“List, list, O, list!”

Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act I, Scene 5

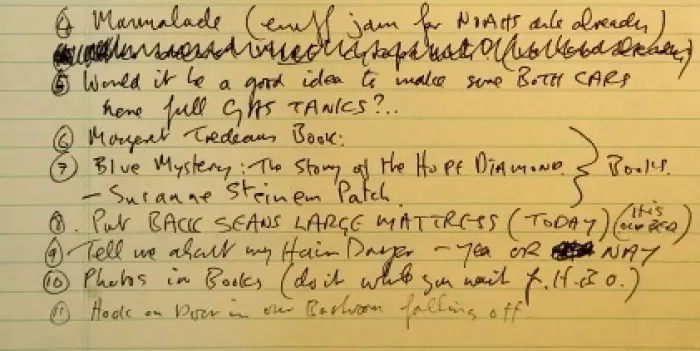

To be honest, the Bard was using the word in a different context, but that despairing cry uttered by the ghost of Hamlet’s father could easily find a contemporary echo. Increasingly, many of us are letting lists run our lives. From our work diaries to our Netflix “My List” pages to year-end, best-of round-ups in the media, the lists are endless.

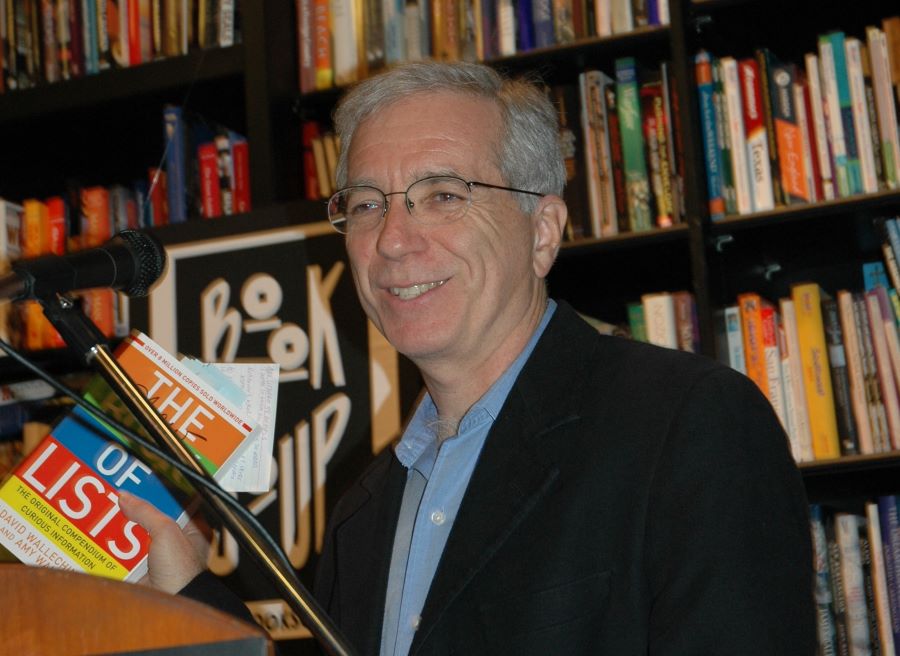

Not many people know more about lists than prolific author David Wallechinsky, who in 1977 kick-started “listmania” (as we know it today) with The Book of Lists, co-authored with his father, Irving Wallace, and sister Amy Wallace. It was followed by numerous sequels and the list-heavy, encyclopaedic People’s Almanac. They were kind of like the internet, but books.

“I remember when Wikipedia started and one of the first entries for the People’s Almanac and the Book of Lists said, ‘This was a precursor to Wikipedia.’ I considered that an honour,” says Wallechinsky.

Accurate, too. Even the kinds of lists he pioneered are the default today. “I definitely early on tried to include serious and not-serious lists in most books. Most other lists at the time were one or the other. That was good, but for the People’s Almanac, we had bios of famous people, but also footnote people – names that only get a footnote normally but were, to me, important.”

Lists have been good to Wallechinsky, but he doesn't let them rule his life. He doesn't hanker to be on a rich list. He doesn’t even have a bucket list. “I get it, but it doesn’t interest me,” he almost snorts. “If there’s something I want to do, I’m going to do it. I don’t have a list.” As for being on the A list, “Who cares? It’s just a word that says something that already exists.”

Nor does he lay claim to being the first person to produce a book of lists. In fact, he is the owner of one produced 300 years before his own. “It’s called Wonders of the Little World, by the Reverend [Nathaniel] Wanley.” But he will accept some responsibility for popularising the idea. And he thinks he knows why we like lists so much.

