When WorkSafe was first set up, Pike River widow Anna Osborne, who lost her husband Milton in the disaster, remembers feeling hopeful. But with workplace deaths and injuries still high, that hope has curdled to cynicism.

“WorkSafe was created to be harder and firmer on these businesses and to encourage them to make sure their workplace is safe and nobody gets killed,” Osborne says.

“One death is way too many, but to see the amount we’re still having - the amount of people who are still not coming home after their day at work because of an accident that could have been prevented - is absolutely disgusting. It’s really disturbing.”

The health and safety regulator was set up in 2013 following the West Coast mining disaster that killed 29 men, replacing the Department of Labour's safety inspectorate. Following the tragedy, the government also passed the Health and Safety at Work Act, which came into force in 2016.

Osborne sees few improvements in the five years since.

“To me nothing seems to have changed," she says.

“The only thing that’s changed is the name of WorkSafe. They pat themselves on the back if they’re down a couple [of deaths], which to me is way too many anyhow.”

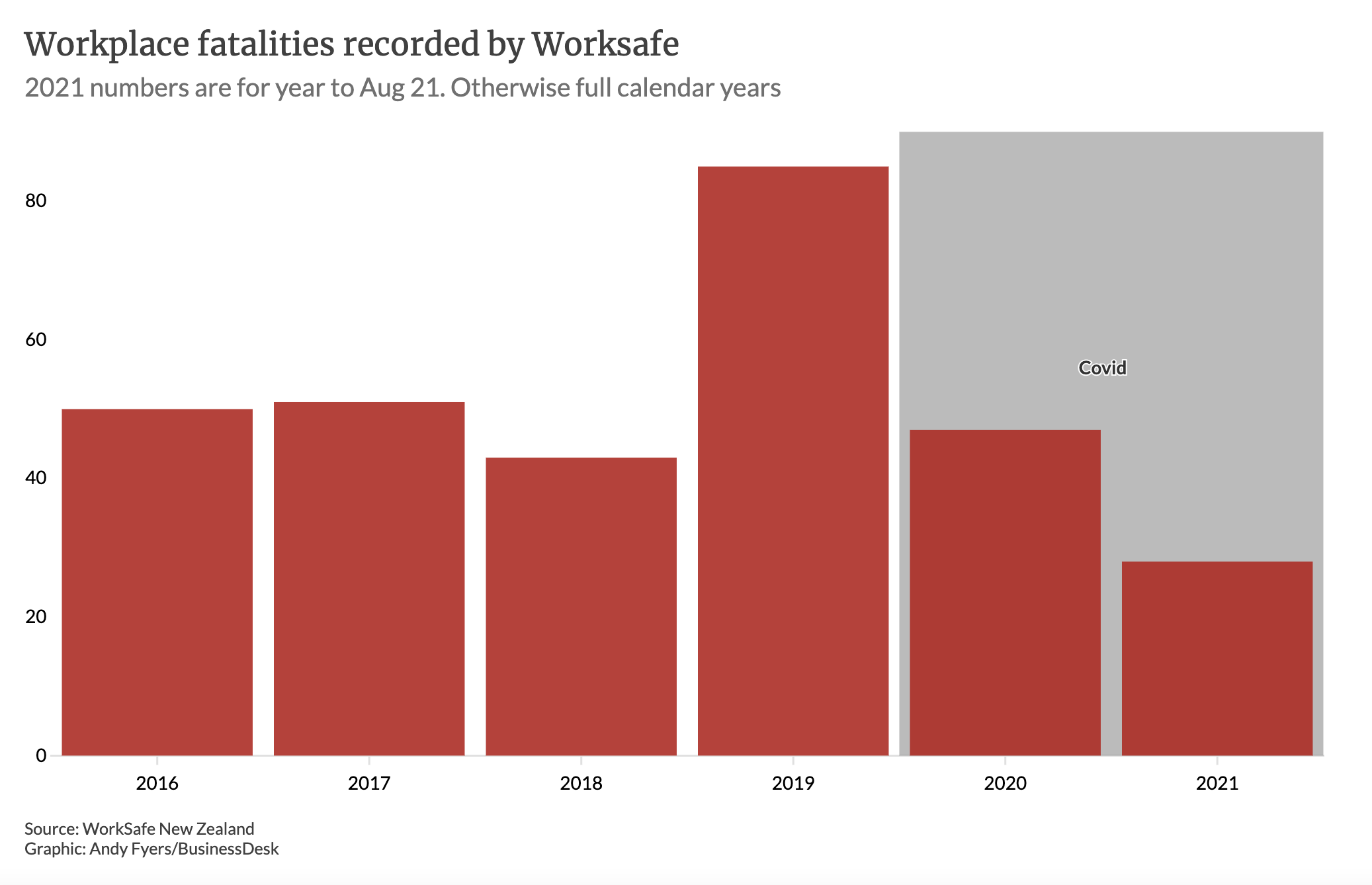

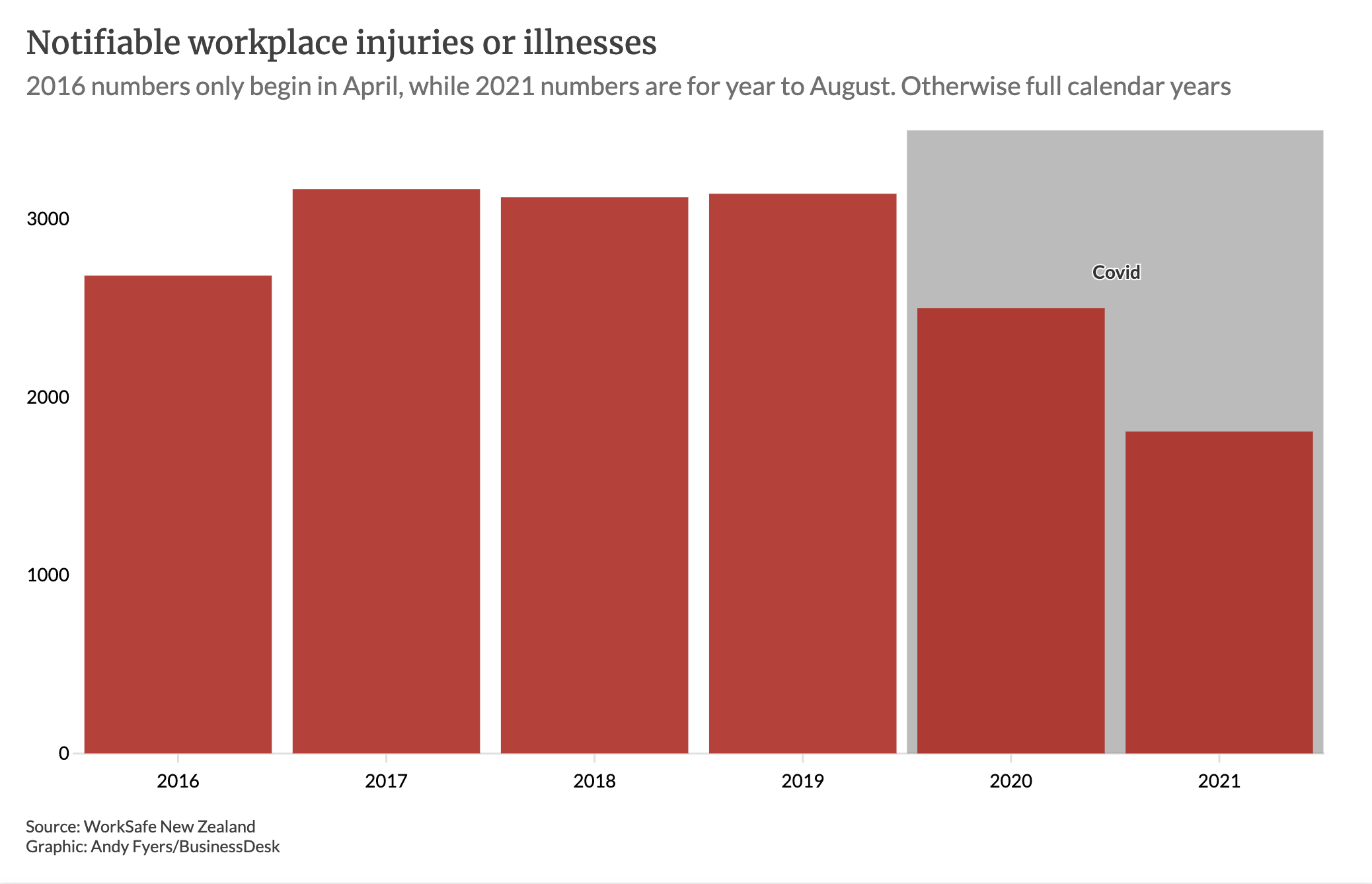

Between 2016 and late 2021, at least 304 people died in workplace accidents, according to figures provided by WorkSafe under the Official Information Act (OIA). The number hovers at about 50 each year, spiking to 85 in 2019 largely due to Whaakari/White Island. Injuries and illness reported to the regulator also remain stubbornly high.

