A long-out-of-print travel book shows that the past truly is a foreign country. In New Zealand, we did things very differently back in the day.

Robin W Winks spent around a year here on a Fulbright scholarship in the early 1950s to study the Ringatū and Pai Mārire/Hauhau religious movements. He travelled extensively around the country and spent time in Pākehā and Māori households.

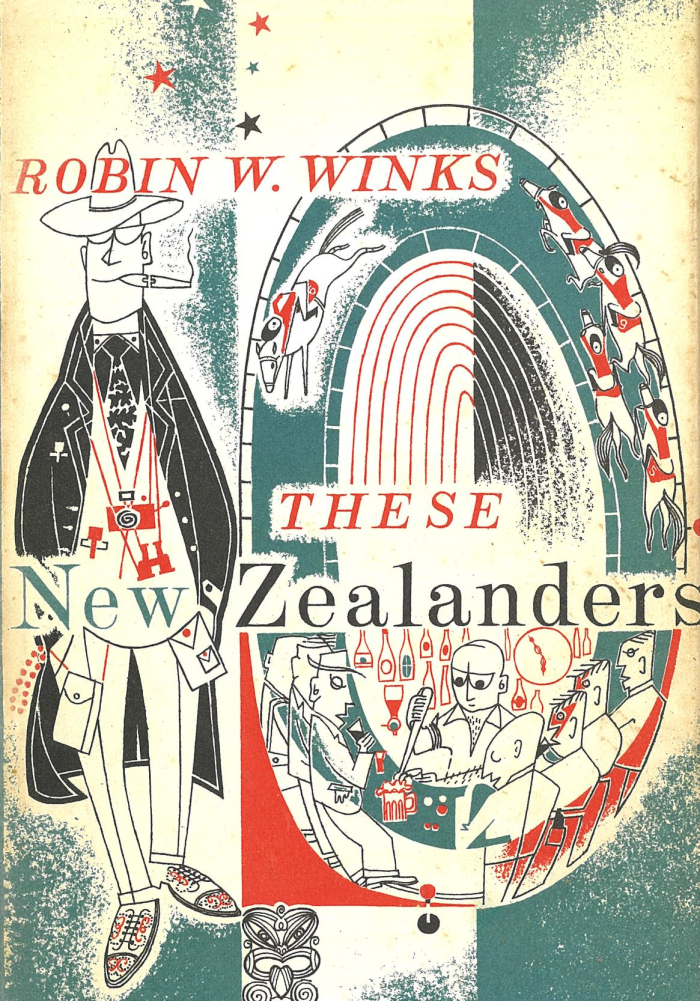

His book These New Zealanders was published by Whitcombe and Tombs in 1954.

The author had been studying history and anthropology at the University of Colorado, and developed an intense interest in Māori culture, beginning with a study of the NZ land wars of the 19th century.

Contemporary readers would have enjoyed this mirror to their little piece of self-proclaimed paradise, although Winks is not entirely complimentary.

To get a picture of NZ, he consulted other Americans living here to create a fairly uniform consensus, probably because many were fellow Fulbright scholars.

The Americans all agreed that the North Island was far more scenic and interesting than the South Island. The forests of the Urewera Ranges, the "rugged grandeur" of the East Cape country and the capital, Wellington, were all described as outstanding sights.

Auckland was too American and generally colourless – "a 1910 San Francisco with a British accent" – while New Plymouth’s “exceptionally ugly” town centre was offset by attractive suburbs.

A nation of drunks

One American the author consulted thought NZ was "a sinful hole", but that was a temperance lecturer. Winks himself was appalled by the 1950s drinking culture. He saw more drunks in a week than he'd seen in a lifetime of travelling.

That this inebriation was achieved mostly with beer confounded his compatriots. "How it is possible to lose control of one's senses on beer is a question all American visitors to New Zealand have raised,” Winks wrote.

He identified the notorious "six o'clock swill" as a major contributor to public drunkenness. Six o'clock pub closing was abolished only after a 1967 referendum.

Coming from an America that had ditched prohibition 34 years earlier, Winks saw such efforts to reduce drinking as futile and self-defeating.

Not that he was a wowser. He considered Wellington's Royal Oak Hotel, demolished in 1979, to be one of the four decent pubs in NZ.

Living standards

Many of the differences between NZ and the US of the time were because America was simply far wealthier and more modern than other Western countries, with its home appliances, supermarkets and car-based culture.

When Winks was in NZ, people kept perishable food in the meat safe and boiled the copper to do the laundry.

They also had wire-sprung mattresses on their beds, something that tormented the author, who was accustomed to America’s inner-sprung mattresses.

After one terrible night on such a hotel bed, Winks was woken at 7am by persistent banging on the door of his room and shouts of “your tea!”. He ignored them.

After five minutes of peace, the bolted door came under a renewed assault of loud blows; Winks finally crawled out of bed and opened it, only to have a cup of tea and biscuit thrust at him. "You must have your tea!" barked the hotel staffer before stalking off.

Such was the state of NZ’s hospitality industry mid-century.

Culture

Horse racing was huge in the 1950s – perhaps because there was not much else to do – and Winks admired the “fine stands and facilities”.

Despite his strong interest in Māori culture, there are only a few references to Māori and their place in this country. Māori music was popular with resident Americans; Winks himself declared that "Māori music is one of New Zealand's finest cultural exports to the world". It was, he considered, the only thing that distinguished NZ culture.

Winks had high praise for the country’s emerging literature, public radio, and art galleries.

But while Britain provided a rich heritage to draw on, a distinctive NZ style had yet to emerge.

Some of the little things fascinate. New Zealanders in the 1950s used to put mustard in their tea, and the author found our coffee perfectly fine. There was great milk and butter, and terrible soapy cheese.

Mutton was so common it came out of our ears. Teeth came out of our heads, too, because of the lack of vitamins in the cooked-to-death vegetables.

Tooth decay was assisted by NZ's excellent chocolate, as good as the British stuff.

Gloves off

Despite his affection for NZ and its people, Winks had a few things to get off his chest. In the concluding chapter, he staked his corner: "Is it possible to love something without respecting it?" he begins.

There follows a paragraph-long love letter to NZ, which even then includes some backhanded compliments. "I admire the people ... for their ability to eat the food they eat and sleep on the [wire-strung] beds they use without complaining or even wishing for anything better."

Then the gloves come off. "I cannot respect the New Zealander for his desire to be 'protected' from cradle to grave, for his sloppy and inefficient work, for his pseudo-intellectuality in his universities, for his slobbering and sickening drinking habits, for his pre-occupation with himself, the races [he means horse-racing], and insular New Zealand.”

He found our provincialism, narrow-mindedness, self-pity and self-praise unappealing.

“I dislike his inability to recognize the facts around him; that he does have a minor race problem [definitely not horse-racing here]; that there is poverty in his nation – the poverty of a lack of spiritual roots."

In the 1950s, NZ was living a quiet, comfortable existence (apart from the wire-strung beds) backed by booming commodity prices. But the national policy of import substitution was ineffective at producing quality goods suitable for export, innovation, or improving productivity. Something would probably have to change sooner or later.

Winks did demonstrate his love for the people here by marrying one of them shortly before leaving. And unlike some American cynics he mentions, he said he wasn't trying to save her from living in NZ.