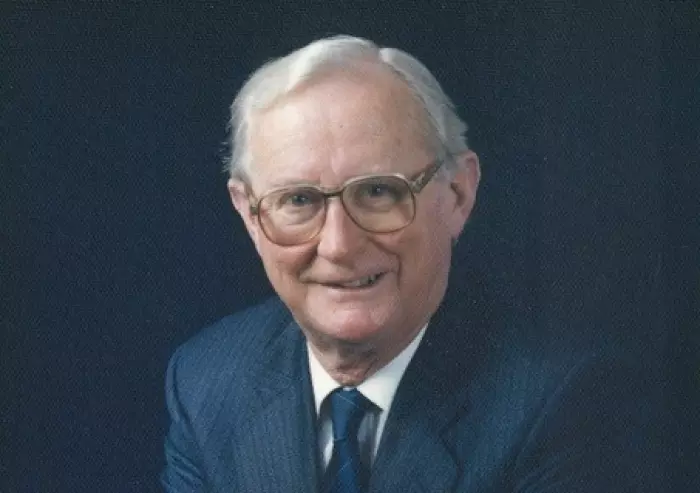

Alan Burnet, who died at the Jane Winstone Retirement Village in Whanganui on 18 July aged 101, was an accountant from the provinces who rose to become the dominant figure in the New Zealand newspaper business.

Burnet was head-hunted by a young Rupert Murdoch in 1964 to run Wellington’s struggling morning daily The Dominion, in which Murdoch had recently acquired a substantial stake.

He ended up reshaping the entire industry through a series of bold mergers and takeovers that ultimately resulted in what is now Stuff – although Stuff is a pale shadow of the company Burnet left behind when he retired in 1993.

Born in Whanganui and educated at Whanganui Collegiate, James Alan Burnet got his first job in 1937 as an office junior for the Wanganui Hospital Board.

He trained as a navigator in the Second World War and served with an RAF squadron of Mosquito night fighters, but saw little action.

Hands-on job

Returning to NZ, he began training as an accountant and joined the staff of the Wanganui Chronicle, where his father-in-law was managing director. It was a hands-on job in which Burnet would sometimes drive the Chronicle delivery car, starting at 1am on a run that took him as far north as Waiouru, Ohakune and Raetahi before returning to put in a full day at the office.

He eventually succeeded his father-in-law as manager of the Chronicle and settled into what might have been an uneventful career as the boss of a moderately successful provincial daily.

That all changed one day in 1964 when an emissary arrived with a proposition from Murdoch.

The ambitious Australian newspaper heir had outmanoeuvred high-powered rivals to get a controlling interest in the Wellington Publishing Company, which was the owner of the Dominion. The purchase was Murdoch’s first acquisition outside Australia and the first step on his march to global pre-eminence in the media.

Murdoch needed someone to invigorate the sleepy Wellington daily, which had been started in 1907 by moneyed families from Wellington, the Wairarapa and Hawke’s Bay.

It was still run so conservatively that directors would meet once a week to sign cheques rather than delegate the responsibility to company executives.

The Australian had heard about Burnet from NZ contacts and thought he might be the man for the job.

It proved a smart choice. Burnet promptly asserted himself by insisting the paper publish accurate circulation figures, rather than the grossly inflated ones that disguised its lacklustre performance.

Corporate marriage

He soon saw that the Dominion was vulnerable on its own and set about building a more diverse base that would help protect the company against downturns.

In 1965, Burnet was involved with Murdoch in launching sister paper, the Dominion Sunday Times (a forerunner of today’s Sunday Star-Times), and in 1970, he engineered a merger with the big-selling weekly Truth. That was a dramatic event in the industry because it was the biggest newspaper merger in NZ history at that time and stirred fears of a media monopoly.

That was followed in 1971 with another corporate marriage, this time with the highly profitable Waikato Times. But those deals were nothing compared with what was to come.

In 1972, Wellington was stunned by the announcement of what had seemed unthinkable – a merger between traditional competitors the Dominion and Wellington’s Evening Post, owned by long-established family company Blundell Brothers.

The deal was quietly and amicably negotiated in a series of discreet meetings between Burnet and Neil Blundell, his opposite number at the Evening Post.

Both men attended an industry conference in Europe and quickly grasped the need for newspaper publishers to adapt to rapidly changing – and very expensive – technology.

The Dominion and the Post had been implacable rivals, with the Post better positioned because of its dominance in the greater Wellington area, its substantially higher sales figures and its highly profitable pages of classified advertising.

If you were looking for a job, a car, a flat or a second-hand bargain, you bought the Post. But television was eating into evening newspaper sales and Blundell sensed – correctly, as it turned out – that the era of family-owned papers was drawing to a close.

Both men could see the benefits of pooling resources. A critical consideration was the huge capital tied up in printing presses that lay idle most of the day but could be put to more efficient use by printing two papers instead of one.

Mergers and acquisitions

The Wellington Publishing Company-Blundell Brothers merger led to the formation of Independent Newspapers Ltd (INL), where Burnet was managing director until 1983 and chair for a further 10 years.

