What does the government dream of? A good news story.

How it's been handling the health system has brought it non-stop, escalating negative media attention, much of it driven by the increasing concerns and frustrations of those working at the frontline.

So, a good news story is what the government was hoping for when it released its Interim Health Plan (Te Pae Tata) on Oct 28.

The aim of the plan, a legislative requirement, was to set the health system’s priorities for the next two years.

It was developed by the two new poster-child structures created by the government’s health restructuring – Health New Zealand (Te Whatu Ora) and the Māori Health Authority (Te Aka Whai Ora).

So, was it a good news story?

Horror news day

Imagine the government’s horror when the very next day the front page of the Dominion Post greeted its readers with a headline saying ‘Critics unimpressed by plan’.

Imagine the further horror when it read the strong criticisms from the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists which, along with the other main health unions, had been very reluctant to be seen to be criticising the restructuring that led to district health boards being replaced by Health NZ.

The guts of attacks from within the health system is the lack of wherewithal to deliver on its aspirations.

In other words, there's been an lack of planning to address the workforce shortages that are brutalising health professionals.

Now, it's a mega-crisis

This was a crisis under the former National government and, through neglect, has now evolved to a mega-crisis under the Labour government.

In reality, the plan is a statement of aspirations. Much of it is worthy, but much of it has been said before in different documents.

The emphasis on population health suggests that this is something new. But population health was a central feature when area health boards were set up under both National and Labour governments (1983-93) and further strengthened by former Labour health minister Annette King’s legislation setting up district health boards in 2001.

The new plan is a cobbling together of various initiatives and positive ideas that have been in germination or development for some time, but with an added reference to the pandemic and more repeated references to Te Tiriti principles.

It is then put together in the context of the new national structures and more centralised health system that we now have.

Aside from that, there's little in it that's new or advanced.

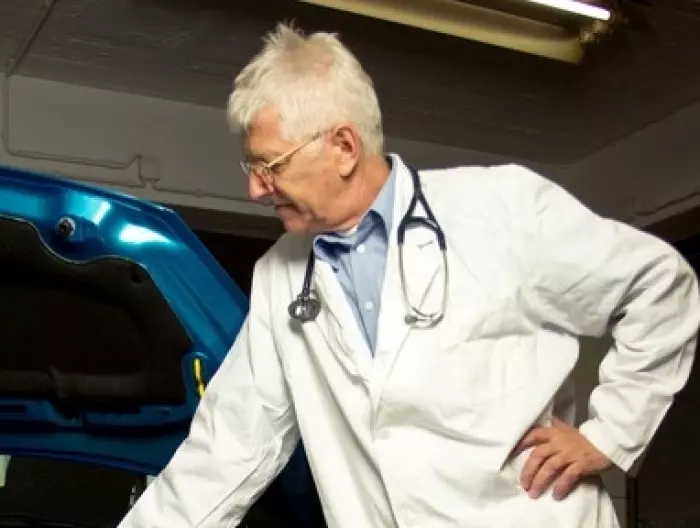

This aspirational statement is like a car without an engine. The engine is the health workforce.

it admits that serious workforce shortages exist, but then simply deals with them through very generalised and intangible ‘to do’ statements.

Further, the critical issue of having terms and conditions of employment that are internationally competitive, particularly with Australia, doesn’t get a mention. And this is at the cornerstone of Te Whatu Ora’s ability to recruit and keep health professionals.

Also absent was the recognition that this workforce is the prime generator of continuous improvement and innovation in the design, configuration and delivery of health services. This is often referred to as 'distributed clinical leadership'.

However, it's not just the lack of the wherewithal to realise the plan's aspirations. It's rationalised by a false narrative.

False narratives are not new. They've defined the government’s rationale for restructuring health.

False narratives

These false narratives started with the misleading claim that NZ had 20 different health systems. In fact, we had a national system where, because of practical necessity, healthcare was delivered locally to geographically defined populations.

At the same time, there was another false narrative claiming district health boards were responsible for a ‘postcode lottery’ where access depended on where you lived.

In fact, healthcare access was determined by external social factors of health, primarily poverty, which were outside of the control of DHBs and the wider health system.

The new false narrative is the claim that this national health plan replaced the annual plans of the 20 DHBs. Nonsense.

There was no national document called a ‘plan’ but there were national strategies. As well as the overarching NZ Health Strategy, there were separate strategies for primary care and healthcare for Māori, Pacifica, disabled persons, women and rural communities.

In a nutshell, the 20 DHBs were the application of these national strategies, along with other legislative requirements, to the geographically defined populations they were responsible for.

These populations varied: large urban, smaller provincial cities and those predominantly rural. There was a lot of variation in socioeconomic status and ethnicity.

Further, if you were to take this false narrative to its logical conclusion, then you would have to also consider the locality plans for the 80 localities Heath NZ is responsible for setting up and determining.

Check my maths

I don’t claim to be a mathematician, but I’m pretty sure that 80 plans is a lot more than 20 ... four times more would be my guess.

It remains to be seen how implementing the health plan will progress.

But no matter how worthy it is, not having the wherewithal (workforce) to deliver it and basing it on a false narrative are serious body blows to its credibility and effectiveness.