Widespread job losses are seen as one of the few shocks that could drive down house prices in certain regions, but property analysts expect national prices will flatline rather than fall.

Those impacts are likely to be most felt in areas such as the Bay of Plenty's Kawerau district, which is facing the impending closure of the Kawerau Norske Skog newsprint mill with the loss of 160 jobs.

That has already been reflected in a month-on-month drop of 17% in the district's median price to $285,000 in April, from $345,000 in March, on a halving in house sales from 12 to six, according to numbers by the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (REINZ).

In the Southland district, where the potential closure of the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter in a few years is weighing on 2,500 employees and contractors, prices also stepped back during April.

In Southland, prices dipped from a median of $415,000 on a 40% decline in sale numbers to 131, from 219 in March. While there is some seasonality to that, it comes after a 31% year-on-year jump in prices for the region, from a median of $307,000 to $402,000 in April 2021.

Nick Goodall, head of research at property analytics firm Corelogic, said while there are fears of a widespread market correction on the back of government moves to slow investor buying and potential change in interest rates, it is likely to take an external event, like unemployment, to push prices lower.

This is because banks' loan-to-value ratios have been in place for some time, meaning the majority of homeowners have at least some equity in their homes.

That means the market will have to "effectively be underwater" before most will consider selling without some external pressure, he said.

That is likely to see some regional disparities emerge, rather than blanket price movements across the board.

Unsustainable levels

Where there is consensus, however, is that house price inflation is now at unsustainable levels.

For the 12 months through April, house price inflation, on a three-month moving average basis – which removes some of the seasonality from the numbers – continued to run hot at 23.9%.

The REINZ house price index for the same period was up 26.8%.

These price rises have brought warnings from banking economists and property analysts that the market is getting unwieldy at current prices.

The Reserve Bank's latest financial stability report suggests the housing market is at a "significant risk" of correction, on the back of government tax policy changes, as population growth slows and as building continues to ramp up.

While a correction typically refers to a 10% decline from a peak in financial markets, analysts find it harder to pin down a strict definition for residential property, and the general interpretation for the local housing market is for prices to stall from next year.

Forecasts are variable as to what that will look like, but Treasury is forecasting a flattening of house price inflation to less than 1% next year, and the consensus among economists predicts the next 12 months will see activity well down on 2020's frenzied buying.

Last week, Stephen Toplis, head of research at BNZ, wrote that the RBNZ has every right to be worried about the prospect for a house price correction, because the longer inflation remains elevated the greater the chance of a "major correction".

That's as record low interest rates have pushed NZ house prices higher than counterparts in other countries, outpacing every country in the world last year, except Turkey.

But with supply now going "bonkers", Toplis suggests NZ is entering a multi-year period when marginal supply will exceed marginal demand, which in turn will put pressure on house prices.

He stops short of predicting a reversal in house prices, but does note that if a price dip were on the cards, it's important to put into perspective that "even if prices fell 20%, it would only take them back to where they were a year ago. For new buyers this would be problematic but for prospective new entrants it would be a boon."

Westpac's acting chief economist Michael Gordon is inclined to agree, suggesting this week that home building levels are now "well above" what's needed to keep up with population growth.

Gordon suggests that the weaker outlook for house prices could also have a dampening impact on residential construction, although this is likely to be more modest as new builds remain exempt from the extension to the brightline test.

Affordability

Corelogic's Goodall said while house prices even at current levels have some people stretching to service their mortgages, the current interest rate environment means most are in a position to continue making bank payments.

So even when interest rates track up, homeowners won't be putting 'for sale' signs up on their front yards, as banks will be keen to work with clients and adjust payments.

Any interest rate hit will also be mitigated by people moving to longer-term rates in the belief rates have hit the bottom of their cycle, he said.

That is supported by recent mortgage numbers from the Reserve Bank, which show that while 78.8% of mortgages in February were on a fixed one-year or floating rate, that had dipped to 77.2% by April.

Property economist Tony Alexander also suggests the mere expectation of an interest rate rise could spark accelerated buying, letting them "lock in" a relatively low rate before rates head north.

Alexander said the concern about inflation could have the same result, with property considered an ideal hedge to rising inflation levels.

First home buyers most at risk?

Last year about 39% of first home buyers had a mortgage with a deposit of less than 20%, making up the majority of buyers in that category.

So to have any kind of impact, Corelogic's Goodall said any real price decline will have to be of the order of 10%, to put those first home buyers into negative territory.

Even so, he said, negative equity isn't really a problem in itself as long as people retain their jobs, something more pressing where large employers are shutting up shop.

