Yesterday, part 1 looked at the acrimonious relationship between GPs and the government when it comes to funding. Part 2 looks at how much money GPs actually make.

In 1977, Dr Kantilal Patel opened a small general practice in Ōtara with his wife Ranjna. The business has since grown into one of the largest networks of GP clinics in Aotearoa.

Tāmaki Health has ownership of 49 practices and urgent care clinics from Whangārei to Christchurch, serving about 299,000 enrolled patients.

More than half of Tāmaki’s clinics are very low-cost access practices serving very high-needs populations.

Last year, Australian group Mercury Capital purchased most of the business’ shares. But the couple’s son, Rakesh Patel, says the family never saw the network as a corporation.

“We felt that if there was a patient in need and we were able to serve them, the business would just take care of itself.

“At the end of the year, we ask the accountants how we are going.”  Rakesh Patel says his family never saw Tāmaki Health as a corporation. (Image: Supplied)Patel, who remains on the company’s board after starting in operations in 2000 and taking on various roles in the business over the years, says the business grew in response to the need in South and West Auckland and has recently expanded to Christchurch.

Rakesh Patel says his family never saw Tāmaki Health as a corporation. (Image: Supplied)Patel, who remains on the company’s board after starting in operations in 2000 and taking on various roles in the business over the years, says the business grew in response to the need in South and West Auckland and has recently expanded to Christchurch.

Building a healthcare network does not happen overnight. Tāmaki was built on patients’ and clinicians’ trust, he says.

From day one, before it became the government's policy, Kantilal Patel decided his practice would never charge a child under 18. Several Tāmaki Health clinics have never made money, but being part of a larger group takes the pressure off, Patel says. After-hour clinics in the network also help balance the load.

“No healthcare professional or even manager chooses a career in this industry based on profit. The way that the system works is profit is a result of efficiency, the types of services you provide and how you manage your operations.”

Commercial interests

At the heart of the conflict between GPs and the government on funding is the fact that GPs make a profit and there is little transparency on what they make.

Former health minister Andrew Little told BusinessDesk in November he did not like the idea of people's ill health being the source of profit to others.

There is a tension here because such profit-makers form a huge part of the health system, and “that won’t change in a hurry”, he said then.

In December, Little wrote a terse letter to GenPro in response to its ‘Save Your Family Doctor Service' campaign, accusing them of making inaccurate claims “in furtherance of commercial interests”.

“Part of being an honest broker with you is making it unambiguous that anyone receiving taxpayer funding needs to expect a high degree of scrutiny, firstly about the facts of that funding, and secondly to provide public assurance that taxpayers are getting value for their investments."

He told BusinessDesk in January (before it was announced that Dr Ayesha Verrall would replace him) that the issue of capitation funding needs to be addressed, “but this is not just a funding issue and unquestioningly following the same primary care model”.

Theoretical deficit

So, how well are GPs actually doing out of health? If you believe GenPro’s campaign, they are on the brink of collapse.

The Sapere report, completed in July 2022 after it was commissioned by the government as part of the health reforms, supports the claims.

It estimated total general practice revenue at $1.672 billion, excluding ACC funding. Total practice costs came to $1.809b, including $1.354b in salaries and $455 million in overheads in this theoretical estimation.

Sapere calculated GP practices collectively run a theoretical net deficit of $137m per annum – a 7.6% loss (spread across all GP practices), at current levels of funding and costs. Practices serving a high-need population were doing “considerably worse”.

But this was a theoretical calculation, and the reality is more nuanced.

GPs are unlikely to be recording such financial losses thanks to unpaid work, below-market salaries, above-inflation fee rises, reduced and delayed access and shorter appointments for patients, the report said.

Corporate results

Most GP practices keep their financial results private, making it impossible to gain a clear understanding of their financial reality. But a rise in corporate ownership in recent years is starting to make GPs’ bottom line more visible.

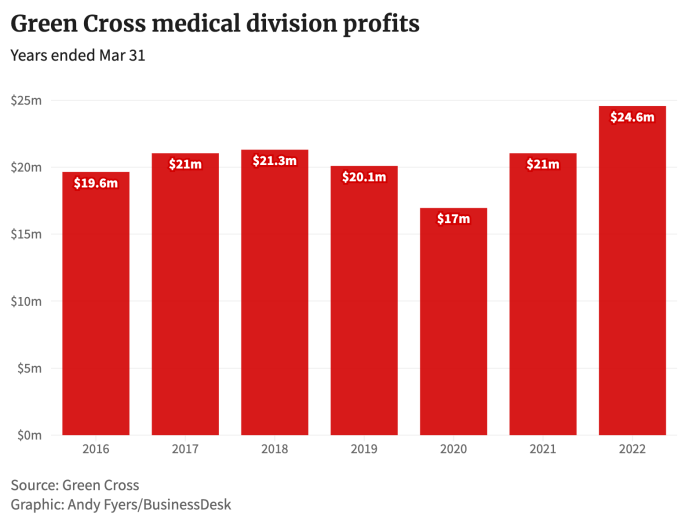

Green Cross Health has ownership in 58 general practices serving 358,000 patients across the motu. It also owns pharmacies and provides community care.

It employs about 1,200 people in its medical division, including 408 doctors.

As the company grew its network from 31 medical centres in 2016 to 58 in 2022, so too did its revenue and profits. Its medical operating profit almost tripled from $4.4m in 2019 to $16m in 2022. Its medical operating revenue was $110.9m in 2022.

As the company grew its network from 31 medical centres in 2016 to 58 in 2022, so too did its revenue and profits. Its medical operating profit almost tripled from $4.4m in 2019 to $16m in 2022. Its medical operating revenue was $110.9m in 2022.

“Practices need to individually run profitably to be able to provide best practice health care to their enrolled patients and to support re-investment in innovation and improved service delivery,” says Green Cross Health medical general manager Wayne Woolrich.

Third Age Health is another publicly listed company that owns general practices. The group’s core business (providing primary care in aged care facilities) enrolled 3,400 new patients in the first six months ended September, a 6.7% increase from the prior half-year, which drove revenue growth up 16.7% to $2.8m.

Third Age Health’s general medical practices enrolled 3,425 patients, a 14.2% increase, and brought in $1.8m in revenue.

Despite this growth, the group’s net profit dropped 51.8% in the six months to September to just $324,000.

The company said the lower profit was due to investing in a platform for growth, integration and acquisition costs, and an increase in the amount of non-cash amortisation.

Return on investment  Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell says not everyone in general practice is struggling for money. (Image: NZ Herald)

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell says not everyone in general practice is struggling for money. (Image: NZ Herald)

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell shares Little's personal dislike of health profits.

Commenting on the recent rise in corporate ownership of general practices, he says: "It is interesting, isn't it, that on the one hand, you hear that nobody can make any money in healthcare; on the other hand, you see that people are prepared to invest in healthcare businesses. Both of those things probably can’t be true."

Not everyone in the primary care sector is struggling for money; some people are doing very well, he says. Te Whatu Ora needs to gain more clarity on the financial disparities in the sector as part of reviewing the funding model.

Profit is a dirty word in health, and it shouldn’t be, says GenPro chief executive Philip Grant.

“One of the principles of having a private business is that you are expecting a return on investment.

“It is absolutely right that individuals who have invested resources while mortgaging their family home should return a profit.”