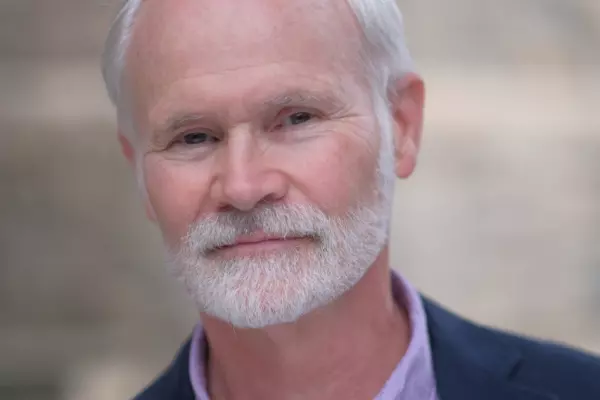

In his new book Comparonomics, former tech entrepreneur, environmentalist and New Zealand government policy adviser Grant J Ryan, who has a PhD in ecological economics, has produced a combination of self-help advice and economics text. He gives up on economics as science to focus on what happens if we allow subjective perceptions to guide our conclusions. It turns out we have been worshipping false financial gods. Ryan spoke to BusinessDesk contributing writer Paul Little.

The first part of your book involves people comparing their experience of things now with how life was in the past. Can you explain how this leads into the rest of the book.

The first part gives people a tool called the comparonomic graph to work out how they are getting on in life. No one likes to read a book that is just experts arguing against each other. I didn't want to be saying your life is better. Inventing that tool was the key. Most people, when they do it, get a different result from what they thought. They are actually doing better than they think they are. The point, then, is to prompt them to ask why they don’t feel so good.

The second part is a list of well-researched but not well-known reasons we don’t feel better, such as digital screen addiction, or the cultural expectation of constant happiness, or the impact of advertising and a tendency to remember bad news but not good. And the last part is about how we could do better. I look at the common things governments on both the left and right do about problems and find they don’t make that much difference, and then I pose some solutions.

What are the implications on a broader scale?

Everyone knows how poor economics is at assessing the things that matter to us, such as individual happiness, but they don’t know how poor it is even at measuring economic things. I got frustrated because I saw so many people doing things that wouldn’t make much difference. I'm a greenie at heart and climate change is eminently solvable by allocating some resources that aren’t that much on the great scale. But if you come from a place of doom and “we can’t afford that”, then you won’t try.

You don’t spend much time on green issues as such.

No, because there are a lot of things – not just green issues – you can do something about with this mindset. The idea is to get people to understand the reality of how the world works. When you understand that you are on a treadmill, you then have permission to step off.

How did your concept of how things work come about?

At the time I did my PhD, ecological economics was considered completely hippie. I was worried about pollution and running out of resources, but I came out of that research more optimistic. I worked out that the world is finite. We are not all going to have flying cars, because of physical limitations. But there are lots of things in the economy that are not physically constrained, like education, entertainment and health. Over 30 years, I was observing these things and how poorly economics measured them. To take one example: you used to have to be rich to own an encyclopaedia. Now it’s free on your laptop and probably 100 times better. I had to save up to buy a cassette when I was a kid. Now I can get that music free on my phone.

How bad are the things that make us feel bad?

They are completely ingrained. I fall for them, too. It’s funny when you are aware of these things. When I talk to people about the book, many will tell me that what is in it doesn’t relate to them. They say: “It doesn't interest me. I am completely happy with my life.” And within an hour they will be bitching about the state of the world and how good life was in the old days.

You lead up to talking about “status-ism”, which has an interesting definition: “Prejudice … against someone of a different social status based on the belief one’s own social status is superior… The belief that all members of each social status possess characteristics … specific to that social status.” You spend a lot of time analysing how it works. Is this what the book is really about?

When I was doing it, I assumed I would find that equality would make things better. I was genuinely surprised it didn’t make much difference to many of the feel-bad factors I described. I was thinking: what does? Being aware of them does. A lot of our pangs are about seeking status. How do you solve that? Not everyone can be at the top, so why do we bow down to someone at the top, whether it is because they are good at rugby or are rich? That is when the analogy to racism or sexism is clear. There is a subsection of the population we choose to treat differently because of their social status. And that’s not good.

Status sounds awfully like class. Does it not actually describe the same divisions? Yet you compare such terms as “working class” and “upper class” to derogatory terms for women or people of colour. Surely you can’t make classes disappear by not using the words?

I talk about income, not class. With status-ism, some people assume that your income says something about your value. We all know rich people who are plonkers. What you earn has nothing to do with who you are as a person. When you talk about “the middle class”, you are assuming that this set of people is better or worse than you.

I’m guessing you are a pretty upbeat kind of guy. Is there anything economic that worries you?

The housing crisis is a crisis. It is embarrassing to have homeless people in New Zealand. And it is solvable. We all have expectations of owning a type of house that actually isn’t possible for all of us. It’s often pointed out that housing is cheaper in Europe, but the housing is very different. Even in small towns, people live in apartments. It does my head in when people say Auckland is more expensive than London. An Auckland-style house in London? Forget about it. We have to get used to living in apartments.

Another thing that worries me is tax. Once you earn a certain amount, you have the opportunity to send it overseas to tax havens. The only possible reason to do that is to somehow be in a slightly better position within the 1% and be associated with drug lords and criminals. Do you want that? Why not just pay a bit more tax and contribute to solving problems like mental health and child poverty. It’s a no-brainer.

How do you think economists will respond to the book?

I think most economists probably won’t like it at all. I would like to emphasise that I don’t want to throw things like GDP out the window. It is fine going quarter to quarter, because things are the same over those periods. But it is no good over the long term. The Comparonomics method shows that when people write saying that this is the first generation in history where children are doing worse than their parents, it is just bollocks.

Comparonomics: Why Life Is Better than You Think and How to Make It Even Better, by Grant J. Ryan, Big Idea Publishing Company, $29.99