Day in court

For families who lose a loved one at work, Osborne says it’s crucial they get their day in court to “eyeball” the people responsible and seek compensation. The labour department deprived the Pike River families of that when it agreed to drop charges against mine boss Peter Whittall in exchange for a $3.4 million payout, or “blood money” as Osborne described it at the time.

Since 2016, the new OIA figures provided to BusinessDesk show, WorkSafe has withdrawn 128 charges.

In that time, the regulator has taken 413 prosecutions for health and safety breaches resulting in convictions for 354 defendants. WorkSafe went to court the most times - 84 - in 2016, the year the new health and safety laws took effect.

Osborne believes it’s not enough.

Anna Osborne lost her husband, Milton, in the Pike River mine disaster. (Image: Supplied)“They have to prosecute these employers so they set examples for any other businesses in the same industry to actually open their eyes and go ‘oh shit, this is going to hurt us in the pocket’.”

Anna Osborne lost her husband, Milton, in the Pike River mine disaster. (Image: Supplied)“They have to prosecute these employers so they set examples for any other businesses in the same industry to actually open their eyes and go ‘oh shit, this is going to hurt us in the pocket’.”WorkSafe has a range of enforcement measures aside from court action, including infringement notices, which come with instant fines, and prohibition notices, which prevent work taking place until health and safety issues are remedied.

But is it getting the balance right between enforcement and education?

The question gets rehashed all the time. Families bereaved by workplace accidents and denied their day in court have lashed WorkSafe for perceived investigative failings, while advocates and unions have called on the government to better empower the regulator with more resources.

