The world record for folding and unfolding a Brompton bicycle is 21.04 seconds.

There can’t be many cycling records the distinctive Brompton folding bicycle, with its 16-inch wheels, is likely to feature in, but it says something about the loyalty of the brand’s fans that googling “Brompton folding world record” throws up 1.36 million results in 0.42 seconds.

And, as it turns out, there is at least one other record: Land’s End to John O’Groats in 83 hours.

That’s right; a mad bugger by the name of James Stannard, who heads up research and insight at Brompton, to be precise, rode the length of Britain – 1,415km – in under four days.

That beat the previous record of five days and 15 hours by than two days.

My own efforts on a Brompton, borrowed from Wellington’s Bicycle Junction, were less ambitious.

Folding up the Brompton set me back by a few minutes rather than seconds, with a quick YouTube tutorial required to get the technique right.

It’s an ingenious and remarkably straightforward exercise once you’ve got the knack. More paper dart than origami dragon.

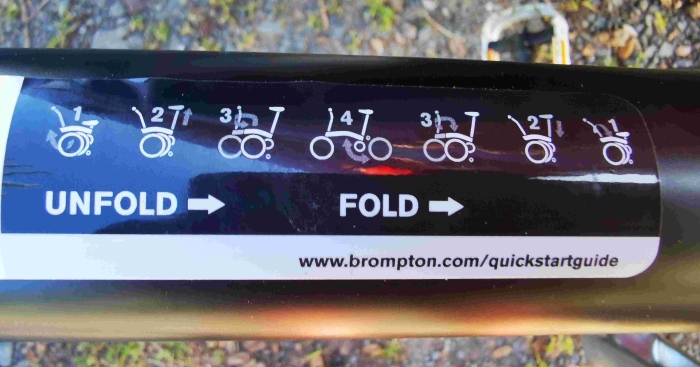

The back wheel folds under the frame, the extremely long seat-post slides down behind the back wheel, the front end then pivots around to join the back wheel, the handlebars flop down, and finally the left-hand pedal flips over and you’re left with a tidy square package.

There’s a handy diagram (below) on the bike’s main tube should you need reminding of the order.

Brompton enthusiasts – and there are many – swear you can fit the folded bike into an plane’s overhead locker, which feels a tad ambitious to me. And, in any case, at 12.1kg, it’s heavier than allowed by Air New Zealand.

But taking it as standard luggage would still be a lot easier than disassembling and boxing an ordinary bike. And taking it on the number 14 bus from Roseneath to Wilton was a breeze.

Wellington’s buses are now equipped with front bicycle racks but they’re not always available, and it’s hard not to feel slightly guilty for delaying the bus when loading and unloading your bike.

Boarding with the Brompton was no more of a hassle than taking a bag of shopping.

I jumped off the electric bus a couple of stops before my destination – the Otari Native Plant Reserve – unfolded the bike (just like folding in reverse) and rode the short distance to one of Aotearoa’s natural taonga.

The bike’s narrow handlebars and small wheels give the Brompton a lively feel – not unlike that other small-wheeled British bike, the Raleigh 20.

The bike rides surprisingly well considering its relatively tiny wheels.

The Brompton's design – with its 1200 individual parts – has changed little since it first went into production in the mid-70s.

One of those parts is a rubber block that, when the bike is unfolded, sits between the back triangle and main frame, providing a welcome degree of suspension.

It helps to smooth out what otherwise could be a jarring ride due to those 16-inch wheels.

I travelled back into the city down Glenmore St. When I ride that road on my commuter bike, I usually take the lane and travel at around the 50km/h limit, but on the Brompton I stayed to the left and travelled at a more sedate 30km/h or so. I worried that if I hit a pothole I’d go flying.

The first real climb on my return journey was the road up to Roseneath from Oriental Bay.

The Brompton comes in a few different configurations – including an electric version. I had the six-speed with a 300% range.

First gear was plenty low enough to tackle what is a fairly typical Wellington hill. But the choice of a three-speed internal hub paired with a two-sprocket derailleur setup is an oddity. To travel evenly up through the gears requires a dance of the thumbs selecting 1st, 2nd or 3rd with your right hand and switching between minus and positive with your left.

At first, I assumed it was because the proudly British Brompton was determined to use only locally made parts, and the three-speed Sturmey Archer hub was the only thing fitting the bill.

Otherwise, why not simply use one of the 7-, 8-, 11- or 14-speed hubs made in Japan or Germany? That would have the bonus of allowing a belt drive to the setup – both cleaner and more durable than the traditional chain.

But it turns out that Sturmey Archer has an 8-speed model with a similar range to that achieved by Brompton.

It’s a mystery to me why they’ve chosen what seems to be a sub-optimal set-up. And I’m not alone. There’s an outfit in the UK offering a conversion kit that allows you to fit a Shimano hub and belt drive to a Brompton.

Even the pedals can be folded back so they don't stick out on the bus.

The Brompton would be perfect for those wanting to catch rush-hour public transport with their bike, for regular inter-city travellers who want to have a bicycle at either end – taking it on a plane as luggage would be far less hassle than an ordinary bike – and for inner-city apartment dwellers without garaging, who could park it up in a wardrobe.

At $3,795, it’s not cheap, but its remarkable portability and the ease with which you can jump on a bus to tackle Wellington’s many hills means it’s not only a commuter-bike alternative, it’s an e-bike alternative, too.

It’s the best of British industrial origami, and for those who find a full-size bike a hassle, it provides a brilliant solution.