Read part 2 tomorrow: 'A dirty word': GP profits

The waiting room is deceptively quiet. A few people are waiting to see a doctor on a Monday morning at Totara Health’s Flaxmere practice. Before the pandemic, the room would have been full. This does not mean fewer people are sick, or that they can get an appointment quickly. An increase in need, along with Covid-19 measures, has forced the clinic to triage patients on the phone and move 40% of appointments to teleconsultations.

There are no gaps anywhere for the 65 staff - including 16 doctors, 11 practice nurses, counsellors, health coaches, pharmacist facilitators and admin staff - working across Totara’s two surgeries in Flaxmere and Hastings. Every day is full, with more than 650 patients going through both practices each day - and many more in winter months. A few years ago, patients needing an appointment would have been seen within a couple of days. Now they wait up to two weeks for non-urgent appointments.

“It’s a bit like the water temperature going up a little bit at a time and you don't notice it until you are burning. And of course Covid has exacerbated the problem,” Totara Health manager Howard Dickson says.

Tōtara Health shareholders Dr Rachel Monk, Dr Sandra Jessop, Howard Dickson and Dr Bryce Kihirini run two busy clinics in Flaxmere and Hastings. (Image: Supplied)

GPs' revenue

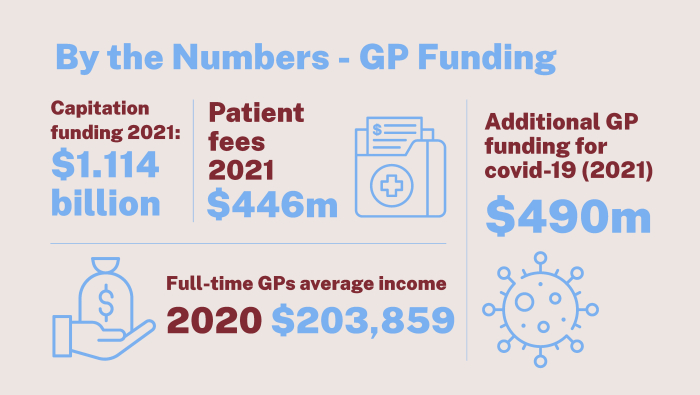

Totara Health clinics are among about 1000 general practices across the motu, looking after more than 4.5 million enrolled patients and receiving more than $1 billion in public funding each year - about 5% of the total operating health funding. On top of that, GPs charge patients fees, the total of which was estimated at $446m in 2021 by a recent report, done by Sapere on behalf of the government. GPs working full time earned an average personal before-tax income of $203,859 in 2020, with 38 per cent earning more than $200,000 a year, according to a College of GPs workforce survey.

In 2021-22, the government paid general practices, pharmacies and other primary care providers $490m extra to provide Covid-19 testing, vaccination and care in the community. The Covid funding, which GP owners have described as generous, helped many stay afloat over the last three years. But it has now been drastically reduced, leaving a burnt out and short-staffed workforce in its wake, and no long term solution for the rising costs of running a general practice, the unmet need in the community and staff shortages.

‘Woefully inadequate’ funding

When Dickson, his GP wife Sandra Jessop and Dr Stuart Foote, who has since retired, bought the Hasting and Flaxmere surgeries in 2003, they had 4000 enrolled patients. Almost 20 years later, Totara Health’s roll has quadrupled to 16,000 patients. Staffing has grown to match the patient increase - the practices have maintained the same ratio of doctors per 1000 patients since 2003. Two new doctors have become directors and shareholders of the practice, with more to join soon. The owners have tried to slow the growth over the last five years, but cannot turn patients away in Flaxmere, where Totara is the only surgery. Jessop has worked in the Flaxmere community for 34 years.

Totara was formed shortly after the government introduced a capitation formula to fund general practice following health reforms in 2001. The formula, which is still used today, gives a set amount for each enrolled patient at a practice, based on age and sex. Capitation funding covers about 2.5 visits per patient a year on average, but high-needs patients can visit a lot more, Dickson says. At Totara, some patients come 20, 30, 40 times a year, making the formula “woefully inadequate”.

Between 2006 and 2009, Very Low Cost Access (VLCA) funding was introduced for practices serving at least 50% high needs patients (Māori or Pacific ethnicity, or living in an area scoring high on the NZ deprivation index). VLCA practices receive extra funding in exchange for capping the fees they charge patients (currently at $19.50). Totara Health qualified to be VLCA, with 70% of its patients being low income Māori and Pasifika. The owners did the maths and thought they would be no worse off by going VLCA, and they knew their patients needed the low fees.

