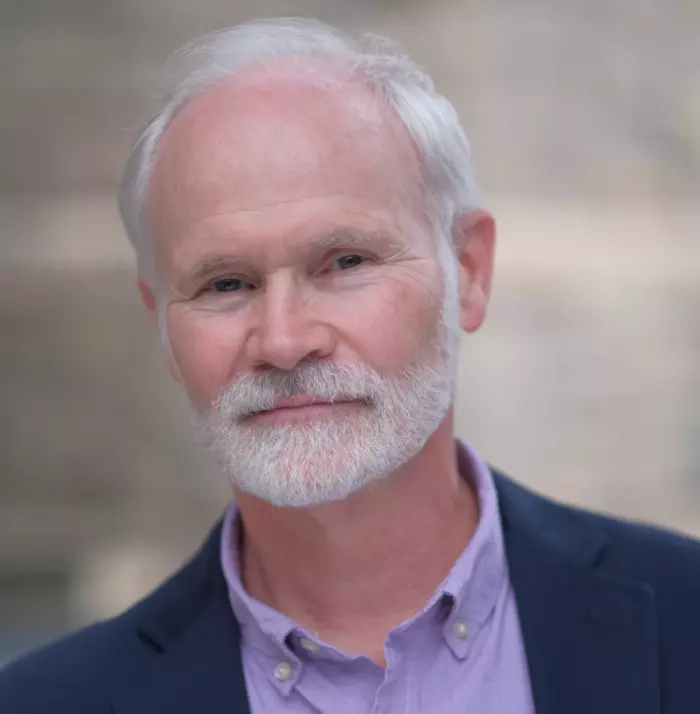

Dr Nate Zinsser runs the performance psychology programme at West Point military academy in upstate New York. In more than 30 years there, he has not only helped to train cadets for the battlefield but also inspired elite athletes to success in the Super Bowl, Olympics and many other events. He shows them how to use mental toughness and self-belief to master confidence in any field, and now he has put his methods in a book, The Confident Mind: A Battle-Tested Guide to Unshakable Performance.

Anyone reading this will want to know what the world-famous West Point is really like. The general impression is probably one of a lot of shouting and a lot of grey.

There is a lot of grey. The buildings are grey stone. The cadets often wear a grey uniform. And for many months of the year, the sky is typically grey. It's as cold as hell around here. The yelling? Not so much any more. While discipline is absolutely practised, the idea now is to develop people rather than just filter out the ones that have the right stuff. The whole institution has become a little more developmental focused, rather than just based on a model of attrition. If someone fails a fitness test, they will be given the chance to make it up. We will bring resources to help them develop the needed skills. We wouldn't let them in if we didn't think they could handle it.

Has it changed much in the time you have been there or is it resistant to evolution by its very nature?

The institution has changed tack. Women were not admitted into West Point until 1976. And because there are women who wish to serve in the army, the officer corps has to be reflective of that. So there's been a big transition in terms of gender and racial and religious diversity throughout the army, including at West Point.

What do you tell people when they ask you what your book is about?

I tell them it is a manual for how to understand what confidence is, how to build it up, and then how to put it to use when you need to.

And what's your personal experience of this? Have you used your strategies on yourself?

It goes back to why I got involved in the whole sport psychology field in the first place.

And that was because I was a competitor myself as a young man. I wanted to become as good as I could be in various sports. And it became clear to me at a young age that it was more than physical. Nowadays, in terms of maintaining my performance, I try to practise a lot of what I put in the book, especially maintaining the right kind of constructive mental dialogue with myself.

Do these rules also apply to your professional life?

Oh, absolutely. I work at a big institution that has a considerable bureaucracy. And I've got to learn to roll with those punches and make sure that I don't take setbacks personally. I have to protect my own sense of certainty about my ability to get things done, even when there are lots of obstacles in the way.

What you're saying there is that even having the right kind of confidence doesn't guarantee success, does it?

All the confidence in the world does not guarantee success. But it really improves your odds somewhat. And it's something that you can do to maximise your odds. Other things, of course, are going to influence success. As we say in the army, the enemy also gets a vote. You still better have maximum confidence if you're going to react and respond as well as you possibly can. But it's something that everyone can do, regardless of circumstance. That's the whole point of the book.

This isn't just for the top one per cent – it's broader in its applications?

We're not just talking about what world-class or Olympic-class athletes have to do. I think it matters so much to people who are working a nine-to-five job and just trying to do as good a job as they possibly can.

There's a phrase you use about something that builds confidence that I was intrigued by: creating an attitude of “energetic curiosity”. How does that work?

It means: Let's see how well I can do this. I can do it in this practice, but let's see how well I can do it in the game. If we're entering the fourth quarter, or the final innings, or the final set of the tennis match, let's see how well I can do now. And when you unpack that statement, there are some implications. The implication is that I can do well; it's only a matter of how well I do. And it's a matter of allowing myself to do as well as I can do. So that's what the curiosity is. Let’s go into this with inquisitiveness rather than having a predetermined outcome in mind, which for most of us tends to be negative.

Are there people who are naturally confident?

I've met a few. There are plenty of high performers at this institution. They've made the adjustment from high school, to the college, to the university, to the military academy environment without too many setbacks. I don't know if they have always been functionally confident. But confidence is not really a genetic disposition that you're born with. It's really a quality that you develop over time.

What's something useful you've learned from someone you have worked with?

I think back to something that one of the captains of our teams shared with me many, many years ago. And it was simply the fact that he, as the captain of a large team of young men, had to act as the enforcer, the disciplinarian. It wasn't something that he necessarily liked to do. But he knew it had to happen. At the same time, he had to make sure there was another person who could be the one who kept things a little bit loose in the locker room, who could crack a joke and could make players feel at ease. So what I learned through that is that leadership takes many different forms and that not everybody in the unit has to be all things to all people. You've got to have all of those elements within the team.

And from your point of view, in your field, what's the best thing about working at West Point? What has it done for you?

All 4000 men and women who are here volunteered to come. It wasn't a place where they had to go. They could have gone to their state university, or in many cases to Harvard or Princeton or MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology]. But they wanted to challenge themselves with something bigger. If you come to West Point, you're going to get a good education, but you are also going to serve in the army as a leader for a minimum of five years upon graduation. So there is a commitment to something bigger than you have in any civilian school, whether it's a public institution or a private institution.

Five confidence-inspiring tips from Nate Zinsser

- Confidence + competence = success.

- Develop a mental filter to shut out negative experiences and allow your mind to focus on positive memories that will influence success.

- Envision completely and vividly how you want that breakthrough to unfold and how you want to feel, then when the opportunity presents itself, you feel like you’ve already done it and done it well.

- Embrace feeling “nervous” – this is your nervous system being more active. The result of all this activity is that you become stronger, faster, more alert, more perceptive, more prepared to take on the world.

- Forget perfectionism. Compulsive striving toward impossibly high standards, and the simultaneous self-criticism and negative judgment, undermine confidence.

The Confident Mind: A Battle-Tested Guide to Unshakable Performance, by Nate Zinsser, Cornerstone Press, RRP$40.