The grass is rank, the driveway a mud-caked jumble of debris, and the house on a hillside at Muriwai that Abe Dew and Maria Koppens have called home since 2006 lies empty.

Just metres away – an important eight metres, to be precise – from one side of the house, the ravages of Cyclone Gabrielle have torn down what was once a bush-clad hillside, leaving a gaping scar.

At the bottom of this scree, one of several massive landslips on the escarpment above one of west Auckland’s most popular surf beaches, lie the remains of former neighbours’ homes.

From the ruins of one, a crushed car sits where it was parked in what was once the garage.

At this site, two local volunteer firefighters, Dave van Zwanenberg and Craig Stevens, lost their lives on that fateful night of Feb 13, almost three months ago to the day this week – a week in which another “atmospheric river” hit Auckland, triggering a local state of emergency.

Clare Bradley, owner of the red-stickered Muriwai Lodge across the road from this scene of destruction remembers how the “terrifying wind” from the cyclone suddenly “whipped around” mid-afternoon to batter the settlement from the southwest that afternoon.

The new wind angle seemed to be the last straw for the waterlogged hillsides and the first major slip was at about 11pm. Others followed.

By dawn, not only was Muriwai no longer the place it had been just a day before, it had suddenly become a case study in one of the knottiest problems of managed retreat.

Insured, but not insured

The issue is this: not only are more than 100 homes in Muriwai red-stickered, meaning residents cannot return to them, but more than 85% of those homes are undamaged.

Instead, the land on which they sit has been deemed at “imminent risk” of further slips.

As a result, home insurance policies won’t “respond”, as they say in the insurance industry.

Imminent risk is not judged to be an insurable loss, on top of which, most home insurance policies don’t cover landslides, except to the extent that the Earthquake Commission (EQC) covers damage to the land itself.

Who knew?

The wording on the Dew/Koppens policy explicitly details that they are not covered for “subsidence, erosion and landslip”.

Meanwhile, the EQC compensation is complex.

It offers a payout for damage to land within an eight-metre boundary of a dwelling. Luckily – if that’s the word – for Abe Dew, this eight-metre designation includes the clothesline, which now sits a precarious 2.5 metres from the edge of the landslip that has carried away parts of the family’s section.

Oddly, this vital bit of household infrastructure, along with any sheds, can be counted as the boundary for EQC’s purposes, while septic and rainwater tanks don’t.

The view from the clothesline. (Image: Maria Koppens)

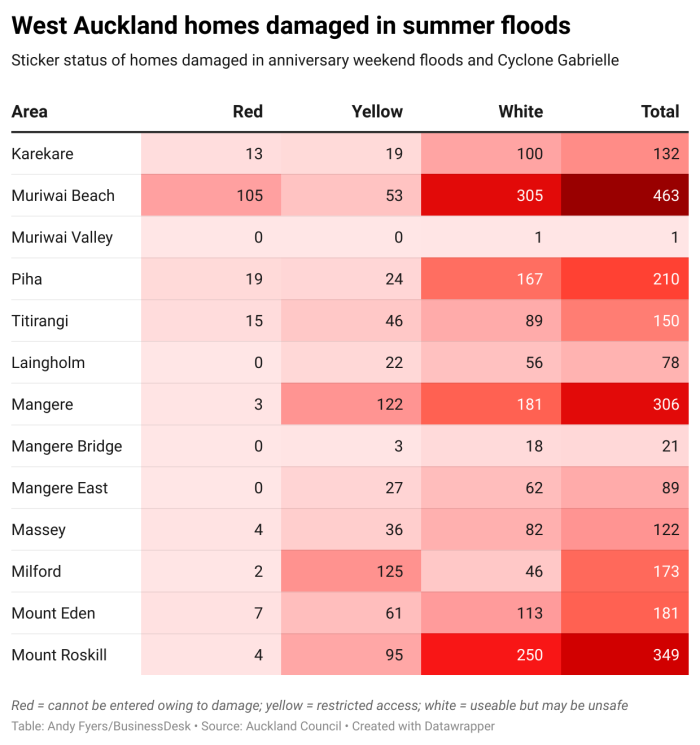

In total around New Zealand, but mainly in Auckland and its west coast beach communities, there are perhaps 400 homeowners in this situation: with undamaged homes that they cannot return to.

They are in a totally different situation from the 10,000-plus homes damaged by flooding in the early new year extreme weather, where insurance policies will pay for repairs.

They are also a vanishingly small problem, in dollar terms, compared to total damage from Cyclone Gabrielle and the Auckland anniversary weekend floods that the government has estimated at between $9 billion and $14b.

