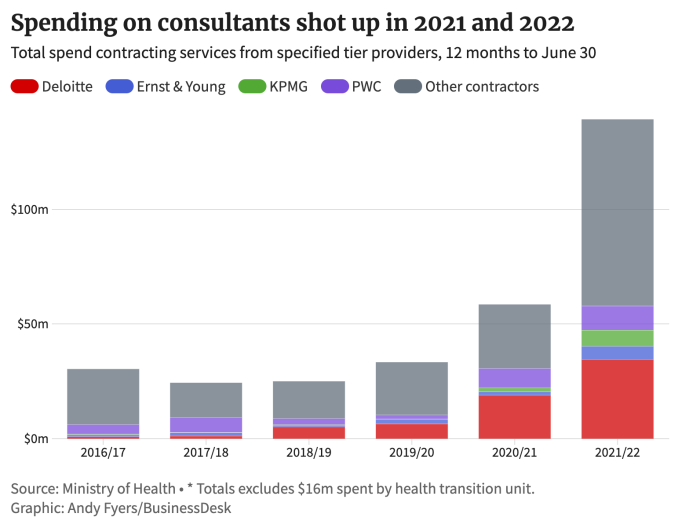

The Ministry of Health has spent nearly $200 million on consultants in the two years to July 2022, almost twice as much as it did in the four years prior. On top of that, the transition unit that oversaw the health reforms spent $16m on consultancy firms.

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell said the board would crack down on the spend.

“There has been a hollowing out of expertise in a number of areas in the health system in favour of consultancy companies,” he said.

Hiring consultants was sometimes necessary, but the system needed its own internal expertise.

“The more you hire consultants, the more the workforce gets weakened. Indeed, we have got people who are very good at their job being poached by consultancy companies so they can sell their services back to us.

“If we can't cut the overall spend on external consultants, we won't succeed in our aims. It's as simple as that.”

Sharp increase

Over the past six years, the health ministry spent $321m on consultants, according to data obtained under the Official Information Act.

The spending rose sharply in 2020-22, a busy period for the ministry between a global pandemic and a major health reform. It went from $33.3m in 2019-20 to $58.5m the following year and $139.2m in 2021-22.

A Ministry of Health spokeswoman said the increase was largely to boost its covid-19 response. For example, the last financial year included the set-up and administration of the covid vaccine and immunisation programme, she said.

For context, the government also increased funding to frontline services in the past two years, with almost $3.8 billion incurred in 2021-22 for the national response to covid across the health sector, including funding for general practices, pharmacies and hospital services.

The health reforms, announced in April 2021, replaced 20 district health boards with Te Whatu Ora and the Māori Health Authority. The Health and Disability Review Transition Unit (HTU) was set up in August 2020 within the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC). It ran until September 2022 at a total cost of $30m.

The health reforms, announced in April 2021, replaced 20 district health boards with Te Whatu Ora and the Māori Health Authority. The Health and Disability Review Transition Unit (HTU) was set up in August 2020 within the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC). It ran until September 2022 at a total cost of $30m.

Ernst & Young’s (EY) Stephen McKernan, who was previously director-general of health, led the unit, which was staffed with public servants, secondments, fixed-term employees, contractors and consultants.

It started with a small number of staff in 2020 and grew to 135 staff at its peak, according to department executive director Clare Ward. By the end of May 2022, the headcount of the unit was 38.

Value for money?

EY received $11.9m out of the $16m the HTU spent on external consultants. The expenses covered 24 EY contractors, including McKernan, who worked in the unit during its three-year existence. Not all of them were full-time. The HTU delivered “high-quality results”, earning strong ministerial satisfaction, Ward said.

But Te Whatu Ora's Campbell said the board had been surprised at how limited the preparations for the changes it was now driving were.

“Getting accurate information on what is going on in the system is still a huge problem and we would have thought more would have been done before our establishment,” he said.

Health commentator Ian Powell said he did not believe the HTU had been good value for money. “Relying on business consultants for health decisions is rather like asking Wayne Brown for advice on etiquette.”

National's health spokesman, Dr Shane Reti, said the unit did “a terrible job”, wasting an unbelievable amount of money without delivering key aspects of the reform, such as how the new health system would be funded. He believed the unit was wound up earlier than planned despite about $10m extra originally budgeted for the reforms for the 2022-23 year.

A job well done

DPMC’s 2021-22 annual report said expenditure on the HTU was lower than the original budget due to the earlier than expected transition of functions and activities to the two new health agencies.

DPMC communications director Catherine Delore said the unit was not disestablished early, nor did it fail to deliver on what was required.

It did highly complex, detailed policy and design work, which was completed within demanding timeframes, she said.

“As a former director general of health, and chief executive of two district health boards, Stephen McKernan was able to bring all the required skills and experience to the role, and to quickly build a team of people around him that he could work with at pace to deliver high-quality results.”

Some of the outstanding funding was returned to the crown and the remainder transferred to the new health entities, Delore said. Te Whatu Ora chief executive Margie Apa said it continued to work with EY to support ongoing work related to the reforms.

'Taxpayer-funded rort'

A ministry spokeswoman said it hired large consulting firms, including the 'big four', because of “the breadth of specialist service that they are able to offer”, especially where projects have a short delivery time frame.

“These large consulting firms have access to global resources which are often not available in NZ and in particular at short notice.”

Experienced healthcare investor Michael Haskell said the amount of money spent on external consultants rather than on frontline staff was a “major problem”.

“Bureaucrats and external consultants tend to protect one another in a taxpayer-funded rort that goes a bit like this: the bureaucrat hires a high-priced team of consultants from PwC/Deloitte/KPMG/EY and pays them hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars and then the external consultant produces a report stating that the healthcare sector needs more funding for more bureaucrats, and then the cycle repeats itself.

“Note that it's our doctors and nurses leaving for Australia and not our bureaucrats or consultants, because they know they have it pretty cushy here.

“Until this cycle stops, it will be very difficult to improve our healthcare sector to any material degree.”

The big four

Over the past six years, the health ministry forked out more than $71m in contracts with Deloitte. About half of the work the consultancy firm did was in 2021-22, when it received more than $34m in contracts.

Senior communications manager Anna Radich said Deloitte did not comment on client agreements. “Clients typically engage us for critical skills, service capabilities, innovation and solutions that they need advice and support to implement,” she said.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) was another major contractor with the ministry, scoring about $36m in contracts between 2016 and 2022.

PwC’s Hauora co-lead and partner Tamati Shepherd-Wipiiti said the health team represented a small proportion of the firm’s overall consulting services. It had more than 30 full-time staff, half of whom had a clinical background.

Clients included aged-care providers, government health agencies, Māori and Pacific health organisations, Primary Health Organisations, public and private hospitals.

“We are often asked to come in and resolve an important issue, add additional capability to teams and help reset strategies," Shepherd-Wipiiti said.

"An example of this was tackling low Māori vaccination rates, which saw the Hauora team work alongside providers to significantly lift Māori vaccination rates.”

Over the past six years, EY received more than $13m for health ministry contracts (on top of the $12m for its work on the HTU). The firm did not answer questions by deadline.

KPMG scored $10.4m in contracts with the ministry between 2016 and 2022, including $7m in 2020-21.

Head of marketing and communications Fiona Woolley said KPMG had a health practice that supports organisations across the sector as they navigate the changes in the system.