After 40 years running a general practice in West Auckland, Jenny Miller has had enough.

She worries the 67-year-old co-owner of TL Care, Dr Tony Lowe, will die at his desk “because the demand is so huge and there is nobody coming in to replace him”.

Goodwill and loyalty to their patients is what keeps them going, she says.

“These last few years have been relentless. We have worked incredible hours, almost seven days a week. We are unlike any other business where we can just shut up shop and take a break. In fact, we have not had a break for two years.”

TL Care’s very low-cost access practice’s loyal patients are 70% Asian, about 8% Māori, and 7.5% Pasifika. Its roll is unusually high at 5,600 patients for two doctors because it’s one of the few practices in West Auckland with doctors speaking Cantonese and Mandarin.

The consultation fee is capped at $19.50, but many patients do not pay because they cannot afford it, have a disability, are dying or their family has died, Miller says.

The practice regularly waives fees and writes off accounts.

‘Archaic’ model

TL Care started as a traditional GP-owned clinic in the 1960s with its founder doctor living at the back of the premises. It has since expanded and the front offices house the admin team these days, with the surgery nestled at the back.

The two doctors working at this “old-fashioned” GP clinic, which runs more like a rural practice than a typical major city surgery, serve patients in person or on the phone.

Despite increased pressures, patients can still get same-day appointments or walk in and wait a few hours to be seen.

The waiting room is always full. On a Tuesday at 10am, there would be about 20 people waiting to see a doctor or a nurse.

The waiting room is always full. On a Tuesday at 10am, there would be about 20 people waiting to see a doctor or a nurse.

Lowe, who has worked at the clinic for almost 40 years, doesn’t go home until 11pm some nights. The other doctor, who has worked there for 20 years, often works weekends until 8pm.

Between them, they have up to 160 patient contacts a day, including in-person and phone consultations, prescription requests, forms, referrals, hospital and pharmacy calls.

“We pride ourselves that if you are sick, you will be seen. But this comes at a huge personal cost. One of the doctors is totally dedicated to his patients and works incredibly long hours and almost seven days a week,” Miller says.

TL Care still makes house calls. It sends flowers to a patient’s family when they die, and provide assistance, including money, if the family is struggling. Sometimes they attend the funeral.

“We are archaic and, in reality, something from days gone by.”

Traditional model in decline

Miller is one of hundreds of owner-operators of general practices in Aotearoa who are struggling to stay afloat amid pressures including increasing demand and complexity of health needs, staffing shortages and increasing costs.

In the last five years, local and overseas corporations have aggressively bought such owner-operated surgeries, offering administrative relief or a welcome exit to burnt-out doctors and managers.

Primary Health Organisations (PHOs), which are not-for-profit networks distributing public funds to general practices and providing primary health services, have also stepped in to buy practices on the brink of collapse.

At least 50% of GPs plan on retiring in the next decade, according to the College of General Practitioners.With GP ownership being increasingly less attractive to newer generations due to huge workloads and funding issues, this could open the door further for corporations to take over.

Critics warn the decline of the owner-operated model of general practice in favour of GPs becoming salaried employees or contractors is coming at a cost to patients, with shorter consultations, longer wait times and less equitable outcomes in an already unequal system.

Te Whatu Ora does not hold data on the ownership structure of GPs. Most are private businesses who contract their services to the government through a PHO.

There is no definitive database recording who owns our GPs, with changes in ownership happening almost daily at the moment, General Practice Owners Association chief executive Philip Grant says.

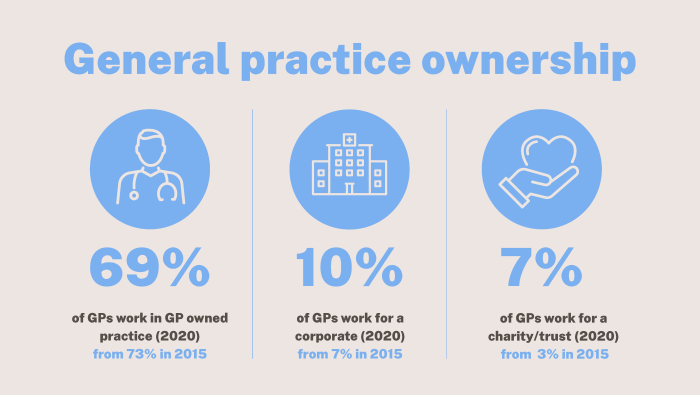

About 69% of GPs work for a practice owned by one or more GPs, according to a 2020 College of GPs workforce survey, down from 73% in 2015.

The proportion of GPs working in fully or partially corporate-owned practice increased from 7% in 2015 to 10% in 2020. Over the same time, the percentage of GPs working in community, trust or charity-owned practices has increased from 3% to 7%.

