Just 18 months ago, Professor Greg O’Grady, an Auckland surgeon, was wielding a scalpel. Now he’s at the cutting edge of commerce, having traded the operating theatre for the office as chief executive of medtech startup Alimetry.

O’Grady is one of a growing number of entrepreneurial clinicians who are joining intellectual forces with their colleagues in engineering, fuelling a boom in medtech businesses garnering global interest.

Alimetry, the company he co-founded with bioengineer Armen Gharibans, is on the verge of international success after earning United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval to market a device that is effectively an electrocardiogram (ECG) for the gut rather than the heart, measuring electrical signals that allow often hard-to-diagnose conditions to be identified and treated, without invasive tests.

Electrical activity

“The heart is driven by electrical activity and so is the gut and you pick up that electrical activity on the body’s surface with the sensors. It’s difficult because the signals are 100 times weaker than the heart so we need a big patch of electrodes to pull that out,” O'Grady says.

He says in the past, some patients, for example, those with chronic nausea, have endured an average of 3.5 tests for five years to reach a diagnosis.

O’Grady’s dream is to see the Alimetry device used in every hospital in the world. The FDA approval and CE mark it gained last year have opened the door to the lucrative American and European markets.

The device is already used in New Zealand hospitals, both clinically and in trials. He’s had no qualms about leaving his surgical career behind.

“When you’re a surgeon, you can treat only one patient at a time. When you do this, you have the potential to have a vast impact on the whole gastroenterology field and that’s much more inspiring and something I’m very happy doing.”

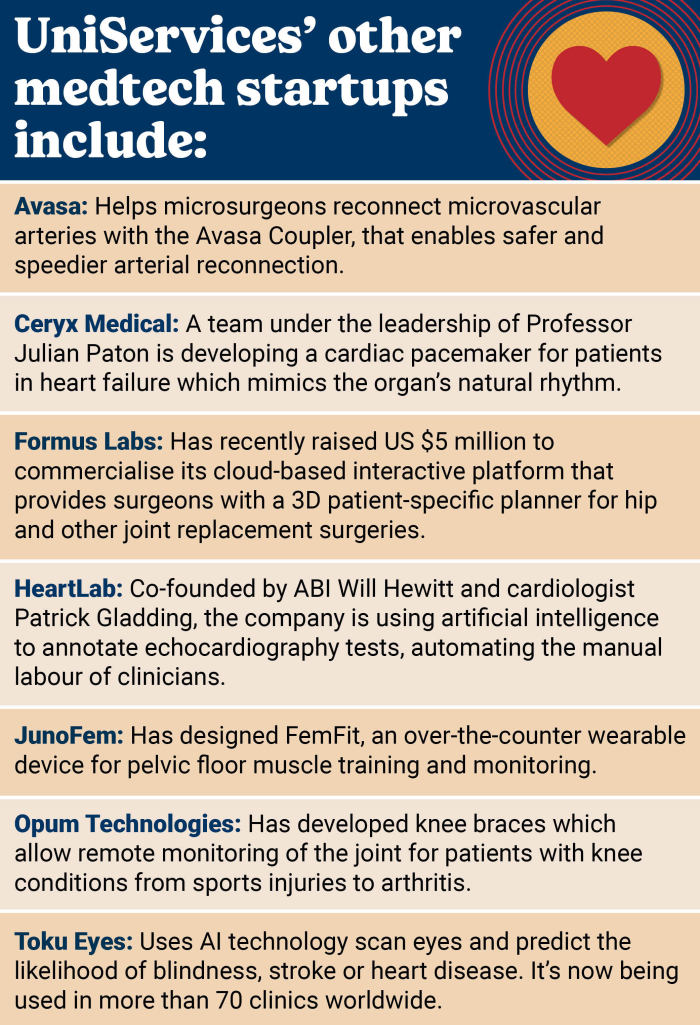

Alimetry – launched in 2019 – is one of a burgeoning number of medtech startups that Auckland University’s UniServices has helped launch since 2016 with the aim of bringing innovative technology conceived mainly in its Auckland Bioengineering Institute, but also elsewhere in the university, to the global market.

