fog – difficulty with concentration or memory.

Other prolonged symptoms include fever, cough, palpitations or pain in the chest, joints, muscles or abdomen.

Neurological symptoms include headaches, disturbed sleep, tingling or numbness, or dizziness.

Digestive issues can cover nausea, diarrhoea or reduced appetite.

Some people report a diminution of the sense of taste or smell, tinnitus, earaches or a sore throat.

Depression or anxiety also can occur.

Do variants carry different long covid risks?

It appears so, though identifying them is complicated by other factors, such as prior covid immunisations and infections.

For example, the UK’s Office for National Statistics found in May that the odds of reporting fatigue, shortness of breath, difficulty concentrating and other persistent symptoms were 50% lower following infections likely caused by the omicron BA.1 variant than those likely caused by the delta strain.

The difference was found only among adults who were double-vaccinated when infected. Among those who’d had three shots, the difference wasn’t statistically significant. Among triple-vaccinated adults, however, the odds of reporting long covid were higher following infection with the omicron BA.2 variant than the BA.1 variant, the analysis found.

Covid patients are often cared for in negative-pressure rooms. (Image: Auckland City Hospital)

Covid patients are often cared for in negative-pressure rooms. (Image: Auckland City Hospital)

What causes it?

Some health problems are well understood, others aren’t. For instance, survivors can experience problems as a result of:

- The direct effect of the virus on organs and tissues.

- The propensity of covid to cause bleeding and clots that can restrict or block blood vessels including in the lung, which can cause a pulmonary embolism.

- Excessive inflammation by the immune system.

- The body’s failure to properly repair injured lungs and other organs, leading to the formation of scar tissue.

- A lack of oxygen in the blood that injures the brain, lungs and other organs.

- An imbalance in the microorganisms inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract.

- Life-saving treatment, including the use of mechanical ventilation, corticosteroids, sedatives and painkillers administered in intensive care.

In a study published in January, scientists at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington in Seattle found the risk of long covid is increased by multiple early factors, including antibodies directed against their own tissues or organs known as autoantibodies, and a resurgence of the Epstein-Barr virus.

Based on what’s been observed with other viral diseases and research so far, other scientists speculate that different biological and genetic factors may be driving symptoms, none of which are mutually exclusive. These may include:

- Chronic, systemic inflammation.

- Immune dysregulation, such as when the body’s immune system overreacts or underreacts to a foreign invader.

- Interactions with the host microbiome, or microorganisms living in the body.

- Problems with the autonomic nervous system.

- The persistence of viral particles or remnants in the body.

Is covid-19 definitely to blame for these symptoms?

Not necessarily. Some symptoms might occur by chance or be triggered by stress or environmental factors such as allergens, while some pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes, might have gone undiagnosed until covid prompted medical attention.

Social restrictions, lockdowns, school and business closures, loss of livelihood, decreases in economic activity, and shifting priorities of governments all have the potential to substantially affect mental health, according to a study that appeared on Oct 8 in the Lancet. It found the pandemic had resulted in an extra 53.2 million cases of major depressive disorder and an extra 76.2 million cases of anxiety disorders globally.

Diagnostic uncertainties have sometimes led to what patients describe as “medical gaslighting” by health professionals who don’t take their complaints seriously, especially if the patient is a woman.

(Image: NZME)

(Image: NZME)

Do vaccines help prevent it?

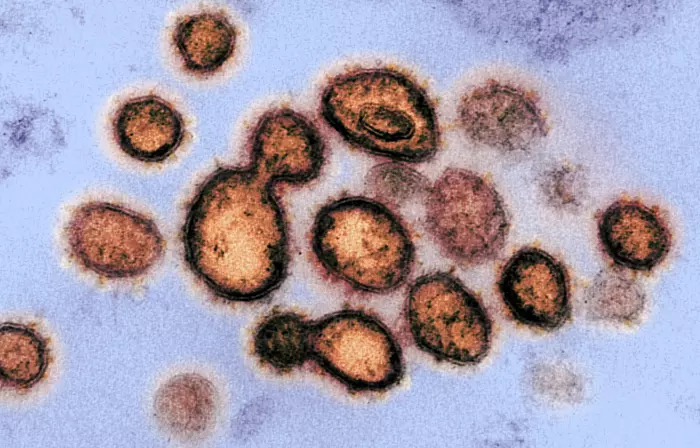

In a way, in that vaccination is the most effective tool to reduce the risk of getting infected in the first place by Sars-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes covid, and it mitigates the likelihood of becoming severely ill.

