In a new series, we’re unpacking New Zealand’s productivity problem, our polite form of capitalism, and the $113b cost of drift, as Dileepa Fonseka explains.

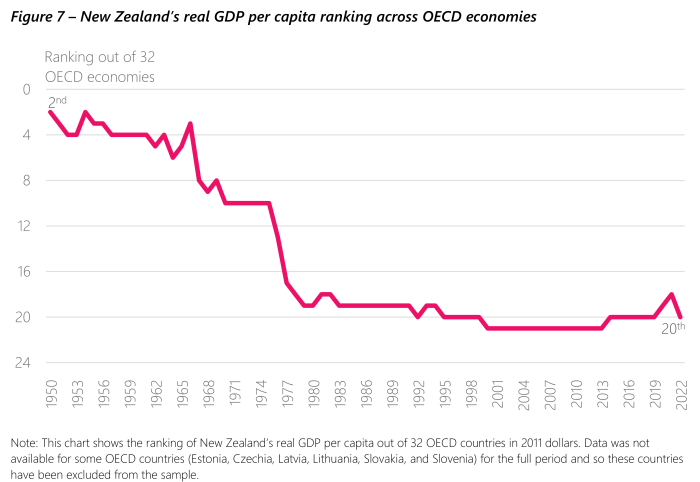

When it comes to productivity, New Zealand was at the front of the pack.

After World War II, the English-speaking economies of NZ, Australia, the United States and Canada were in better shape than war-torn Europe, and so our country had the third-highest GDP per capita in the world.

But the warning signs around future growth were also there.

American economist Mancur Olson once drew up a table showing, out of a group of 18 high-income countries, NZ had the third lowest per capita GDP growth rate during the 1950s, and the lowest growth rate within this group in the 1960s.

Former Productivity Commission head Murray Sherwin said NZ’s actions in the decades after World War II set the country back so far in terms of productivity, it has never fully recovered.

“Things began to go backwards in the 1950s, and I think it’s not coincidental that was when we decided that being an agricultural nation was last century’s business.”

New Zealand's post-war slide. (Image: RBNZ)

Sherwin said NZ started thinking it had to become a manufacturing powerhouse, and so it put in place subsidies and tariffs that gave its citizens some of the world’s most expensive shoes, cars, and clothes - well, expensive relative to the quality of what was produced anyway.

“That’s when the slide was really under way in terms of living standards relative to the rest of the world.”

In the late 1990s, productivity growth showed signs of improvement, but it never improved enough to bring us up to OECD averages for GDP per hour worked.

In the late 1990s, productivity growth showed signs of improvement, but it never improved enough to bring us up to OECD averages for GDP per hour worked.

Which is where the $113 billion figure comes in.

Infometrics principal economist Brad Olsen has calculated $526 billion is how big the NZ economy would have been in 2023 if we had managed to lift GDP per hour worked up to the OECD average.

GDP per hour worked measures how much output the economy produces for each hour worked.

Olsen said GDP per hour worked in NZ grew 3.4% per annum on average between 2000 and 2023, compared to the OECD average of 3.8%.

By 2023, our total GDP was $413b, $113b smaller than if we had met the OECD productivity average by then, he said.

In other words, if NZ had simply managed to lift productivity to the OECD average by 2023, its economy would have been more than a quarter larger.

“We continue to be more than a quarter below OECD average in terms of productivity levels,” Olsen said.

“We’ve made basically no real progress either, in terms of trying to catch up.”

Introducing ‘Productivity Unleashed’

Over the next few months, BusinessDesk and a small group of reporters are going to be looking at productivity, why it matters for NZ, and what we can do to improve it.

However, first, we should remember NZ isn’t the only country fretting about this issue.

The Australian Prime Minister is convening a productivity summit next month, the OECD has been churning out papers exploring why average annual productivity growth in the 2010s was half what it was in the decade prior, and the UK’s politicians continually debate why their productivity growth numbers lag near the bottom of the G7 wealthiest nations' table.

Brad Olsen says New Zealand continues to be below the OECD average when it comes to productivity. (Image: NZME)

All of this fretting over productivity has also produced interesting answers.