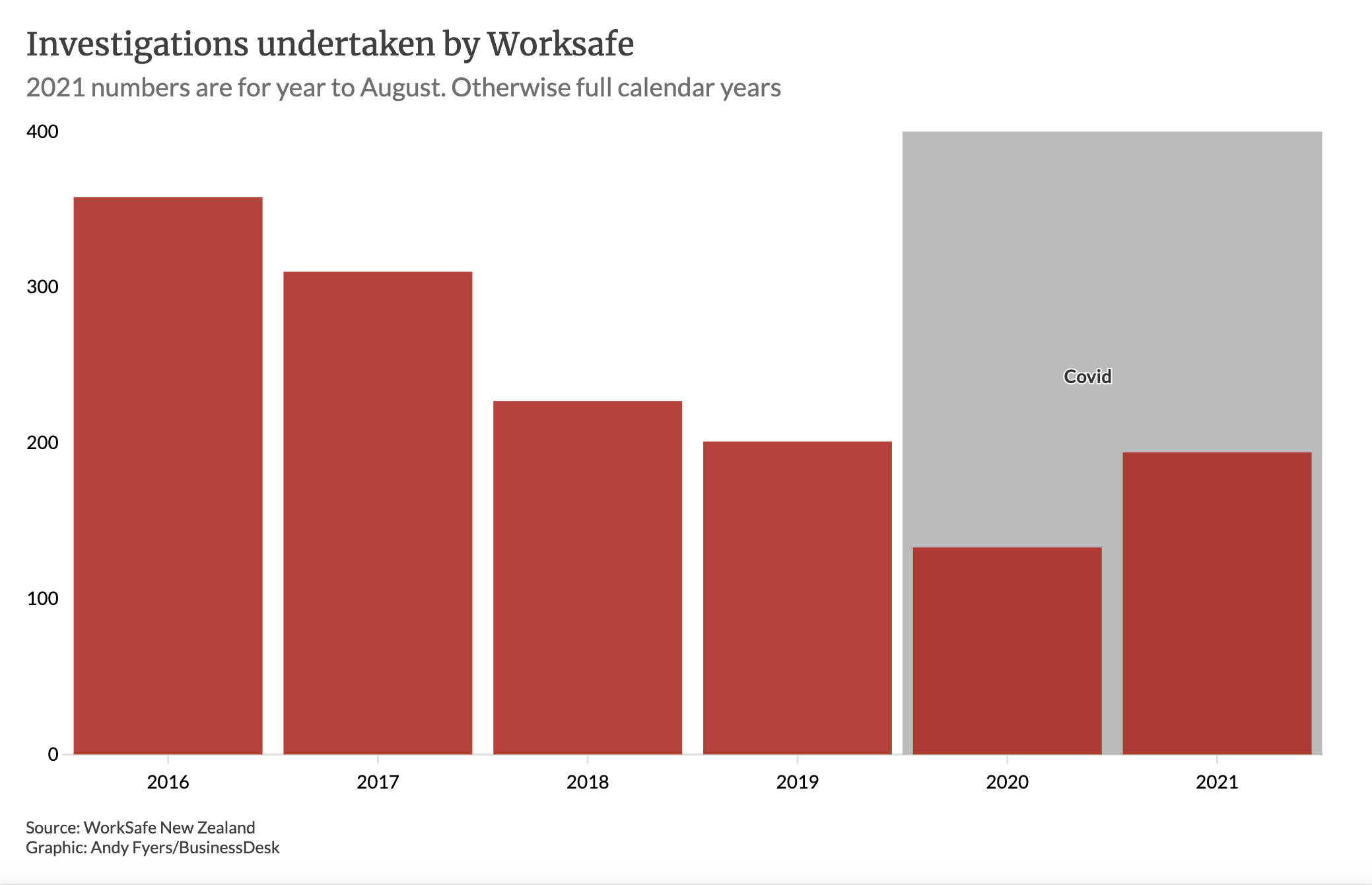

Meanwhile, the number of investigations carried out by WorkSafe - needed to gather evidence for a prosecution - is declining. The OIA shows investigations under the new legislation peaked in 2016 at 358 before dropping to a low of 133 in 2020, rising to 194 in 2021 (the figure captures most but not all of the year).

WorkSafe responds

WorkSafe regulatory effectiveness and legal manager Mike Hargreaves says it’s not possible to investigate all 10,000 to 15,000 complaints received by the regulator each year. With about 170 inspectors around the country, WorkSafe has to prioritise.

A more targeted approach focussing on the incidents most likely to result in prosecutions, a change in the way WorkSafe classifies incidents and the impact of Whaakari, which sucked up about 40% of its inspectors in 2019/20, all contributed to the declining number of investigations, Hargreaves says.

But while investigations are down, WorkSafe is carrying out more workplace assessments and issuing far more notices for breaches than in 2016.

And what about the withdrawn charges?

Hargreaves says WorkSafe might withdraw charges for a number of reasons, including in the context of plea negotiations. Prosecutions often include multiple charges, he says, so a withdrawal doesn’t necessarily mean a case has been dropped altogether.

WorkSafe is confident it has the balance right between education and enforcement, Hargreaves says.

“As with any regulator it must constantly assess the impact of its interventions and consider whether any change in the balance of these is required so we are focusing our efforts in the right places.”

Others are not so sure.

Lawyer Hazel Armstrong, a health and safety expert who has acted as an expert witness in hearings involving forestry deaths, is one of them.

Māori dying in the forests

When New Zealand created its no-fault injury insurance scheme in the 1970s, New Zealanders lost the right to sue their employers for damages. As such, people expect there to be a strong regulator, Armstrong says.

“There’s a trade-off when you give up your right to sue that the regulator has to then enforce standards.

“I think that bit is missing from their thinking. I think they think education is okay. Well of course you have education, but it’s not in lieu of prosecution.”

Prosecuting employers who have breached health and safety laws provides accountability and transparency, she says. It also acts as a deterrent.

And while the high conviction rate is a good use of taxpayer money, Armstrong believes it also shows the regulator is taking too conservative an approach.

“I do not think that WorkSafe is undertaking sufficiently robust investigations that result in prosecutions.

“Particularly where workers are killed at work, there should be some public accountability and the opportunity for the family to get reparations.”

And who is being killed?

Before union leader Helen Kelly died, she charged Armstrong with tallying up deaths in the forestry sector and associated supply chain. Armstrong’s current list stands at more than 50 fatalities since 2014, many of which didn’t result in a prosecution.

“The guys that are killed are Māori, they’re in rural areas and they’ve got very little other choices.”

According to a WorkSafe publication, the rate of acute injury with a week or more away from work is 55% higher for Māori than non-Māori. The regulator aims to have the Māori injury rate at an equal or lower rate by 2025.

Accident figures remain 'really sobering' - Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum executive director, Francois Barton. (Image: supplied)

Accident figures remain 'really sobering' - Business Leaders' Health and Safety Forum executive director, Francois Barton. (Image: supplied)'Stuck in first gear'

Francois Barton, executive director of the Business Leaders’ Health and Safety Forum, says New Zealand businesses and the wider country have never invested more than they are now in health and safety.

Yet deaths, injuries and mental wellbeing issues associated with work remain high.

“It’s really sobering,” Barton says.

To borrow a phrase from the Productivity Commission, he says: “New Zealand health, safety and wellbeing performance is stuck in first gear.