Rise in corporate ownership

In the last three years, corporations have been gobbling up medical centres like they're lollies.

More than 40 medical centres went fully or partially into a network in the 18 months to October, about three times the number of transitions that went through in 2020, NZ Doctor reported.

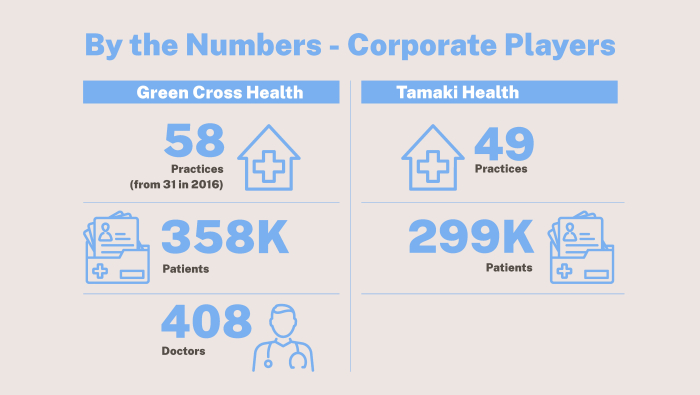

Green Cross Health, this country’s biggest corporate player in the GP sector, owns or partially owns 58 general practices serving 358,000 patients across the motu.

It employs about 1,200 people in its medical division, including 408 doctors. The listed company has been growing its network from 31 medical centres in 2016 to 58 in 2022, and plans to “continue growing rapidly”, medical general manager Wayne Woolrich says.

Green Cross Health offers preferential pricing and agreements for essentials including medical consumables, IT, management systems, banking, insurance, union bargaining, refit property and signage contractors, group funding arrangements and networking.

It offers leadership and operational support, corporate governance, clinical support, performance optimisation, financial management, payroll, property, recruitment, human resources, branding and communications and IT.  Green Cross medical general manager Wayne Woolrich says the listed company plans to keep growing. (Image: Green Cross)

Green Cross medical general manager Wayne Woolrich says the listed company plans to keep growing. (Image: Green Cross)

Woolrich says: "Running a practice in today’s climate with significantly increasing admin, the changes that covid-19 has brought, workforce shortages and burnout, makes partnering with a corporate like Green Cross Health very attractive.”

Values and trust are key to make a partnership work, and Green Cross doesn’t “come in and change everything”, he says.

Corporate ownership “is all about investment back into the practice” to benefit staff and patients, he says.

Tāmaki Health, which is almost fully owned by Australian-based Mercury Capital, has ownership in 49 practices and urgent care clinics from Whangarei to Christchurch, serving about 299,000 enrolled patients. More than half of Tāmaki’s clinics are very low-cost access practices serving very high-needs populations.

Christchurch GP Angus Chambers last year brought in corporate Tāmaki Health to his Riccarton clinic and urgent care practice. Tāmaki is now a shareholder in the company, along with five GP owners.

For Chambers, this is part of his exit strategy. Tāmaki Health also lightens the practice’s load by taking over HR and recruitment functions.

“You can do these things, but it is extraordinarily expensive,” he says.

‘Concerning’ trend

For Victoria University public policy senior lecturer Verna Smith, the rise in corporate ownership is a concerning trend.

She says the arrival of big corporations is going to increase cost barriers for Kiwis who already struggle to afford a doctor’s visit.

The government needs to “think very hard” whether it wants to let the primary care sector get more and more privatised, corporatised and expensive, she says.

“The US system is the worst in the world because corporate interests dominate.”

College of GPs chair Bryan Betty says running a clinic is becoming increasingly difficult. (Image: Supplied)

College of GPs chair Bryan Betty says running a clinic is becoming increasingly difficult. (Image: Supplied)When GPs have skin in the game, they work longer hours and it benefits patients, college of GPs chair Bryan Betty says.

He believes it is still a good option for GPs to own a practice, but increasing workloads and underfunding is pushing many to exit and sell out.

“If it wasn't for some of those corporations, significantly more of our community would be left without essential services,” GenPro chief executive Philip Grant says.

Corporations are increasingly investing in essential frontline services in areas that are not necessarily seen as attractive for owner-operator GPs or where they are retiring. But Grant says corporate-owned general practices may have set hours and set annual leave periods, which often go by the wayside for a GP owner-operator when the pressure is on and patients need them.

“The public should be concerned if underfunding means those businesses are no longer sustainable for the GP owner-operators and even more so if it is not viable for corporations to consider stepping in.”

Te Whatu Ora board chair Rob Campbell says concerns about the rise of corporate interests are legitimate, but these groups are filling a gap in the sector.