Howard Dickson started Totara Health in 2003 with his wife Dr Sandra Jessop. (Image: Supplied)

But already at the time, the funding did not take into account the complexity of the patients’ health needs, which have become greater in the last 20 years with overloaded hospitals sending more patients back to their GPs, Dickson says. Costs have risen dramatically over the same period, with a global GP shortage compounding the issues. Totara Health is short of 3 doctors, which it has tried to recruit for three years, incurring great costs. Meanwhile the funding formula has remained the same.

“Our community needs our support and we have provided it.

“But the government has complete control over our funding and they have been steadily strangling us as a business. They are doing this in an environment where hospitals are hopelessly under pressure and unable to cope,” Dickson says.

Covid funding a lifeline

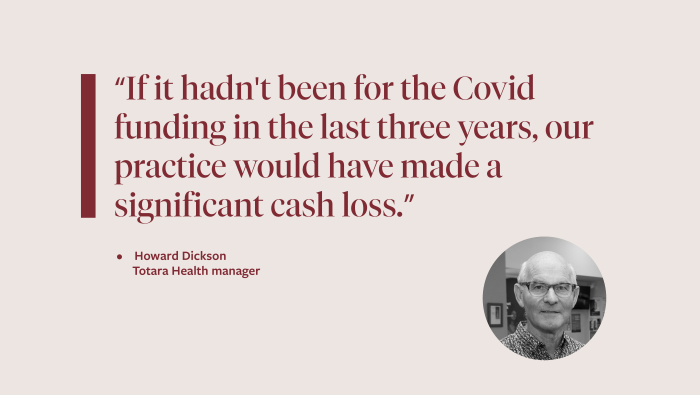

Despite the challenges, Totara Health appears to be treating its patients and staff generously, and continues to turn a profit (although Dickson would not disclose amounts). It is down to the scale of the business, doctors working longer hours, consultation times getting squeezed and the temporary Covid-19 funding, he says.

Five years ago, Totara decided to make doctors and nurses’ consults free for women 30 and under - the most vulnerable group in its community. In the last 12 months, it also offered its nurses pay parity with hospital nurses, before primary care nurses went on strike in October to ask for pay parity with hospital nurses, who earn about 10% more.

“If it hadn't been for the Covid funding in the last three years, our practice would have made a significant cash loss,” Dickson says.

With the reduced Covid funding, Totara Health is set to lose money next year.

“Our practice is going to have to find ways to provide less service. Because we are not funded for what we are currently providing."

Dickson is not the only one to struggle.

Save your family doctor

In November, GP owners' association GenPro launched a campaign to ‘Save Your Family Doctor’. GP clinics are under threat due to workforce issues, increased workloads and underfunding, the campaign says. This is putting avoidable pressure on the rest of the health system and directly impacting the health of patients, who are waiting longer to see their GP, if they can enrol with a practice at all.

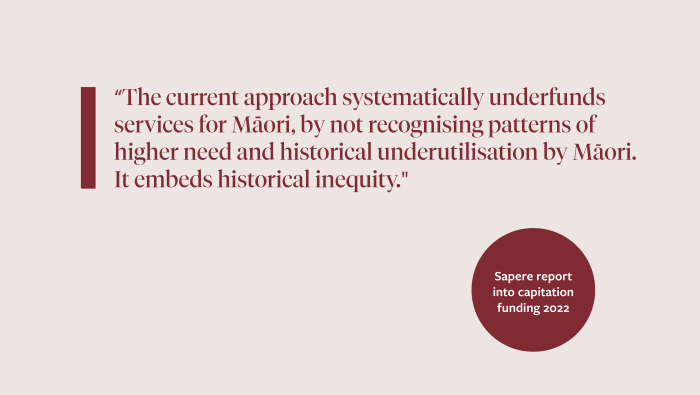

The government has promised for years to review the capitation funding formula which originated in 2003. In early 2022, it commissioned the Sapere Research Group to look at the formula with a focus on equity issues in terms of access, as part of the health reforms. The review was completed in July but kept under wraps until it was quietly released on November 16. The conclusions were damning. Very high-need general practices, such as Totara Health, would need a funding increase between 34% and 231% to deliver an appropriate level of service to their patients.

One of the main issues identified in the report is that capitation funding does not account for ethnicity, morbidity and deprivation. As a result, general practice revenue “lies below the likely true cost of delivering care at current levels”, the report found.

It modelled the funding increases needed “deliver higher than historic levels of care to priority populations, to represent a new normal”.

“The current approach systematically underfunds services for Māori, by not recognising patterns of higher need and historical underutilisation by Māori. It embeds historical inequity." the report said.

For most practices, the median modelled increase was between 10% and 20% of current capitation revenue. Overall, government funding would need to increase by more than $600m each year for clinics to be able to properly address the unmet need in the community, particularly for Māori and Pasifika patients.