“No matter how much more juice we put into the machine, under the current situation we’re never going to go faster than we are right now.”

Barton describes the mechanics NZ has put in place over the last 10 years, including: the creation of WorkSafe, new health and safety laws, new industry groups and millions of dollars from ACC going to harm prevention.

“We’ve built over the last 10 years the mechanics, but we just haven’t got all the pieces working together yet and I think that’s a broader question than just WorkSafe’s role.”

Health and safety initiatives have focussed a lot on changing worker behaviour, Barton says, but there also needs to be a focus on the nature of work – how it’s configured and designed to make it easier for people to make better decisions and ensure any mistakes aren’t fatal.

Sharing positive lessons about improving workplace health and safety also needs to be encouraged.

Forum members recognise the need for a strong, competent regulator, Barton says, but there’s a range of views about whether WorkSafe has the balance right between education and enforcement.

He doesn’t have any view on whether current prosecution numbers are good or bad, but notes there’s a danger of overreaching and causing directors to focus on their own legal liability instead of making the changes they need to make.

“We need prosecution to be deliberate and to be on issues and failings that are actually instructive for others around what to do,” Barton says.

He also wants to see businesses and WorkSafe make more use of enforceable undertakings, a tool described by WorkSafe as an alternative to prosecution.

The OIA figures show there have been just 35 since 2016. WorkSafe has never been to court over any breach of an undertaking.

Barton says the figure seems low.

Enforceable undertakings typically include compensation for victims, an acknowledgement of failure and agreed upon steps to make improvements.

Hargreaves says WorkSafe can’t influence the number of undertakings as applications are initiated by businesses. The number undertaken is broadly comparable to Australian health and safety regulators, he says.

'Not good enough'

Kelly’s successor Richard Wagstaff, the head of the Council of Trade Unions (CTU), says the union body supported the creation of WorkSafe but has always harboured concerns around its capacity to do the job.

“I think we all would have liked better results by now from WorkSafe,” he says.

“There’s been some good results, but overall serious injury hasn’t gone anywhere, fatalities have plateaued - that’s not good enough.

“We want WorkSafe to step up and do more, and they need more resources to do that.”

Between BusinessNZ and the CTU, Wagstaff says, WorkSafe is being told to do more of everything: education, promotion, regulation and enforcement. The regulator has to make difficult decisions about where best to allocate its limited resources.

According to the OIA release, WorkSafe had an annual legal budget of $3.3 million in 2020/21.

Wagstaff says the CTU consistently lobbies the government to increase resourcing to WorkSafe. The union body has also previously called for a review of the Health and Safety at Work Act.

In a statement (he declined to do a phone interview), workplace relations minister Michael Wood says his focus is modernising the regulations which underpin the act. He has no intention to review the act itself.

The work includes completion of plant and structures regulatory reform, which Wood says will modernise safety regulations in areas accounting for nearly four-fifths of all work-related deaths.

Wood didn’t directly respond to a question asking whether he would commit to extra resourcing for WorkSafe, but did say the government has invested $57m to support the regulator.

What WorkSafe does goes beyond investigations and prosecutions, Wood says. He supports its development as a “modern, insights-driven regulator” working alongside businesses, unions and workers to embed good practice.

BusinessDesk asked Wood if continuing high death and serious injury numbers since the Health and Safety at Work Act was introduced in 2016 was of concern.

Any death is one too many, he said. Ignoring the legislation-specific question, Wood then pointed to the fact that New Zealand achieved a 30% lower fatality rate in December 2020 compared to the 2012 baseline of 2.3 fatal injuries per 100,000 FTE. However, this lower rate has flat-lined since 2014-2016, he acknowledges.

“There is still a lot more work to do and we’re committed to strengthening regulations to keep people safe at work.

“WorkSafe is looking into new ways to intervene, continuing to strike a balance between engagement, education and enforcement.”

Over the coming year, Hargreaves says WorkSafe has identified four focus areas to help reduce serious injury and illness:

- Airborne risks and carcinogens.

- Plant, structures and vehicles.

- Worker engagement, participation and representation .

- Upstream interventions targeting people and companies with influence over health and safety outcomes

The first priority area reflects the fact that an estimated 10 times as many New Zealanders die from work-related health exposure than from acute incidents, Hargreaves says.

Whatever the focus, it’s clear a lot of work is required to haul back the number of people being killed and injured at work.

New Zealand has an embedded culture of poor workplace health and safety, Wagstaff says.

“WorkSafe isn’t resourced to do the kind of turnaround that we need. We need a turnaround.”