"My own personal view is that I would much rather that we had a very strong public sector that was meeting expectations so that there was not a need for private corporate investment in the sector.

The reality is that the government has not been willing to fund to the full expectation of most of everyone and therefore that does create opportunities for corporate investment to grow," he says.

But the old model of the owner-operator GP was changing and corporate structures could increase the level of service.

"If corporate structures are more efficient, if they provide a more equitable service and meet our overall objectives then we have no reasons to be concerned about corporate ownership of general practice ... But given the amount of funding they are given from the government we will be insisting that we have really good info from them about their economics and we will be insisting that they meet our standards of care and equity." Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell says the rise in corporate ownership is neither good nor bad; it's just a sign on a changing model. (Image: NZ Herald)

Te Whatu Ora chair Rob Campbell says the rise in corporate ownership is neither good nor bad; it's just a sign on a changing model. (Image: NZ Herald)

PHO’s evolving role

As PHO’s future under the health reforms has come under threat – it is unclear whether their contract with the government will continue past June 2024 – it appears some bigger networks are looking to grow their commercial arm to ensure revenue beyond public funding in the future.

PHOs traditionally bought a handful of GP clinics as a last resort when communities were at risk of losing their only family doctor. Because the networks manage funds and support general practices affiliated with them, this could lead to conflicts of interest.

Procare, a cooperative network of 167 GP clinics serving 788,190 enrolled patients in Tāmaki Makaurau and Te Tai Tokerau, this year purchased Health New Lynn to the tune of $15 million through its Elevate programme. The Procare group took on a $2.8m loan and a $6.5m flexible credit facility with ANZ Bank to enable acquisitions, according to its 2022 annual report.

BusinessDesk understands others, including corporations, were interested in the purchase. It was not a last resort situation.

Elevate, which owns five practices, “is transforming practice ownership to make it more accessible, rewarding and sustainable for the next generation of clinician owners” through flexible buy-in options, a supportive collegial environment, and ongoing service provision, quality improvement and innovation opportunities, Procare says.

When Elevate launched, Procare said the intention was to purchase clinics for an interim period to ultimately introduce new clinical owners.

“We know how hard practice ownership can be, particularly in uncertain times, but we’ve also heard repeatedly within the cooperative that GPs and nurses want to preserve that independent clinician business model rather than opt for corporate ownership. We’re in an ideal position to play an active role in this,” a 2020 press release said. So far, the clinics it has purchased have not transitioned back into the community.

Procare chief executive Bindi Norwell says there are scaffolds in place to ensure there is no conflict of interests when a PHO buys a general practice. (Image: Supplied)

Procare chief executive Bindi Norwell says there are scaffolds in place to ensure there is no conflict of interests when a PHO buys a general practice. (Image: Supplied)Procare chief executive Bindi Norwell says Health New Lynn was a fantastic integrated practice with a range of health professionals, which would provide a “massive training opportunity”.

Elevate is a business separate from the cooperative, with separate governance and scaffolds in place to ensure there is no conflict of interest. It sits alongside a brokerage service, which helps clinicians get into practice ownership.

Fees under the spotlight

Clearly, owning a clinic is becoming increasingly difficult and unattractive for clinicians. The health reforms are a great opportunity to review this ownership model, Smith says.

She, and other academics, would like GPs to become free for all to remove cost barriers to care and form a more equitable health system.

This could be done through government funding covering all costs of running a general practice, with GPs continuing to run their practice privately, as is done in the UK, a recent

Association of Salaried Medical Specialists report found.

A “more radical option” would have the government put all GPs on a salary and gradually buy clinics, the report says. Either option would cost billions of dollars.

Aside from the cost, another obstacle to achieving a free primary healthcare system could be GPs themselves, given their historical objections to becoming ‘salaried employees of the state’, the report said.

“GPs in 1938 were nervous that, if fee-charging were banned, state payments would not keep up with the true cost of delivering healthcare (or the income they wished to enjoy).

“To some extent that fear has been borne out, as the proportion of a visit cost covered by the public subsidy has diminished over time.”

For the report, researchers interviewed several GPs and found they had mixed views on the question.

“Undoubtedly, many would remain resistant to being brought more fully into the public healthcare system, seeing themselves as independent businesspeople who value the freedom to charge as they see fit,” the report said.

But attitudes are changing among the new generations of GPs, who are increasingly wanting to work part-time and have a better work-life balance, the report said.

Regardless, making GP visits free beyond the age limits that are already funded is not on the government's agenda, former health minister Andrew Little told BusinessDesk before it was announced Dr Ayesha Verrall would replace him.

“It would cost considerably more to do so. There will always be limits on government spending.”