The university's Auckland Bioengineering Institute's (ABI) not-so-secret weapon is the teamwork it fosters between engineering and clinical brains.

“The challenge with medtech is that engineers come up with beautiful solutions that doctors don’t care about and the problem with doctors is they come up with really bad solutions for things that bother them every day,” says UniServices' executive director of commercialisation, Will Charles.

“If you can get those things working together in the same research institute, you start from the point of view of this matters, and this is the best way of designing something so you get closer to a real clinical need through engineering rather than working in silos.”

O’Grady says that’s a crucial gap that he’s tried to bridge with both Alimetry and an earlier company he co-founded in 2017, The Insides Company, which devised a device to reinfuse patients whose gut contents – chyme – have to be diverted away after colorectal surgery or to allow the wounds to heal.

“As surgeons, we’ll innovate by finding something on the shelf and adapting it to the problem rather than designing a solution from the ground up. Engineers bring a first-principles approach to solve problems that clinicians lack.”

Tailored vaccines

Meanwhile, Charles says the potential for medical technology is practically infinite because of unmet clinical needs and a move from population to individual-based care with precision medicine.

“In future, not far away, you will be able to get an individual vaccine tailored to your RNA,” Charles says.

He’s overseen the birth of 59 companies through UniServices since 2016, of which 21 (36%) have been medtechs. Fifteen of the 59 – four of them medtechs – have since closed.

Chief executive Dr Andy Shenk says UniServices is now operating to a different model than it did in the past after establishing an inventors’ fund in 2016.

“Before this, we did what many universities around the world did, which was to package up the intellectual property from research, license it to a start-up or existing company and take all our returns in royalties in exchange for the IP. We weren’t an investor,” Shenk says.

The old model had allowed UniServices to build a strong balance sheet before it began to take a bigger investment role, using $10 million of what it had earned to that point to form the inventors’ fund.

Within the year, the fund had doubled to $20m, and last year, it doubled again.

“Our expectation and aspiration is that this continues to grow. We’re aiming to say yes to good ideas as often as we can,” Shenk says.

Although most of the estimated $2.1 billion worth of the medtech sector is in one company – Fisher & Paykel Healthcare – the impact of university spinouts is growing.

Shenk says UniServices has invested roughly $13m of capital in 19 medtech spinouts and currently values its holdings in those companies at $48m.

He doesn’t want to comment on which are the best performers.

“We love all our children and lots of them have made amazing technical and regulatory progress. Alimetry is a terrific example of that but we’ve had several failures, too, including of things that were going gangbusters.

"If you have no failures, I believe you’re not trying hard enough, you’re not reaching far enough into the realms of possibility,” Shenk says.

At present, about 70% of its portfolio by value is in medtech companies.

Shenk says while UniServices regards itself as a reasonably long-term investor, it doesn’t believe it’s appropriate for the company to hold shares in publicly-listed companies.

One of the first recruits to Alimetry’s growing workforce – it now numbers 35 – was former Fisher & Paykel Healthcare clinical business lead Hanie Yee, who was employee number five when she joined as chief operating officer in mid-2020.

'There is always risk'

Yee describes medtech as something of a new kid on the block for NZ investors who are more used to pharmaceuticals and software.

“The medtech playbook is very new. It’s still written in pencil and it’s a draft,” Yee says.

Moving from F&P to a startup was, she says, like jumping from an oil tanker to a jetski.

“Life in a corporate is safe and I had very high job security – on an oil tanker you will always get to your destination. But it’s a lot less exciting and sometimes it’s hard to know just what your contribution is among everyone else’s.

"I look at startups, and Alimetry when I first joined … they are agile, you can turn the handle and it goes every which way, you have the time of your life, however, there is always the risk you are going to run out of fuel and get stranded in the middle of the ocean."

That seems unlikely any time soon, with Alimetry attracting more than $16m in a capital raising last year from the likes of international tech investor IP Group – now its biggest shareholder – and local firms Movac, Sir Stephen Tindall’s K1W1, science and deep-tech investors Matū Group and UniServices.