Te Whatu Ora has distanced itself from the Sapere review. Primary care group manager Adeline Cumings says it will be “an important input for further advice on possible changes to funding settings”.

“A key takeaway from the review is that Māori, Pacific and deprived populations are poorly served by the current capitation formula, resulting in a worsening of health inequities. Budget 22 includes $86 million over four years to more equitably allocate primary care funding to general practices for high needs population,” Cumings says.

This is a drop in the ocean compared to the $614m per year the review said was needed to address 70% of current unmet need.

‘It is really urgent’

The government’s lack of urgency around GP funding is causing dismay and anger in the sector. Several GPs and sector leaders told BusinessDesk they feel completely let down.

“My views on that are unprintable. I am astonished that this isn't a priority to get it sorted out. It isn't sustainable,” Dickson says.

College of GPs’ Māori special representative group chair Rachel Mackie would like to see more urgency from officials in addressing the primary care crisis.

“A lot of our Māori patients will suffer because they are not as assertive in getting what they need. They will sit back and wait and that is a real worry. That means poorer outcomes for them. It is really urgent.”

A funding boost is sorely needed, but pouring more money into a system that doesn’t work for Māori won’t be enough to improve health outcomes, Mackie says

“You can't put everyone in the same boat and expect the same outcomes.”

College of GPs’ Māori special representative group chair Rachel Mackie says addressing funding is urgent, but pouring more money without fixing an inequitable system won't fix the issues. (Image: Supplied)

Only 4% of this country’s GPs are Māori, and this needs to increase, she says. High needs patients need access to wrap around services at their GP, including cultural, social and whānau support.

“When I started working as a GP at a high needs practice, I would spend way too much of my consultation time on social issues. I don't mind doing that but it is probably not the best use of my time.

“We ended up getting someone to help with that aspect and that took the load off to focus on the health issues. Instead of thinking of surviving, [the patients] can then think about improving diabetes and other chronic conditions.”

Māori-owned or governed clinics already have this holistic approach, with great results, Mackie says. But piecemeal funding trying to solve massive, historic underinvestment in Māori services, makes it hard for these organisations to succeed in the long term. Juggling funding applications and multiple contracts end up taking time away that could be spent with patients.

Pay parity

It’s not just GPs that are struggling. Primary care nurses have been given increasing responsibilities in general practice in the last decade to support a dwindling GP workforce and overwhelmed hospitals. Pay increases have not followed, leaving them earning about 10 per cent less than their hospital counterparts.

Tracey Morgan is one of 4200 primary care nurses who went on strike in October to demand pay parity. The NZ Nurses’ Organisation (NZNO) representative is a practice nurse manager at a Rotorua medical centre. Interestingly, the nurses are asking the government for a pay increase, not their direct employers, the general practices. They want ring-fenced funding for their wages, with annual increases matching inflation, to be included in capitation funding.

“Our general practices would love to pay nurses more. But their annual increase [in capitation funding - this year the increase was about 3%] is not enough. it gets squashed up,” Morgan says.

“They just can't pay us and it's unfair. They can't match what Te Whatu Ora pays.”

Practice nurse manager Tracey Morgan says GP nurses are overworked and underpaid. (Image: Supplied)

The government keeps giving practice nurses new jobs to do (screening, swabbing, immunisations, following up) but staffing increases do not match the demands, Morgan says. Covid has added an enormous workload, stretching practice nurses to their limits. In October, Morgan saw 37 patients in one day because two nurses were away sick and she had no backup.

“I almost wanted to burst into tears. I shouldn't have to see 37 patients on my own as a nurse when a doctor sees 25 patients max. It is so surreal when you think about what we have to do as nurses, and the fatality risk if we don’t address this.”

Following the strikes, former health minister Andrew Little announced in November a $200 million-a-year fund to bring up to 20,000 community-based nurses and healthcare workers’ pay into line with public hospitals. Nurses working in aged-care facilities, hospices, homecare support and Māori and Pacific healthcare organisations would be targeted first for the pay increase. GP nurses were left out.

Despite angry protestations from the sector, Little told BusinessDesk - before it was announced that Dr Ayesha Verrall would replace him - that GPs run private businesses and it is up to them to increase their nurses’ pay. He also pointed to $106m extra funding given to GPs over the last two years “to support cost pressure increases”, which should have been used to give nurses a pay rise.

GenPro chief executive Philip Grant says the figure is misleading because it includes more than $12m in anticipated patient fees increase and more than $40m for free or low-cost patient appointments. When pressed on the issue, Little says there is no evidence of the pay gap anyway, dismissing information provided by NZNO and GenPro as "unreliable".

