OPINION: Labour's timely bribe

The 2020 election campaign has now started.

Labour's declaration of a new, larger infrastructure spending package for release just before everyone heads to the beach for the summer is politically masterful.

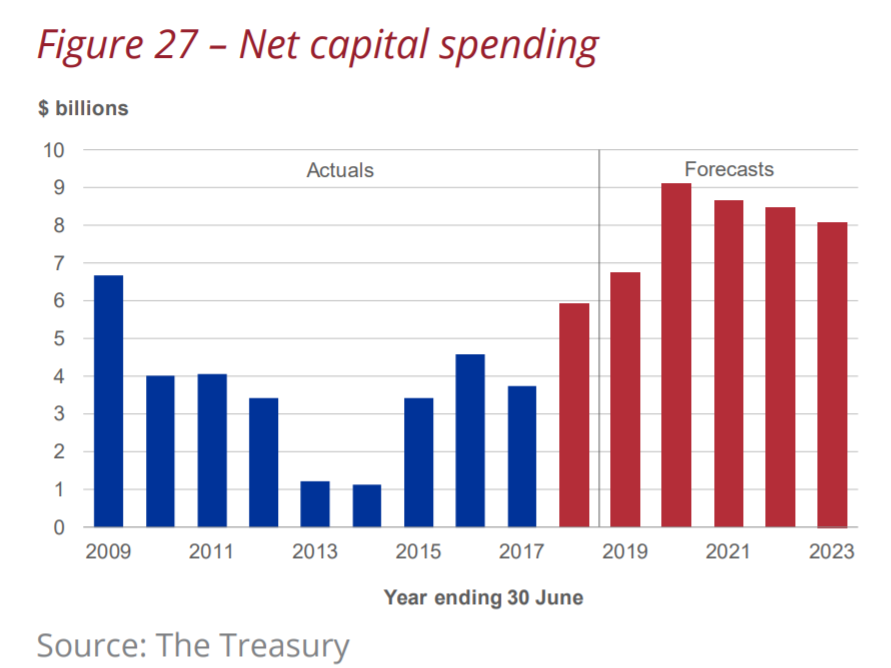

For a start, it comes after two years of Finance Minister Grant Robertson being beaten up from the left, and then all manner of economic commentators across the political spectrum, for hugging so tightly to the debt targets in the Budget Responsibility Rules that both Labour and the rather more reluctant Greens signed up to before the last election.

The role of the BRRs, as they are sometimes known, was less about economic management than political necessity.

Whether fairly or not, Labour administrations have less credibility with financial markets and investors than their more conservative, but more avowedly capitalist, National Party-led governments.

Robertson has not only been willing to weather his critics, but also patient enough to let this alternative chorus of international credit ratings, international economic advisory agencies like the IMF and the OECD, and practical observers of New Zealand's yawning public infrastructure deficits, grow to a crescendo over the course of this year.

The reward is that the rating agencies all have New Zealand on at least a AA credit rating and have indicated they won't bat an eyelid if the government decides to lean against a slowing economy by investing in things the country clearly needs.

Robertson's key sentences in the weekend announcement were these: "We have this once in a generation opportunity because of the government’s good management of the books and resulting low debt. It makes sense to take advantage of this low debt and record low interest rates to make investments now to benefit generations to come."

That is the first time he has come out and said he agrees with a line of argument that has been as cacophonous this year as it has been uncontroversial for a country with among the lowest Crown debt levels in the OECD, rampant population growth, and a generation of fiscal conservatism.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's announcement of between $50,000 and $400,000 in one-off capital maintenance grants for every New Zealand school was a politically well-pitched taster of announcements yet to come.

Expect a drip-feed between now and the Dec. 11 Budget Policy Statement, which will set the tone for the mythical barbecue conversations that Kiwis are said to have over the Christmas-New Year period and set the political tone for the first part of the countdown to polling day, some time between September and November next year.

This is a long way from the 'helicopter money' concept espoused by some commentators, who believe the best way to boost the economy would be to raise all incomes immediately through permanently higher benefit and family support payments. That approach would create a permanent uplift in new spending that would have to be funded every year.

Spending increases of that sort would risk a swift change of heart among the credit rating agencies and financial market commentariat about the government's commitment and ability to keep balancing the books and control debt.

In this version of helicopter money, spending is skewed to investing in small to very large-scale projects: one-off commitments of funds that also, handily, don't show up directly in the annual Budget balance calculation since they count as capital rather than operating spending.

Note, too, that Robertson has not yet said he is actually abandoning the Budget Responsibility Rules. The package will be delivered over the many years it takes for major new infrastructure to be built. In theory, the government could produce eye-popping additional multi-billion dollar sums without necessarily putting much pressure on the debt ratios in the Crown accounts year-to-year.

He knows as well as anyone that while New Zealand's infrastructure needs are urgent, it lacks a sufficiently large skilled workforce or enough companies of sufficient scale and sophistication to deliver a huge amount of new work in short order.

This will be a multi-year vision rather than an immediate building boom, in part because the country's ability to feed a boom remains limited by factors quite unrelated to the strength of the Crown accounts.

Comments