A UK study found receiving a second dose of a coronavirus vaccine at least two weeks before an infection was associated with a 41% decrease in the odds of self-reported long covid at least 12 weeks later.

Data from Israel supports the finding, though a larger study of some 13 million users of the US Veterans Health Administration system in May found vaccination is associated with only a 15.7% reduction in the risk of long covid.

How serious is it?

Most long covid symptoms don’t seem to be life-threatening, but things like shortness of breath or fatigue can be disabling.

For some covid survivors, the infection may damage vital organs and exacerbate other diseases, the effects of which may not become apparent for months, like a ticking time bomb.

Some of the conditions that may manifest later include cardiac arrest, stroke, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, and chronic kidney disease. Doctors have also noted an uptick in cases of diabetes linked to covid.

A study in February based on the veterans database in the US found the virus may significantly increase a person’s risk of heart disease for at least a year after recovery – even if the person wasn’t hospitalised.

Other studies from the US, UK and Germany showed that people who were hospitalised for covid have an increased risk of being readmitted or dying six to 12 months later.

One of the largest studies of covid-19 long-haulers has proved what many doctors suspected: Not only are many patients suffering a raft of health problems six months after infection, they’re also at significantly greater risk of dying.

Do people recover from long covid?

The health trajectories of covid survivors vary widely – from a complete resolution and a return to previous level of health in most people, to needing lung transplants in a small minority.

A UK study of hospitalised patients published in January found that a year after discharge, fewer than three in 10 patients reported feeling fully recovered.

It’s possible the use of treatments for covid, including monoclonal antibody therapies and antiviral medications, reduces the likelihood of long covid, though this hasn’t been demonstrated.

There is emerging evidence that multidisciplinary rehabilitation services can improve a patient’s prospects of recovery.

Long covid's impact on mental health has given rise to fears of a jump in suicides. (Image: Getty)

Long covid's impact on mental health has given rise to fears of a jump in suicides. (Image: Getty) What are the broader implications?

Long covid's impact on mental health has given rise to fears of a jump in suicides. (Image: Getty)

Long covid's impact on mental health has given rise to fears of a jump in suicides. (Image: Getty) What are the broader implications?

The disability attributable to long covid could account for as much as 30% of the pandemic’s health burden, researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine estimated.

An uptick in treatments for depression, anxiety and pain has stoked concern of a spike in suicides and opioid overdoses.

Surveys of long covid sufferers indicate the condition is leading to reduced work schedules and absenteeism, which has implications for labour productivity. With more than 560m confirmed infections worldwide as of mid-2022, even a small share with long-term disability could have enormous social and economic consequences.

The US Government Accountability Office said in a March 2 report that long covid could affect the broader US economy through decreased labour participation and an increased need for use of Social Security disability insurance or other publicly subsidised insurance.

Do other pathogens cause prolonged illness?

Yes, scientists say it’s actually an expected phenomenon. For example, post-viral syndromes can occur after the common cold, influenza, HIV, infectious mononucleosis, measles, Ebola and hepatitis B.

Diabetes and other long-term consequences were observed in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or Sars, which is caused by a related coronavirus.

A Canadian study identified 21 healthcare workers from Toronto who had post-viral symptoms for as long as three years after catching Sars in 2003 and were unable to return to their usual work. Some people who were hospitalised with Sars in Hong Kong had impaired lung function two years later, a study of 55 patients published in 2010 found.

Still, it’s not known yet whether the lessons of Sars are applicable to covid-19. Long covid shares characteristics with many other long-term health conditions, including chronic fatigue syndrome and a blood-circulation disorder known as POTS. Studies into the drivers of long covid could improve understanding of the causes of these conditions also.

What is being done?

In the US, the National Institutes of Health was allocated $1.15 billion ($2.4b) in funding to support studies into the long-term effects of covid. The researchers hope to get at issues such as the underlying biological causes and how they might be treated and prevented.

Some researchers are pressing governments to focus attention on potential long-term organ damage. For example, researchers have shown the virus can infect insulin-producing pancreatic tissue, potentially triggering diabetes that in some cases persists beyond the acute infection. That’s prompted Australia’s Monash University and King’s College London to create a global registry for studying “new onset” diabetes.

Some long-haulers have reported feeling better after receiving a covid vaccination, prompting researchers to examine the phenomenon and whether vaccines can offer clues to treatment. Avindra Nath, clinical director of the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, said vaccines, including for flu, have been known to help patients with chronic fatigue, but relief has almost always been temporary.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

For more articles like this, please visit bloomberg.com.