Matū Group’s Dr Andrew Chen, who runs the fund’s due diligence processes and is chair of the Return on Science Digital Technologies Investment Committee, says Alimetry is currently “the gold star” of the NZ medtech scene and it’s having a big influence on other startups.

He says it’s Matū’s best-performing investment and its FDA tick was a “massive” boost.

“If someone is telling me they can sell it in NZ, that doesn’t really give me that much confidence – I still want to see them go through the FDA process. Before that point, everyone is investing on the promise that this product can go into the market," Chen says. "If they’d failed the FDA process the company shuts down because they can’t sell the product.”

A trailblazer

Matū’s investment portfolio of 17 companies includes four medtechs and five University of Auckland spinouts.

Chen says Alimetry is a trailblazer for other companies in a sector that is not sufficiently celebrated because many innovative devices simply disappear into the medical supply chain. “You might not encounter it as an individual until you need that product and even then the clinician is the one using it and you might not even know what it’s called. The doctor is not going to tell you that this is a NZ test in the same way we’d champion NZ beef you’re buying on the supermarket shelves.”

He says NZ punches above its weight in the field, partly as the result of the impact of Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, but also through an aggregation of effort into institutions such as the ABI.

“But when you look at all the sectors of science and technology commercialisation, medtech is one of our strengths that not enough people know about,” Chen says.

Yee, who heads the Medtech and Surgery committee of science research advisers Return on Science, says the biggest mistake made by the would-be entrepreneurs whose projects they assess is a failure to validate whether the problem they think they’ve found a solution to is actually a real one.

Yee, who heads the Medtech and Surgery committee of science research advisers Return on Science, says the biggest mistake made by the would-be entrepreneurs whose projects they assess is a failure to validate whether the problem they think they’ve found a solution to is actually a real one.

“Most of the people who come to my committee are very enthusiastic scientists, but just because it’s a cool science project doesn’t mean that in the real world of commerce anyone is a) going to pay for it or b) that the problem is as big in the real world as academia," Yee says.

“They get hyper-focused on something, really go deep and spend a tonne of money and resource to solve it without asking how often this applies.”

That’s not a problem for Alimetry – O’Grady says 10% of people suffer gastric dysfunction with symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and indigestion.

Far bigger potential

After abandoning a degree in engineering and physics at Canterbury, O’Grady, now 44, moved to Auckland where he obtained his medical degree.

He then trained in surgery before doing a PhD through the ABI where the institute's head, Professor Peter Hunter, recognised his rare talent for entrepreneurship.

Hunter says only about 1-5% of PhDs or post-graduates have that ability.

Other stars in the category include Professor Simon Malpas and Dr Daniel McCormick, the brains behind another startup, Kitea Health.

Malpas, a professor of bioengineering and physiology at Auckland University, and McCormick, a senior research fellow at the institute, have developed a tiny device that can be inserted into the brain to measure pressure in the skull in patients with hydrocephalus.

But its potential is far bigger if it can also be used to measure pulmonary artery pressure in patients with heart failure.

Although the research and entrepreneurship fostered at the ABI have put Auckland and the University of Auckland at the forefront of medical device and digital health development, the institute has also helped to found and nurture a national network linking the four main centres through the Consortium for Medical Device Technologies.

In 2012, Hunter and the ABI’s strategic partnership lead, Dr Diana Siew, began the consortium – a partnership of the Universities of Auckland, Otago, Canterbury, the Auckland University of Technology, Victoria University of Wellington, Callaghan Innovation and three Te Whatu Ora innovation arms at Auckland, Waitematā and Capital and Coast Health, aiming to connect research and industry nationally and internationally and foster collaboration between the institutions.

The next stage of this development is Medtech IQ Aotearoa – a national innovation hub linked to four regional hubs in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin.

Siew says it’ll be modelled on places such as Sydney and Melbourne.

“There is a huge innovation hub in the Monash area in Melbourne and another in Westmead and Randwick in Sydney, but you can’t pinpoint that in NZ.”

Alimetry’s Yee says that Medtech IQ could cement NZ’s place in the international medtech scene.

“There will come a day that NZ is not just a beautiful postcard but a hub of talent – the southern hemisphere’s Silicon Valley,” Yee says.