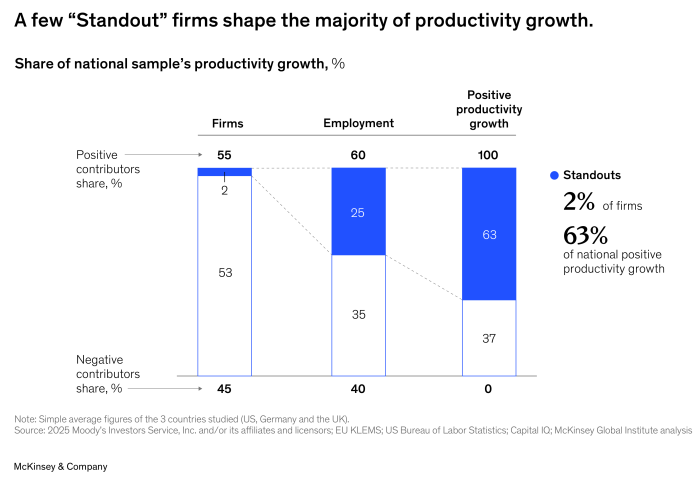

A McKinsey Global Institute study of 8300 large firms across the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom has made interesting observations about what productivity is about.

One of the report’s contentions is that productivity is not really a story of slow and steady improvement, but rather big and bold changes.

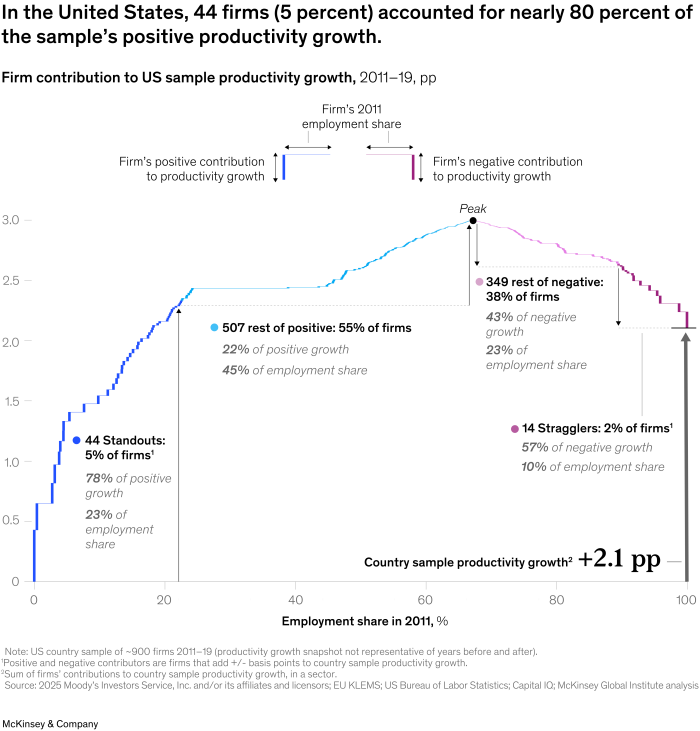

For example, in the US, 5% of firms generated 80% of productivity growth within the sample. Within the study, these firms are referred to as “standouts”.

“In general, standouts are neither the most productive firms nor the firms that are growing productivity the fastest,” McKinsey’s consultants wrote.

Instead, these firms were large enough that the productivity gains they made mattered at an economy-wide level.

Meanwhile, efficiency changes like restructuring and downsizing improved company productivity, but tended not to deliver game-changing productivity results.

McKinsey's work shows how "standout" firms make an outsized contribution to productivity. (Image: McKinsey)

The study also observes productivity is as much about failures as successes.

According to McKinsey’s study, productivity laggards who went out of business made a major contribution to productivity growth simply by going out of business.

Half of productivity generated across the US companies surveyed was generated by low-productivity firms folding up and dropping out of the survey.

Meanwhile, productivity laggards who managed to hang on dragged down average productivity statistics in the UK and Germany: which gets to the heart of why we’re covering the issue of productivity for BusinessDesk.

Even though politicians spend a lot of time talking about productivity as a political issue, most of the questions around productivity are not really about Government; they’re about business, something Sherwin stresses too.

“Productivity is fundamentally a private sector issue, but the context matters a hell of a lot, and what governments do is set the context.”

A small number of "standouts" boosted US productivity, but there were "stragglers" who also brought it down. (Image: McKinsey)

This context can include infrastructure and education, since increasing productivity is often about investing in human capital.

From Sherwin’s perspective, and others too, the dynamism of NZ’s corporate sector also leaves a lot to be desired when it comes to productivity.