That move was the first of a series of mergers and acquisitions driven by Burnet, although always with Murdoch’s backing.

The Manawatu Evening Standard was the next to join the INL stable, in 1980.

Then came the Southland Times (1984), the Timaru Herald (1985) and in 1987, the biggest prize of all: the Christchurch Press, a paper previously considered an impregnable fortress and a citadel of the Canterbury establishment.

By then Burnet had passed the day-to-day reins at INL to former Evening Post editor Mike Robson, but continued to wield influence as chairman.

There remained only a handful of family-owned provincial titles to be mopped up – the Taranaki Daily News (1989), the Nelson Evening Mail (1993) and the Marlborough Express (1998).

INL also published a nationwide string of profitable community papers and at one point even owned suburban papers in Texas and California – acquisitions that came about through Robson’s American connections. He was married to an American and had been to university there.

Murdoch remained in control throughout and had his own representatives on the board, but as he pursued bigger ambitions in Britain, the US and Australia, he was content to leave the running of INL to Burnet and Robson.

Laments about loss of local control

Meanwhile, INL’s main rival, NZ Herald publishers Wilson and Horton, was scrambling to catch up, eventually buying its own stable of daily papers in Hawke’s Bay, Whanganui (where it bought Burnet’s former employer, the Chronicle), Rotorua, Whangarei and Tauranga.

By the 1990s the newspaper industry had been radically transformed, much of it due to Burnet’s vision and commercial savvy.

The takeover of local papers by INL was invariably accompanied by laments about loss of local control, but the benefits greatly outweighed the disadvantages. It meant access to capital and technology, streamlined management structures, professional career opportunities for staff and even editorial independence, once papers were freed from parochial interests.

And, contrary to a widely held suspicion, editorial policies were not dictated by the INL head office in Wellington. Editors were free to decide their own line.

Not all Burnet’s initiatives were successful.

In retirement, he would lament going along with Murdoch’s urgings in 1968 to change the Dominion from a broadsheet to a smaller, tabloid format.

Murdoch assumed that because tabloids were popular in Australia, they would be well received here, too, but neither readers nor advertisers approved and the experiment was abandoned after four years. It took decades before the tabloid format returned under Stuff.

The Burnet era was marked by other upheavals besides corporate expansion. He was in charge when evolutionary new technology was introduced, and got involved in several bruising industrial disputes as unions fought to protect their members in a period of rapid and unsettling change.

He also clashed privately with prime minister Robert Muldoon in a test of INL’s commitment to journalistic independence.

Infuriated by the Dominion’s vigorous political reporting, Muldoon leaned on Burnet to sack the paper’s then editor, Geoff Baylis.

Politely but firmly rebuffed, Muldoon responded by petulantly vetoing a recommendation for Burnet to be knighted for services to the newspaper industry. He was, however, awarded a CBE in 1991.

A steely core

Although gentlemanly and affable, Burnet had a steely core.

Anyone who got offside with him came out second best. Former Waikato Times chief executive Philip Harkness, who was briefly deputy managing director of INL under Burnet in the 1970s, learned that to his cost when the two had a falling out.

Harkness was a bit too ambitious, as Burnet put it years later, and inclined to overstep his authority. It was clear INL wasn’t big enough for both of them.

In retirement, Burnet returned to his home town, Whanganui, where he and his wife Lorraine had a house overlooking Virginia Lake. In recent years they lived in a retirement village. Lorraine died in 2021.

He had a love of the outdoors that been instilled in him as a boy and he was a keen fisherman, skilled at both surfcasting and fly fishing for trout.

He also enjoyed whitebaiting at Kai Iwi, where he and Lorraine had a beach house, and duck shooting.

His other great interest was horse racing. He successfully bred horses in partnership with Nelson and Sue Schick of Cambridge’s Windsor Park Stud, producing several Group 1 winners.

His son Rob, who followed his father into the media and developed a Sydney-based website specialising in racing news, recalled Burnet Sr as “a leader in life, calm and kind and approachable by everyone”.

Burnet’s daughter Liz Parker also became a journalist of note, starting at The Dominion and later editing women’s magazines in NZ, Australia and South Africa.

Stuff

And what of INL, in its glory days the biggest print media company in NZ history?

After Murdoch withdrew from NZ in 2003, INL’s publishing interests were sold to the Australian company Fairfax, later becoming Stuff – a name originally created for the INL website.

By then, the digital revolution was starting to cause massive disruption in the industry, chewing a gaping hole in newspaper sales and advertising revenue.

Papers radically downsized as they struggled to set up a new business model for an online world – a goal still not wholly accomplished.

The industry’s decline was never more dramatically shown than when Stuff’s Australian owners sold the company to its current proprietor, Sinead Boucher, in 2020 for the token sum of one dollar.

What Burnet thought of the fate of the once-formidable and profitable company he had painstakingly built up over three decades was not recorded.

* This article has been updated to correct the age of Alan Burnet that was incorrectly attributed to him during the subediting process.