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell's view on pay parity is more nuanced. He does not deny the existence of a pay gap, but does not accept the onus is fully on the government to close it.

"From our point of view to have the kind of health system we want to have we do need people in the funded sector paid on comparable rates to those in the hospital. No argument from us about that. How we get there, whose responsibility it is to achieve that between us and the private providers, that is a more complex question."

So, what exactly is the evidence? The national collective agreement for primary care nurses shows a clear gap on its pay scales, compared to hospital nurses’ pay scales.

The gap will rise from 10.7 % ( or $8000) to about 20% ($20,000) in March, following an Employment Relations Authority ruling late last year on interim pay equity rates. An experienced public hospital nurse’s base salary will rise to $95,340 as a result of the ruling - $20,000 more than the top pay rate in the primary care nurses’ latest collective agreement. Based on this, GenPro calculated that an extra $32.34 m in capitation funding a year would be needed to close the gap.

But the collective agreements only dictates a minimum salary; employers can, and many do, pay more than that. Because GPs’ books are private for the most part, it is difficult to know how much every single GP nurse is getting paid. NZNO and GenPro surveyed some of their members to paint a clearer picture, but what they have collected was deemed unreliable data by officials.

“It feels like the [former] minister's statement about lack of evidence might mean he has seen no evidence to support the answer he would like, rather than the actual workforce and service crisis which is playing out across the country, GenPro chief executive Philip Grant says.

"The longer this crisis continues, the more that general practice employers are being forced to offer increased terms just to be able to compete in the recruitment and retention of essential nurses, and to be able to afford to increase those terms, they are having to cut services or opening hours elsewhere".

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell says he wants GP nurses to be paid fairly. (Image: NZ Herald)

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell says he wants GP nurses to be paid fairly. (Image: NZ Herald)

NZNO chief executive Paul Goulter also disagrees with the minister. The union’s survey results showed significant gaps, he said.

“The problem hasn't gone away at all and just denying the evidence is not going to fix it.”

He said the government should be doing the work to find out what is happening on the ground, rather than ask unions and GP associations, who have considerably less resources, to do the work and then criticise the methodology they used. Still, the union is working on collecting further evidence through a wider survey of its members, Goulter says.

He will not rule out more striking on the issue, but would rather work with the new minister and GPs on closing the gap.

Longstanding standoff

To understand why the relationship between GPs and the government has become so acrimonious, Victoria University public policy senior lecturer Verna Smith says we need to go back to the birth of this country’s health system.

New Zealand established the very first National Health Service in the world in 1938. The UK followed a decade later, with a critical difference.

Here, the government legislated for GPs to provide healthcare for free, but the doctors fought a big campaign to be allowed to charge fees, Smith says. In the UK, the same thing happened but the Government won and primary care remains free of charge to this day. By contrast here, patients pay up to $70 for a GP consult, on top of the Government and ACC funding GPs get.

As a result, the government has a sense that GPs should really meet the costs of delivering the service and invest in the community. No meaningful partnership was formed where GPs could negotiate their funding, and a longstanding standoff started.

“Relations took a turn for the worse after owners wanted to charge more and wanted more funding from the state.”

Academic Verna Smith says GPs need a better way to advocate for themselves with the government. (Image: Supplied)

Academic Verna Smith says GPs need a better way to advocate for themselves with the government. (Image: Supplied)

If the government had formed a closer partnership with GPs, the system would be more efficient, she says.

In the UK, GPs are private providers, contracted to deliver their services according to the rate set and negotiated between their union and the Government. They have for many years negotiated and debated the right amount for their services, including money to purchase and maintain surgeries, IT and staffing costs. UK’s GPs are some of the best paid in the world, Smith says. They are not unhappy about the arrangement because they have a lot of power to negotiate funding with the government.

Smith is hopeful that with the health reforms centralising 20 district health boards into a single entity responsible for funding - Te Whatu Ora - the relationship with GPs will start to heal. Te Whatu Ora needs to sit down with GPs and start talking seriously about how to make primary care more accessible, Smith says.

“It's in everybody's interest to solve this standoff.”

Campbell says the strains in the relationship between GPs and the government are a result of real pressures, long term underfunding and the changing nature of the health sector. Reaching an agreement with the sector on a more equitable capitation formula is a matter of high priority, he says. Extensive consultation with the sector is needed, which will require a certain degree of trust. The centralisation of decision-making should make it easier, he says.

"The pressure is on us to reach a new arrangement, but it won't happen overnight. We would like to get it resolved sooner rather than later but there are multiple parties involved and so it is not entirely up to us."

This article has been amended to reflect the $490m in funding went beyond general practices.