The findings of Grocery Commissioner Pierre van Heerden’s first Annual Grocery Report are as close as you’ll get to a punch in the nose from a regulator without finding yourself in court.

In contrast to the Commerce Commission’s perennially cautious market studies, with their hedged conclusions and gradualist recommendations, the grocery report is a ripping read.

Anyone with a few spare minutes, a sceptical view of supermarket operators’ claims to be competitive, and an internet connection should find pages 48 to 53 an eye-opener.

Embarrassing

In short, van Heerden found:

- Far from shrinking, margins on groceries (other than fresh produce) have expanded since the commission’s initial market study.

- A monthly index of suppliers’ prices, produced by Infometrics for Foodstuffs North Island and pumped out to the media, has consistently failed to include the impact of so-called “trade spend” – the impact of rebates, discounts and payments that run to “billions of dollars” annually on the prices its supermarkets actually pay to their suppliers. The report stops short of calling this lying. Let's settle for embarrassing.

- The scheme requiring the big supermarkets to open up wholesale deals for competitors simply isn’t working. The prices of goods offered under this scheme are “usually” higher than they can be purchased for in one of the supermarket operators’ own retail stores.

- There has been no observable change in anticipated rates of return in supermarkets’ own internal business plans, suggesting “profit expectations remain elevated” and that “levels of competition are insufficient”.

Wholesale schmolesale

The findings on wholesale pricing are particularly damning.

“In our analysis we found that as many as 54% of the products offered by RGRs (regulated grocery retailers) in wholesale could be purchased cheaper at retail,” the commissioner found. “This situation worsens when the additional costs to wholesale customers of retailing the products are taken into account.”

Meanwhile, many top-selling products are exempt from the wholesale scheme.

This is either because a supplier has asked to opt out, which is their right, or because the products are “home brands” and are de facto exempt from the scheme because they belong to the supermarket owner.

Van Heerden, a former chief executive at Sanitarium who presumably knows where the bodies are buried regarding the sleight-of-hand tricks that all retailers get up to, has decided to act on this.

Next month, he will start an inquiry into the supermarkets’ wholesale schemes, publishing an issues paper for submissions, with a view to announcing conclusions, likely to be new regulation, by the middle of next year.

This is admirably speedy and decisive, assuming there is not some body of previously undisclosed evidence that the supermarket operators can provide in the meantime to say his first big report-back is wrong.

Is the commissioner right?

There are some signs that they will try.

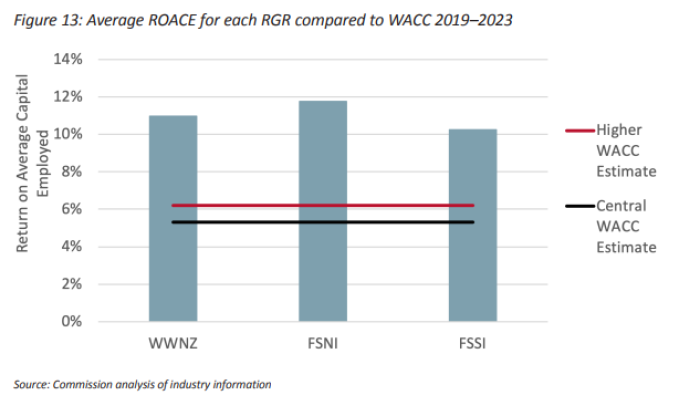

Of particular interest on pages 48 to 53 of the commissioner's report are figures 13 and 14.

Figure 13 compares the sector's average return on capital employed (ROACE), which is between 10% and 12%, with the 5% to 6% weighted average cost of capital (WACC) that the commissioner uses as a benchmark for profitability if the sector were truly competitive.

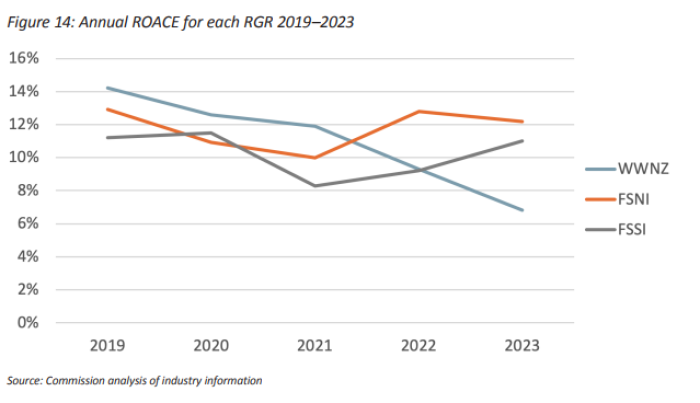

Figure 14 shows the ROACE for each of the three supermarket players – Foodstuffs North and South Island (FSNI and FSSI) and Woolworths.

There is a sliver of good news here for Woolworths, if not its shareholders, since the report shows the former Countdown owner’s ROACE plummeting from above 14% in 2019 to nearly 6% in 2023.

This slide appears consistent with the fact Woolworths' NZ operations reported a trading loss in the latest financial year, which was not available to the commissioner for his first report.

In other words, if supermarkets’ behaviour has changed radically towards greater competition in the past 12 months, that won’t be showing up in averaged, historical ROACE disclosures.

For that reason, van Heerden indicates the two metrics that have underpinned some of the most dramatic evidence of uncompetitive behaviour will now be de-emphasised. They will not even necessarily appear in every annual report because they are “lagging indicators”, and van Heerden would rather use leading indicators.

The report, however, is silent on what those new leading indicators might be.

If he’s not accused of shifting the goalposts, van Heerden will need to be very explicit as to why the measures used to make the case against supermarket competitiveness to date should be replaced.

Appetite for action

The findings are particularly problematic for the supermarket owners because of the wider political pressure for “something to be done” about the lack of competition – real and perceived – in so many parts of the NZ economy.

The prime offenders in the public eye are the banking sector, the electricity market, building products, and supermarkets.

Unfortunately for Woolworths and Foodstuffs, they are the only sector for which any easy fixes look possible.

The Commerce Commission’s report on the banking sector suggests the banks don’t compete because the Reserve Bank forces caution.

The electricity market, meanwhile, appears to have survived yet another near-death experience, with wholesale spot prices falling close to zero this week thanks to heavy rain, wind, and no methanol production by the country’s single biggest gas user, Methanex.

Beyond Shane Jones, there was already precious little appetite at the Cabinet table for pulling the electricity market apart. Now, there will be even less.

Building products remain a hardy perennial problem, although court action against rebates may bring some changes in the fullness of time.

The supermarket owners, however, must now either prove why van Heerden is wrong in the wide range of embarrassing findings he’s made about their profitability and business practices or prepare to be more heavily regulated.