American cooking teacher Julia Child famously said, “I enjoy cooking with wine. Sometimes, I even put it in the food,” which is an appropriate way to introduce the topic of wine and food pairing.

I clearly remember the first time I appreciated just how a splash of wine could enhance food flavours. I had recently joined a winery (Montana Wines, now Brancott Estate) as an accountant and was desperate to unravel the mysteries of wine. I eagerly accepted an invitation to dine at the home of a person I regarded as a “wine expert”.

The host poured us all a French chardonnay, Drouhin Clos des Mouches. It was absolutely delicious – the best wine I had ever tasted at that time. For an entrée, he planned to cook plump, freshly gathered scallops. When these were nearly ready, he shocked us all by pouring half a cup of Drouhin Clos des Mouches into the sizzling pan just before serving them. The scallops tasted fantastic. They echoed the flavour of the wine. The combination was devastating.

I was recently asked to recommend a good wine to use when cooking. If it is intended to flavour the food, it is a good idea to use a wine that you would choose to enjoy with the dish. For example, chardonnay is a good match with scallops, I like a dry rosé with smoked salmon, pinot noir generally goes well with duck breast, and syrah is a winner with most lamb or beef dishes.

When I cook, I like to have a glass of wine close at hand and generally choose the wine I plan to serve with the food. I justify the “chef’s glass” as a trial run to get the temperature right and to see whether the wine needs aerating, in which case I will slosh it into a decanter. If the temperature needs adjustment, it is a simple matter of putting it in the microwave or fridge.

Wine and food matching is a popular topic in my wine course. I use a practical tasting to get the main points across.

First, I pour a slightly sweet riesling and invite the students to taste and assess the wine. If I have chosen well, the first impression they get is a sensation of slight sweetness. That is quickly followed by a heightened sensation of acidity, particularly on the sides of the tongue.

Now I ask everyone to eat a small slice of apple and taste the wine again. Does the apple make the wine taste sweeter, drier, or no change? Usually 100% will say “drier”. The sweetness in the apple pulls down our perception of sweetness in the wine, which becomes more acidic.

The take-home message: If you wish to match a wine to a food that has sweetness in it, choose one that is sweeter than the dish. You will get a better match of sweetness in both the wine and the food. If you choose a wine that isn’t at all sweet, the sweetness in the dish could make it taste unpleasantly bitter.

Next, I invite everyone to lick a small slice of lemon and retaste the slightly sweet riesling. Is it sweeter, drier, or no change? Everyone votes for “sweeter”. The acidity in the lemon pulls down our perception of acidity, making the wine taste sweeter.

The take-home message: If you need to match a wine to a food that has prominent acidity, choose a wine with plenty of acidity. If you choose a soft, low-acid wine, it could become bland. (My wife usually can’t drink sauvignon blanc because it is too acidic, but once, when I gave her a piece of fish garnished with a squeeze of lime, the apparent acidity in the wine dropped and she was able to enjoy it.)

On my wine course, I follow that by pouring everyone a glass of big, astringent red such as cabernet sauvignon. We taste it and discuss its characteristics. Some students usually find it to be excessively astringent.

This time, I give everyone a cube of creamy cheese – I usually choose white Castello. Now I ask them to eat the cheese and taste the wine again. Do they like it better with or without the cheese? Most prefer it with the cheese and express surprise that the red wine has become significantly less astringent.

The take-home message: The uncoagulated protein in the cheese wraps around the tannin chain and smothers some of the wine’s astringency. Most people like it better that way. Cheese also turns down the volume of the wine, which some find less appealing.

The take-home message: If you are wondering what to serve with an excessively astringent red wine, choose a food that is high in uncoagulated protein, such as a rare steak rather than a well-done steak.

When we make a strong cup of tea, we can dampen the tannins by adding milk, which is high in uncoagulated protein. We can also add a squeeze of lemon, which cancels some of the tannic acid, making the tea taste softer and less astringent.

Whenever I am enjoying wine and food, I ask myself if the wine improves the taste of the food and if the food improves the taste of the wine. Then I try to figure out why.

Bob’s Top Picks for sipping and cellaring

Investment Wine

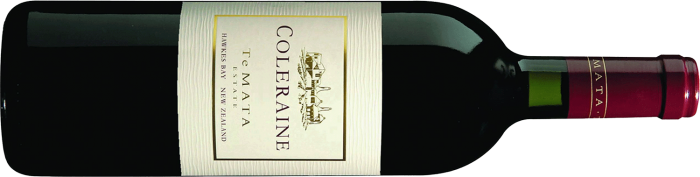

2020 Te Mata Coleraine, Hawke’s Bay, $115

A blend of cabernet sauvignon (57%), merlot (36%) and cabernet franc (7%). Deeply tinted, almost inky wine with layers of sumptuous fruit and savoury characters, including cassis, red rose, dark chocolate, hedgerow, anise and nutty oak. A generously proportioned, youthful red that is already surprisingly accessible but promises to age gracefully.

Weekend Wines

Top White

2019 Greywacke Pinot Gris, Marlborough, $32

Greystone consistently makes one of the country’s best pinot gris. This is a rich, ripe, almost luscious wine with an appealing mix of ripe pear, apple and bready yeast lees flavours. Good weight and a lengthy finish.

Top Red

2020 Auntsfield Pinot Noir, Marlborough, $45

Deeply scented pinot noir with cassis and floral/red rose leading to similar flavours on the palate together with dark-fleshed plum, dark cherry and spicy, smoky oak. Impeccably balanced wine that can be enjoyed now but promises to deliver more with bottle age.