“We have firms that hang on forever, with modest returns on equity.”

Then there are the smaller companies, those often characterised by owners who aren’t seeking a big return and are happy to hang on as long as their company supports their lifestyle.

Over the years, Sherwin has also found himself looking at lists of NZ’s largest companies, not just the listed ones, but the largest ones overall.

Murray Sherwin says productivity is a private sector issue, but Government matters too. (Image: NZME)

A lot of them are farmer-owned co-ops, state-owned enterprises or foreign-owned companies servicing the domestic market, he observed.

“There aren't very many of them that are committed to being able to perform and sell into international markets.”

Sherwin said the NZ market was small and until firms got into foreign markets, they often didn’t face the kind of competitive pressures driving the most productive firms overseas.

It’s not all bad

There are good news productivity stories in NZ among all of this as well.

Even though we might not have made the progress we would have liked, we have still made progress.

In the 1910s, a single cow would deliver between 2,000 and 3,000 litres of milk every year, and by the 2010s, this had risen to around 4200 litres on average.

No doubt, a portion of this productivity was enabled by the invention of rotary milking platforms by Taranaki farmer Merv Hicks in the 1960s; which shows how productivity growth can be characterised by abrupt leaps.

Reserve Bank of New Zealand chief economist Paul Conway also believes productivity is not just about what Governments, or even companies, can do.

“When you ask the question: how do we lift our productivity, there’s clearly things the Government could be doing, there’s things that businesses could be doing, and there’s also things that people – consumers and workers – could be doing.”

Paul Conway says there are contributions players at all levels of society can make to productivity. (Image: NZME)

One of the things consumers could be doing is voting with their feet: shopping for the best deal to drive competitive pressures in the economy, Conway said.

“It’s very hard to compare measures of competition and creative destruction across countries, but to the extent that it’s been done in the past, it does suggest that our markets are weak on the competitive front.”

Conway has a long history of research around productivity issues and served as a director of research at the now-disestablished Productivity Commission for eight years.

His interest in the issue stretches back even further than this; if you look through the Reserve Bank’s archives, you’ll even find a paper jointly authored by Conway and a certain Adrian Orr on NZ’s productivity history.

Conway said the focus on frontier firms was fine, but what was sometimes left out of the conversation were the firms a little further back from the frontier.

“What’s happening to the rump of New Zealand businesses that are doing the same thing year after year, decade after decade, and even generation after generation?”

Conway said diffusion of technology within NZ to these types of firms was something the country had struggled with because adopting new technology wasn’t simply about buying new equipment, but also having the skills to integrate technology within their business.

“If you gave me the option, ' would you rather have 10 firms in New Zealand pushing out that frontier’, or ‘would you rather have hundreds of thousands of firms catching up to our domestic frontier?’ I would choose the latter.”

So our series will also include a look at private sector performance, taking a look under the hood at why NZ’s corporate engine isn’t powering productivity the way it should.

Is geography destiny?

Then there are the geographic handicaps NZ faces when it comes to productivity.

Unlike other small, advanced economies, we are not only small but also physically distant from major markets.

Copenhagen is 700 kilometres away from Frankfurt, Dublin is 460km from London, but Auckland is more than 9000km from Hong Kong.

Over the past few decades, population growth, migration to the cities, technology and the increasing importance of knowledge to economic growth, have also led to the growing importance of cities to the productivity question, something Conway acknowledged as well.

“Cities are one of humankind’s most productivity-enhancing innovations of all time: coming together, living on top of each other, exchanging ideas at work; this is how innovation and diffusion of new technologies work,

“So it’s clear that bigger, denser cities and countries tend to be more innovative.”

NZ's population spread poses issues for productivity, but it has other advantages. (Image: NZME)

And so, it will be important for the Productivity Unleashed series to also take a look at cities and NZ’s population growth, but also whether NZ’s geography and population spread means significant productivity growth is just too difficult to achieve.

KPMG's head of consumer/industrial markets and agribusiness, Ian Proudfoot, pointed out this year that NZ always compares itself to small advanced economies, but those advanced economies have much higher population densities than we do.

He argued that for a country of our size, a population of 20 million was more realistic to drive living standards, and believed the country needs better population planning to accommodate this kind of growth.

