The confident careerist wins the day, correct? Don’t be so sure. A surprising number of high achievers are convinced they are the wrong person for the job. They can even sabotage their progress with self-doubt, or carry their insecurity into a role when they get it. And imposter syndrome is so widespread that people who don’t have it are probably starting to pretend they do, just to fit in.

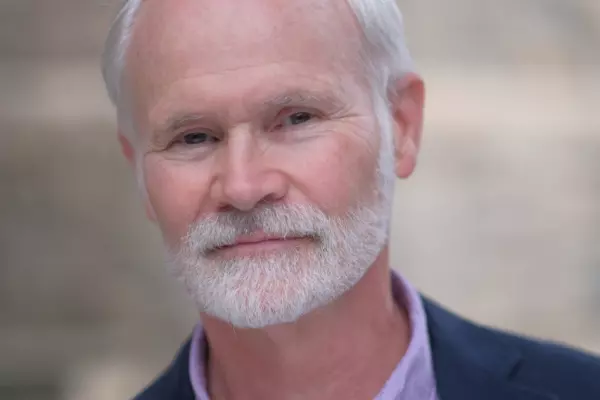

Just ask Tom O’Neil, managing director of career coaching consultancy cv.co.nz, which has worked with more than 12,000 clients from all around the world.

When he was 26, having started his own recruitment co and then successfully sold it, O’Neil saw an advertisement for a job as an HR management consultant with one of the big four accounting firms. One of his own referees had already been turned down for the role. O’Neil was sure he wasn’t right for the job, so didn’t apply. But when he saw it readvertised, he threw his hat in the ring, and “even though my self-belief was zero”, he won the post.

“I started the role and found that they had forgotten to put in the job description and the advertisement that there was a sales role and an HR role. All the senior HR managers around the country lacked consultative sales skills, so that's how I got the job. But I couldn't believe I was there on my own merits, until I was about six months into it.”

Which makes O’Neil well placed to deal with people in senior positions who suffer from self-doubt. He has used his own experiences and those of his clients to work out where self-doubt comes from and what can be done about it.

“A large proportion of our clients are executives wanting to market themselves, but many of them are useless at talking about their own achievements. People are Ferraris, and they sell themselves as Toyotas. My experience working with people who've done really well is that they are not aware of why they've done really well. Part of my job is to help educate them about their own value. I developed a tool called the O'Neil Major Achievements Questionnaire that helps a person quantify their achievements.”

So successful was the questionnaire that it has been included in the world's best-selling career guide, What Color Is Your Parachute? O’Neil has also been published in the Harvard Business Review.

He says people don’t need to exaggerate to overcome self-doubt. It’s all in the way you tell it.

“You can say, ‘In my last job I was operations manager and managed lots of staff.’ Or you can say, ‘I managed 214 staff for seven direct reports and was in charge of a budget of $4 million per annum, guided a new warehouse system and implemented a new updated SAP program worth $2 million.”

How can anyone else understand what an executive is good at if they themselves don’t know? “It’s critical to understand the value that you can bring in a tangible way. I can say to you, ‘I've got really strong IP.’ But if I say, ‘I've been published twice in the Harvard Business Review around career leadership,’ suddenly that creates a strong impression.”

Career coach and consultant Tom O'Neill.

Career coach and consultant Tom O'Neill.

A little bit of bravery can help you go a long way. O’Neil says people often give way to self-doubt if there are, say, 10 requirements for a job and they have only seven. He points out that the remainder are likely to be things that can be learnt once the job is started and another can be learnt only on the job.

“At every job you move to, there will be a disconnect,” says O’Neil. “That's the point. Why would you apply for a job that is the same as what you’re already doing? The whole point of it is to be a challenge.”

He adds that past negative comments, going back to those from teachers and parents, can continue to do damage years later. “People have an internal dialogue that says, ‘You're a failure. Remember what Steve, your old boss, said. You'll never amount to anything.’ And we tend to listen to these voices and that cripples our potential. So it is important to have a true and honest voice about you and what you can do.”

Which means that sometimes we need to give ourselves a good hard talking to. Even O’Neil is not exempt from this failing. “We've done more than 12,000 CVs and career solutions for people all around the world. But if I get one person emailing me going, ‘I don't like the font’, my whole world falls apart. It's crazy”

It is one thing to be promoted from manager’s assistant to assistant manager. It’s quite another to be given custody of an institution as venerable as the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, founded in 1932. The magazine’s editor, Marilynn McLachlan, has gone from print (New Idea) to digital (Urban List) and back to print. She says self-doubt hasn’t been a problem, but that’s not to say she is unaware of the issue.

“When I took on this job, I was so excited about becoming the editor of a national treasure,” says McLachlan. ‘It's celebrating its 90th birthday this year. Amazing women who I've looked up to in the past have been its editors.”

But that first excitement doesn’t last forever. “Once you’ve been a little bit in the job, you question yourself a lot. There's a huge responsibility that comes with this.”

Marilynn McLachlan, editor of the New Zealand Woman's Weekly.

Marilynn McLachlan, editor of the New Zealand Woman's Weekly.

Support from peers and those further up the hierarchy has been crucial to keeping doubt at bay.

“My boss was very good at guiding me. ‘Back yourself, Marilynn,’ she said. ‘You've got this.’ And that really makes a difference. The other thing I did quite early on, and still do even now, is talk to other editors of magazines and newspapers, male and female. And I would say every single one, without a doubt, could relate to how I was feeling.”

Support from everyone in her network has been there from the start. “I had really supportive parents who were both career people. There was an expectation to do well, but no pressure. They always put a big focus on education.”

Self-confidence doesn’t mean no worries. There are still things that keep McLachlan awake at night. “It'll be something really small, like a date in a story. Did I get that right? Or did I get the person’s age right?”

Self-doubt is also a sign that someone cares about what they are doing. “If you didn't worry about things, then you probably wouldn't care,” says McLachlan. “Most of it is that you just want to get things right. And you set such high standards for yourself, but even if you are aiming for perfection, it probably isn't possible.”

A final word to the wise that McLachlan has followed: keep going. “My mentor said to me at the beginning: if you do this, you must do it for one year. Make a decision after that, but you must do one year. So I always had that in my head. I thought that was a really good piece of advice. And I’m coming up to two years now.”