Like it or not, political and policy success comes down to implementation and the people who actually deliver.

If you are interested in implementation and delivery, nau mai – haere mai, and welcome to He Pōneketanga - an insider-outsider review of the daily and sometimes banal practice between elected and non-elected officials.

When I write this column each month, I will write it from inside a street bureaucrat’s head.

I will lean into the latest public administration research.

I’ll be staying apolitical. But for those who know me, don’t worry; I won’t shy away from the tough stuff.

In today’s column, I’m looking at social investment.

Lots of heat, not much light

Right now, there is a lot of heat about it and little light.

That’s surprising because the Minister for Social Investment (Nicola Willis), also the Minister of Finance, has signalled a reset.

Yesterday, the minister outlined the policy settings for social investment.

It’s exciting.

One aspect I particularly like is its focus on emergent practice.

This focus extends Bill English’s original idea and clarifies whatever the Social Wellbeing Agency was doing for four years.

Emergent practice is important for four reasons.

First, I know some of you think the Pōneketanga is entirely rational and when ministers decide on a strategy, officials go away and implement said strategy, and only that strategy. I hate to tell you, but that’s a myth: it’s a myth whose origin lies in the bedtime stories policy advisers with no delivery experience tell themselves.

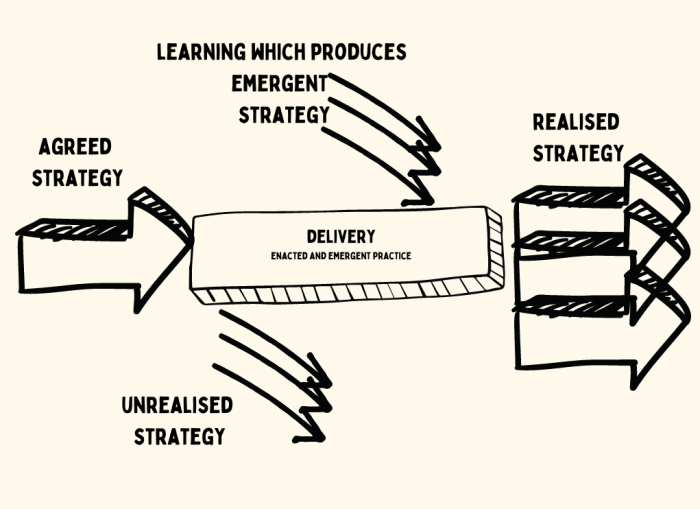

Most delivery and operating models muddle along incrementally, learning how to implement the Government’s strategy. Ultimately, strategy is shaped by and emerges from practice: sometimes the original strategy is realised, and sometimes it isn’t.

If we are honest, most realised strategies combine the original intent and what is learnt through the delivery process.

(Graphic: supplied)

Myth-busting potential

The second reason I am pleased to see social investment focused on emergent practice is it has the potential to cut through the tendency of the Pōneketanga to use its “official” documents as somehow representing reality and innovation.

The “official” documents are constructed to reinforce the assumption that practice in the line agencies or by third-party providers, e.g., Whānau Ora or private health providers, somehow lags behind the Pōneketanga or is not as advanced as the theory.

By emphasising emergent practice, the new approach to social investment not only makes implementation the central focus but might just give us the breakthrough and reduction in compliance costs we have long needed.

Learning from outcomes-based delivery is a much more efficient proposition than controlling an input from afar.

Power to the frontline

The third reason I am excited about the focus on emergent practice is that if you know anything about delivery, you know that most providers (state and non-state) are already managing outcomes in the most interesting, innovative, and unacknowledged ways.

The daily work of frontline workers is a culture of learning and adjusting.

This differs from the theoretical work of constructing data sets, for example, or negotiating to draft a Cabinet paper.

By focusing the social investment function on emergent practice, the Minister for Social Investment has framed the practical work of frontline learning for outcomes as more important than the discursive back-office reasoning and positioning.

About time

This has been a long time coming.

And it is a surprise to me that, other than the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency and myself, others are consciously quiet, which probably tells you a lot.

Those who produce inefficient and ineffective impacts can see the writing on the wall.

If you don’t believe me, look at the original Managing for Outcomes guidance published in the early 2000s, particularly the Pathfinder project. This shift has been two decades in the making.

Bolstering the ‘purple zone’

The final reason I am excited about this approach is that it might also help to strengthen the purple zone, where the “blue” of political activity meets the “red” of public administration.

If you follow my blog and my thinking, you will know I think the purple zone is weak. Not the people; the institutions and the incentives.

The purple zone is weak because emergent and enacted practice is an afterthought.

That is a huge problem in today’s context.

Governance is the most difficult it has ever been.

A focus on emergent and enacted practice is the very thing that can give fresh context to our public policy discourse because it puts delivery theory and implementation at the centre of Cabinet decision-making.

Real-world action

Let me give you an example: instead of having endless debates about business cases, gates, and theoretical discussions about strategy, in a world of emergent and enacted practice, officials and ministers will be having conversations about medium-term investments in particular towns and rural areas in a world of emergent practice.

Those conversations would be about cross-agency service delivery models.

They would be about devolving particular functions and powers to communities and local institutions. Cabinet committees will oversee the learning from pilot programmes so they know where they need to get Parliament to agree to regulatory and rule changes.

They would discuss how to support a particular office in running their “workarounds”, especially where those “circuit breakers” cut through the head-office noise. A public policy advisory and investment system focused on learning from emergent and enacted practice has very different conversations than one having theoretical and conceptual conversations unbundled from implementation, impact and the ethics of both.

Conclusion

I finish where I began.

Almost every conceivable combination of political parties has wanted to see some combination of the following:

- A significant improvement in underlying productivity and economic performance.

- A significant improvement in the position of those who are poorly served by the education, health, employment and justice sectors.

- A healthy, sustainable and productive environment; and higher quality public services while holding tax rates and reducing public borrowing and debt.

These big cross-cutting issues have eluded previous governments.

For the first time in some time, if the Minister for Social Investment can implement the vision for social investment she articulated in her speech yesterday, and sustain the focus on emergent and enacted practice, we might, for the first time in decades, see officials and ministers push through the inertia and gridlock of our policy advisory system and finally let emergent practice lead on outcomes.