“They have become more popular. Nowadays, the reality is that we live in a very complex time and we are overwhelmed by information and now disinformation. So it’s a way of getting a grasp on something. If you can reduce it to [a list of] 10 or 7 or 100, it seems more graspable and less intimidating.”

Author David Wallechinsky is an expert in the psychology behind lists.

Author David Wallechinsky is an expert in the psychology behind lists. And then there’s the to-do list. One of the first people to study lists seriously, rather than to just compile them, was Lithuanian-Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, who nearly 100 years ago identified what has come to be known – in some circles, anyway – as the Zeigarnik Effect. In brief: we remember incomplete tasks more easily than tasks that have been completed.

Consequently, once we have ticked something off a list, it exits our brain, freeing up space for the things we still have to do. So the mere fact of making a list starts us subconsciously working on the items on the list and therefore getting a result faster.

Lists are also easier to understand than other ways of presenting information because they:

- Can be arranged neatly into bullet points.

- Take less time to deal with because they tend to be short.

- Are easier to understand than complex, nuanced narratives.

- Appear to be definitive – a list is by definition complete. Lists are finite, not open-ended.

Lists can also be economically powerful. In Auckland, Metro magazine’s annual top restaurants and best schools lists – even though such claims are barely quantifiable – are two of its most popular features, bringing bounteous rewards to hospitality and educational enterprises alike.

International university rankings, for example, can affect people’s decisions about where to spend tens of thousands of dollars in fees. Although there are serious questions to be asked about their criteria and methodology, the results of these rankings are key parts of universities’ marketing.

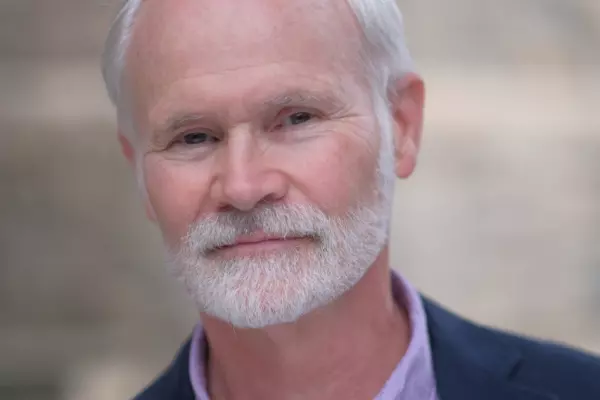

Mathew Isaac, professor of marketing at Seattle University. Photo: Seattle University.

Mathew Isaac, professor of marketing at Seattle University. Photo: Seattle University.

Mathew Isaac, professor of marketing at Seattle University, has looked into the list-making phenomenon in depth, particularly as it relates to university rankings. He is the co-author of The Top-Ten Effect: Consumers' Subjective Categorization of Ranked Lists, published in the Journal of Consumer Research, and has some fascinating findings about how we use lists to make decisions, and which numbers matter.

He has made a close study of US News and World Report’s regular lists of college rankings. “We know they impact applicant decisions as to where they will consider going,” says Isaac. “I was curious to understand how people convey information from the lists to evaluations – how does knowing that a university is ranked number 8 on some list, against number 11, affect things? That is what the top-10 project was about.”

Isaac says how we rate things on a list is not just about where they come in sequence. We make clear demarcations at certain points.

“We found those happen right at round number points – defined as numbers ending in zero. But it doesn’t have to be that. Even the top 25 would be considered fairly round.”

The research found that people didn’t perceive the gap between university number nine and university number 10 as large. “It was almost negligible, but there was a big difference between the universities on either side of 10. So, if it was 10 versus 11, the tenth was seen as much better, and that is the basic top-10 effect.”

In other words, nine looked good because it was in the top 10, but 11, which might not have been very far from nine on the metrics, was seen as worse because it did not make the top-10 cut.

“The reason we like lists is that they simplify information,” says Isaac. “If I get a list of all the business schools in the world, that is a lot of information to process. A ranked list still has a lot of information, so people tend on their own to mentally create categories. These common categories seem to be around the top 10, 25 or 50. Categorisation is a fundamental psychological process. The university at 10 and the one at nine are spontaneously placed into the same mental categories. We don’t really differentiate between them. But the university ranked 11 is placed in a different category.”

Isaac says the principle applies to anything about which you can make a judgment. “We have been talking about universities but you see rankings all the time – schools, hospitals, places to live, cars, consumer products. It is clear that even across these contexts people are drawn to lists and spend more time on this information than you might expect and it can influence their judgments.”

Lists, finally, make it easier for us to make choices. When we see a list, we know – or believe – someone else has done a lot of research to put it together and saved us the trouble. This third party between us and the things being listed is seen as an expert whose judgment we accept. We trust them, happy to take their word for it, so we can get to the next item on our to-do list.