At the same time, banks also use stress tests to ensure the amount they are lending – even at high LVR rates – leaves some headroom in the event of interest rate changes.

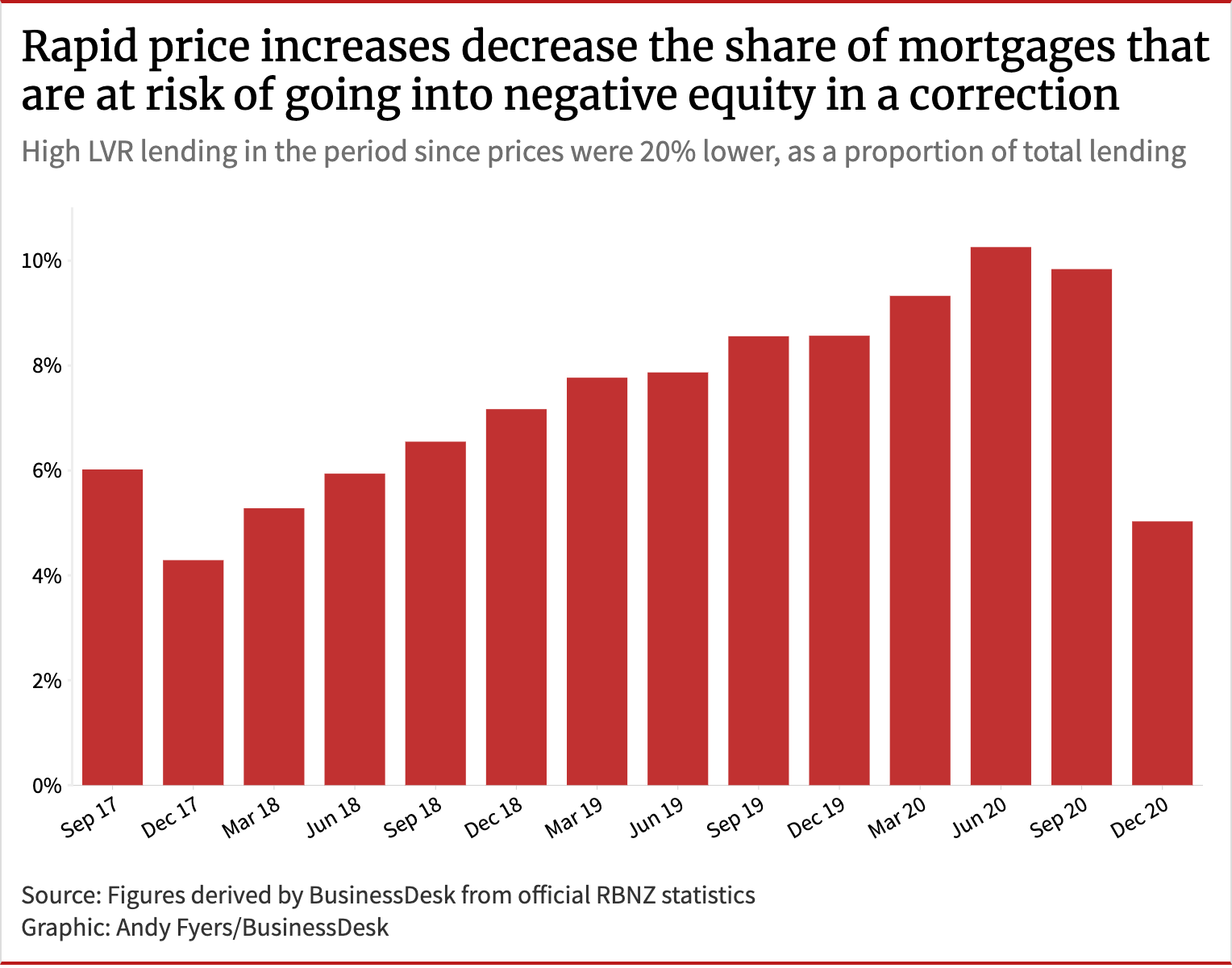

Another side effect of rapidly increasing prices is that it insulates existing owners against a correction putting them into negative equity.

So if prices rise by 20% in a year – as they have done – anyone who bought before that should have at least 20% equity.

The chart shows how as prices increased in 2020 the share of mortgage lending held by owners with less than 20% equity fell.

With many recent high LVR borrowers quickly seeing their equity lifted above the 20% mark. While they might still technically be considered high LVR borrowers, in reality value increases quickly gave them a buffer against a correction.