Don’t skite. Stop showing off. Don’t go on about yourself. US author and entrepreneur Meredith Fineman has written a book devoted to the notion that these well-worn pieces of advice are not just wrong, they’re harmful. Brag Better is a highly practical guidebook full of advice on how to get your light out from under the bushel, particularly in the workplace.

It’s aimed primarily at women, for whom the problem of how to self-promote positively is endemic, although men can suffer from it, too.

A lot of people react negatively to being advised to brag at all.

“When I saw your email about an interview, my immediate reaction was, he thinks I’m a bragger, and that made me feel uncomfortable,” prominent Auckland social entrepreneur and independent director Victoria Carter told me. “In New Zealand, we often do see people who talk a lot about themselves as being arrogant or insecure.”

Even Fineman took a long time to get comfortable with the B word. “People told me not to use it,” she says. “I looked for a different word to describe the activity of talking about professional accomplishment – ‘tout’, ‘hype’. None of them got at what I was talking about.”

Brag Better author Meredith Fineman

Brag Better author Meredith Fineman

One of the key messages is that “bragging is simply stating facts”, telling and showing people what you’ve done, because otherwise they won’t know. She’s lately had to alter this to “true facts” to distinguish them from the other kind, which have become so common in recent American discourse.

Locally, Loretta Brown, director and lead coach at the New Zealand Coaching and Mentoring Centre, talks about “a concept called healthy ambition”. The “healthy” is necessary, she says, because for many people, even “ambition is a dirty word, suggesting people trampling on each other to get up the ladder. Healthy ambition is not self-serving; it’s about having a platform and making an impact in your role.

“I have examples of women who will be kept in their roles by male bosses because they are ‘doing such a great job’,” says Brown. But women can also be complicit in efforts to stifle their healthy ambition, saying they “work better behind the scenes” or “don’t like being in the limelight” or are “great in a 2IC role”.

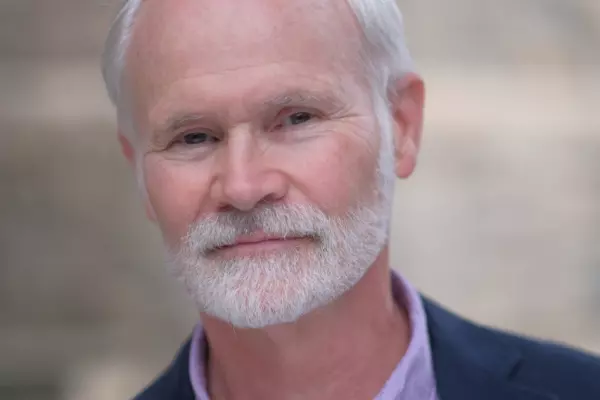

Coach and mentor Loretta Brown

Coach and mentor Loretta Brown

No one’s denying there are men who also have the problem, but “my view is that women often don’t take credit for their achievements, let alone exaggerate them”, says My Food Bag co-founder and former Telecom chief executive Theresa Gattung. “If a woman tells you she did something, or that she founded and sold her business for a certain amount, it tends to be true.”

She also recognises problems with vocabulary: “Brag does sound swaggering – it doesn’t have a nice feel, and women leaders still run a very fine line being seen as strong enough but not too strong. Men don’t have to worry about that.”

Gattung never had any doubts that she should be taken seriously as a woman in business or any other sector. She is the eldest of four daughters, and her father had five sisters.

Theresa Gattung

Theresa Gattung

The problem is probably most visible in the corporate meeting room, where women can struggle to be heard at all, let alone get in the odd brag.

Carter has seen it many times herself and is now getting reports from the next generation, a member of which, she says, recently “said to me that all the time she is thinking, ‘I have to be extra friendly, extra bubbly, don’t be a bitch.’ And men continually talk over the top of you. Even when we are the more experienced person, we will be interrupted. Men don’t get told off for interrupting; we get told we are bossy.”

Bragging can be a team sport, with people bragging on each other’s behalf. “Women could do a better job of promoting each other,” says Carter. “Each generation will be that much better at doing these things.”

This echoes Fineman’s view: “It’s part of your job to share and pass the mike. It’s not just about you.”

A form of bragging that’s particularly hard for many to carry off is the brag about why you deserve more pay.

“When I work with women, they believe they deserve the money but don’t know how to ask for it and are crap at negotiations,” says Brown. “All it takes is a little bit of planning and role-playing and they get it and get the results. It is a little tweak.”

According to Fineman’s philosophy, by the time you get to the negotiation, you’ll have been bragging so well about your skills and achievements that the boss will know exactly why you deserve more.

Without pay transparency, says Gattung, it’s hard to know what to ask for. Furthermore, “women expect to be treated fairly and find it quite difficult to put themselves forward for money”.

Victoria Carter

Victoria Carter

Even as experienced a businesswoman as Victoria Carter has to fight against the pressure to blend into the background. “I’ve been self-employed since I was 24 and I’ve had to hustle all the way,” she says. “But I don’t see brick walls, and thank God I don’t or I’d get flattened.

“It doesn't always feel comfortable, but if you want to get the work, you have to put yourself out there. I was on a plane to Wellington the other day and saw a man I recognised whose radar I wanted to get on. If he was going to be looking for someone with my skills, I wanted him to know I’m here.”

But Carter didn’t feel comfortable about approaching the man directly on the plane. “So, I waited till I got home, opened up LinkedIn and wrote a friendly note and ended up having a Zoom meeting with him. Those are the things we have to do.”

But where do you start? Are there baby steps on your way to conquering corporate timidity? Indeed, there are, says Meredith Fineman, and they don’t have to involve scary person-to-person contact. “There are opportunities everywhere for you to promote yourself. It doesn’t have to be big. It’s not about changing yourself. Its 100 percent working with what you have.”

She says a first step is to look at your email signature, a great location for information about yourself.

“If someone has nothing in their email signature, should I have to open a browser, google them, deduce what they are talking about?” Instead, tell people who you are right there at the end of the email. And include your phone number: “Some people might need to talk to someone really quickly and want to get on the phone.”

Fineman also recommends LinkedIn as a place “where people expect you to talk about yourself”. That’s a good home for your professional biography, which should come in three versions: full, paragraph and two sentences. And if you update one, don’t forget to make the others reflect that. “A lot of people miss this. Write your bio and update it regularly. It can be in chronological order, or in order of what is important to you.”

And include everything in the full one. “I had a client who left out all these awards – she thought it was a bit much. But people at this point are primed for your bragging, so there are no judgments being made.”

Not being judged. Wouldn’t that be something to brag about?