“I don’t claim to have all the answers, but by my thinking - and the scenarios I keep running and thinking through and testing with people - suggests that five million people in a country the size of NZ isn’t going to deliver us the infrastructure we need to achieve the economic growth we desire, and we have to think differently about what the population base of the country needs to be if we want to achieve that economic growth.”

He argues that when a country has a higher population density, it is easier and more efficient to provide the infrastructure for it.

Infrastructure is also said to be a great driver of productivity and growth, so Productivity Unleashed will look at infrastructure too.

However, the idea that NZ needs to be bigger, or smaller, to drive economic growth and productivity is a controversial one.

For example, while Conway accepts the benefits of cities, he is not personally one of those who thinks population growth is the answer.

“I’m not part of the group that thinks New Zealand should be 25 million people … I mean, I’m open to that conversation, but I think there’s ways we can lift our productivity while still retaining who we are as a country - and part of that is lots of wide open space.

“I don’t think economic geography is necessarily destiny in terms of our productivity performance.”

The next frontier

Businesses right now are also in the midst of a major productivity-related debate around artificial intelligence, and how to use the technology.

This technology could be a real step change for NZ businesses who, as Conway and others have observed, tend to throw “hours worked” at a problem, rather than capital or technology.

The impact of technology on productivity throughout history can often seem hyperbolic when cited by futurists and tech boosters, but in a sense, it can’t be overstated.

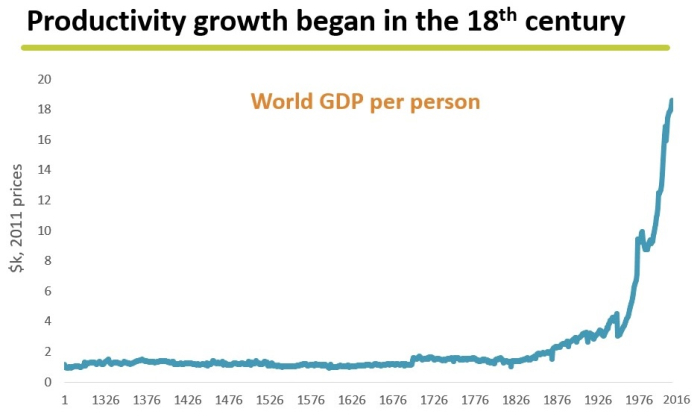

When he talks about productivity, Sherwin sometimes throws up a graph showing productivity through centuries of human history.

It shows economic growth largely hovered around less than quarter of a percent per year for centuries of human life, meaning the economy and society didn’t tend to change much within a person’s lifetime over these periods.

This situation changed during the Industrial Revolution, with technology improvements and the returns from knowledge compounding over time.

Slow annual productivity growth was the norm for hundreds of years of human history. (Image: Murray Sherwin)

Now, we are used to technology changing the world every year, and the latest developments in AI are pushing those expectations even further.

It has only been 32 months since OpenAI made a blog post introducing the world to a new product it had made called “ChatGPT”.

“We’ve trained a model called ChatGPT which interacts in a conversational way,” OpenAI wrote on November 30, 2022.

“We are excited to introduce ChatGPT to get users’ feedback and learn about its strengths and weaknesses."

If today is what the world looks like 32 months on from the introduction of ChatGPT, it’s worth asking what the world might look 32 months from now.

And so, the first two stories in our Productivity series start at a conference around AI products in Sydney, part of a global scramble by private companies who are desperate not to be left behind by AI, which is the first technology that can improve itself, by itself.

Even now, another shift in AI is occurring, as the technology moves away from the conversational chatbots we’ve used over the last 30 months, to agentic AI where the technology doesn’t just talk and advise, but does.

In a story set to be published this week, ServiceNow country manager Kate Tulp tells BusinessDesk’s Cecile Meier NZ businesses are embracing AI cautiously, fearful of its consequences, but she also points out that not adopting a technology carries a cost too.

“If we’re too judgy or hesitant, we will miss this wave and our children’s children will judge us for it.”

Because, as Sherwin observes, if there is one key weakness NZ Inc has displayed when it comes to productivity, it is around the boldness within our companies.

“It’s big, bold strategic stuff that makes the difference … our problem is that it’s really hard to grow big, dynamic firms out of New Zealand,” Sherwin said.

This is editorial produced by our journalists. Spark is a sponsor of the Productivity Unleashed series but does not necessarily endorse these articles/it is not its opinion.

Read more in the series as it progresses here.