It smells of roast chicken, vanilla custard and nondescript cake in the commercial kitchen where busy cooks prepare meals for Canterbury hospital patients, cafes and Meals on Wheels in the region.

In one corner, a cook assembles fresh salads for the cafes.

Across the room, another cook transfers a mountain of potatoes from the boiler to the food processor to make mashed potatoes. Hundreds of meringues sit on trays ready to be assembled for desserts.

Some of the staff have worked there for decades. Their employer might have changed over the years – between 2004 and 2017 it was Compass Group NZ, wholly owned by a British-based multinational, then the district health board took them back in-house – but the work is still the same.

For Canterbury health authorities, taking over food services from Compass in 2017 made a substantial financial difference.

They said it saved them millions of dollars, which brings into question the established practice of using private providers to supply hospital meals.

In 2016, what used to be the Canterbury District Health Board (now Te Whatu Ora Waitaha Canterbury) was under pressure from the government to reduce a ballooning deficit, which it had struggled to bring down since the 2011 Canterbury earthquakes.

Kitchen staff member Fitu Vaegaau handles large quantities of food for meals to be served to patients in Canterbury hospitals and Meals on Wheels. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

Kitchen staff member Fitu Vaegaau handles large quantities of food for meals to be served to patients in Canterbury hospitals and Meals on Wheels. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

When its 13-year catering contract with Compass came up for renewal in June 2017, the board looked at whether it could save money by doing the job in-house.

At the time, Crown-owned organisation NZ Health Partnerships was negotiating a national food services agreement with Compass. It was trying to bring as many district health boards (DHB) as possible to the party to bring the price down.

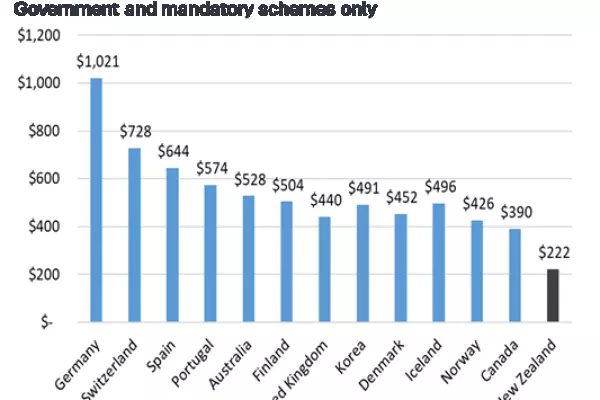

If all 20 DHBs adopted the agreement, it was projected to save between $150 million and $190m over 15 years.

But the Canterbury DHB did the maths and found that switching to in-house catering was a “no-brainer”, said an insider, who asked not to be named.

It wasn't only about saving money, he said. It was also about quality and believing food is an integral part of the clinical process.

The nurses wanted to be involved in shaping meals to best address various patient needs, he said.

In 2018, the NZ Herald reported that patients with allergies had been at "ongoing and significant risk" from Compass Group meals delivered at Auckland hospitals.

One patient suffered an allergic reaction after the wrong meal was delivered and there were 25 near-misses at Starship hospital that year.

Compass Group contracts caused controversy in other parts of the country, with protests outside Dunedin Hospital over meal quality in 2016.

Kitchen staff member Ngaire Holland operates large equipment at the Canterbury food facility. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

In September 2016, the Canterbury DHB announced it would not join the national food services agreement.

The decision was not well received by the government, the insider said. Not having the second-largest DHB in the country joining the agreement would bring prices up for everyone else. Auckland, Counties Manukau, Waitematā, Southern, Nelson-Marlborough and Tairawhiti DHBs joined the agreement.

Because several DHBs declined to come on board, the estimated savings fell to between $30 and $40m over the 15 years, RNZ reported at the time.

The Canterbury DHB already owned the kitchen facilities that Compass had been using, making the move easier than it would be in other districts where there was no onsite kitchen.

It took on all but a couple of the 300-odd Compass food staff at the time of the switch in June 2017.

Food services would continue as usual – without the profit margins. This included delivering each year more than one million patient meals to several hospitals, 120,000 Meals on Wheels meals and food for several hospital cafes.

A Canterbury DHB press release in 2017 said the current menus, which already had “high levels of customer satisfaction”, would be enhanced over time.

Six years later, it appears the move has been a success. Waitaha Canterbury said in a statement millions of dollars have been saved and food quality had improved.

Waitaha Canterbury general manager commercial services Rachel Cadle declined to give the exact amount saved, citing commercial sensitivity, but said “managing the service ourselves instead of contracting it out has allowed us to save millions of dollars”.

Other Te Whatu Ora districts do catering in-house, including Hawke’s Bay, Waikato, Hutt Valley and West Coast.

BusinessDesk asked Te Whatu Ora to supply details on how these food services were run earlier this month, but the request was turned into an Official Information Request, which takes up to 20 working days to process.

A cook wraps a salad that will be served to a patient with specific dietary requirements. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

E Tū union health sector organising director Sam Jones said food workers kept the same terms and conditions on their contracts after the switch.

Being directly employed by the DHB meant they could access a few extra benefits, such as income protection during the pandemic, which contractors did not necessarily get to the same degree.

Staffing and food costs for the DHB would have been the same or higher than they were for Compass. So how did Canterbury save money?

“We only pay cost price for things like ingredients and staff wages,” Cadle said.

“We do not have fixed contract overheads to pay. In other words, if a sandwich costs $1 to make for a patient meal, that’s all we pay, as we don’t have a profit margin element on top.

“We also run our cafes now, which we receive some retail revenue from."

Jones said he did not have enough information to know where and how Compass added value, but the company had been “pretty good to deal with us as a union”.

“We do not believe as a union there should be profit in the health system,” Jones said. At the same time, if a private business invested in a brand-new kitchen outside of a hospital where the public purse could not afford it, or if it was able to negotiate food prices down, it could bring benefits, he said.

Trays of meringues are ready to be assembled. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

In a statement to BusinessDesk, Compass Group NZ said it was confident it was providing quality food to hospitals across the country, with patient satisfaction ratings consistently exceeding 90% across its network of 12 health districts.

Customers chose outsourcing so they could focus on their core service, Compass said.

Outsourcing provided consistency, quality and flexibility. Customers did not want to deal with staffing challenges or invest in food service infrastructure, equipment and ongoing maintenance, the statement said.

Otago University's centre for health systems director, Robin Gauld, said the move from having 20 DHBs making decisions about hospital suppliers to Te Whatu Ora making centralised decisions after the health reforms would lead to “robust discussions” in the sector.

Some would say commercial suppliers are more efficient, while others might say it should be a public investment, he said. But, in the end, what matters is how well the service is run.

Most airlines contract out their catering because it's not part of their core business.

Food could arguably be seen as a core part of healthcare provision because it has an impact on patients' wellbeing and recovery, Gauld said.

“My suspicion is [Te Whatu Ora] will say, ‘We have enough going on, let's contract everything out.'”

Te Whatu Ora would now be in a "monopsony position" – a market situation in which there is only one buyer – like Pharmac.

“Often, as members of the public, we see companies such as Compass as being in the driving seat," Gauld said.

"But actually, Te Whatu Ora are in a much stronger position than DHBs ever were to negotiate with firms like Compass.

"It was also a 'massive opportunity' for Compass, which could potentially get the contract for all hospitals around the country."

Te Whatu Ora did not answer questions by deadline.