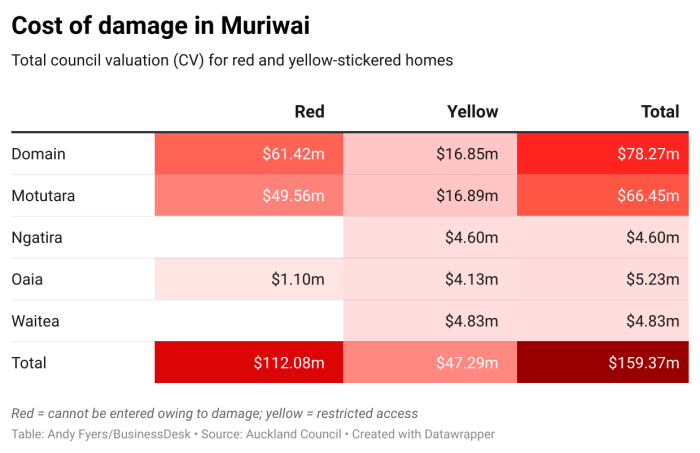

Muriwai property owners’ $100 million-plus problem – assuming perhaps 100 one-million dollar homes are permanently red-stickered – might seem to pale into insignificance.

However, the insurance loophole they’re caught in is one that can be expected to arise more and more frequently as extreme weather linked to climate change visits more regular destruction that prevents homeowners from ever returning, or houses ever being built again.

That means the Muriwai and other landslip-affected homeowners require decisions by central and local government, as well as by insurance companies and banks that have covered or lent on such homes, which will likely set precedents for decades to come and potentially affect thousands more such uninsured properties.

“We are not in the flood-damaged pool,” said Koppens, pointing out that of the 400 homes red-stickered after Cyclone Gabrielle, “more than a quarter are in Auckland, Muriwai, Piha, Bethells, Karekare”.

“The 10,000 flood-damaged homes will receive a payout (from their insurers). We won’t receive a payout because our homes aren’t damaged.”

In theory, homeowners left in this situation could face financial ruin – compensated for just a fraction of the value of their properties while remaining the owners of undamaged, but uninhabitable homes.

In practice, a behind-the-scenes scramble is going on to find a solution to prevent that happening.

After years of theoretical discussions about who will pay for “managed retreat” from places rendered uninhabitable by extreme weather, Muriwai has become the epicentre of an issue at the sharp end of climate change adaptation.

For now, however, the primary actors in any solution – central or local government, insurance companies or banks – are engaged in a complex game of chicken.

All know that they will have to bear some of the cost of whatever the solution is, but no one wants to blink first.

For the Insurance Council of NZ, the issue is so sensitive that for weeks it has been unwilling even to background brief on the issue.

It’s why Auckland’s mayor, Wayne Brown, has made it clear that “our current position is that Auckland council is not a guarantor of private property interests, and we are generally not responsible for compensating property owners in case of loss due to a severe weather event or natural disaster”. The eventual answer for such residents is “part of a complex national response”.

“We are an extremely vulnerable group,” said material produced by Restore Muriwai, a coalition of residents whose collective resources are bolstered by the fact that many come from high-powered white-collar backgrounds in law, advertising, communications, and other upper echelons of corporate life.

While their insurance policies may not cover them, they are pooling their collective skills to ensure that they are heard.

This has both pluses and minuses.

On one hand, they can appear to be a privileged group. They were told in one meeting that while their issues were acknowledged to be acute, so were those of people in low-income Massey, who were ripping flood-damaged carpets out of their homes.

On the other, their advocacy may help speed the development of a template for the future approach to compensation for managed retreat.

As many as a third of the worst-affected homeowners are “open to a government buyout”.

“Muriwai is the squeaky wheel,” said Dew.

"We are pragmatic. We understand how the system works. We’re not looking for unicorns presenting cheques, but one of our concerns is that no one wants to be left holding the baby.”

Budget relief?

The reality is that although central government doesn’t want to take full responsibility for the “moral hazard” costs of managed retreat, nothing will happen until it gives direction.

“We’re just waiting to hear what Grant says,” said one insurance industry source, referring to the finance minister, Grant Robertson.

That guidance may start to emerge this weekend when Robertson and the cyclone recovery minister, Kieran MacAnulty, make pre-budget cyclone relief announcements.

Tellingly, those announcements will be made in Hawke’s Bay, where most of the impacts are flood damage, and may include decisions on how to retreat from repeatedly inundated areas such as the Esk Valley. Whether any new policy will also cover the landslip-affected minority remains to be seen.

In the meantime, geotechnical work is under way to assess which or whether the worst affected parts of Muriwai can ever be repopulated.

“We expect the road to be safely opened, but whether it’s safe to live and work there may be a different question,” said Clare Bradley, whose Muriwai Lodge is on Motutara Road, which is now being cleared, and whose beautiful home with coastal views on Domain Road is yellow-stickered.

Three months on from the cyclone, there are still checkpoints at roadblocks on the main entrances to Muriwai and access to the beach remains restricted.

Residents place blue placards on their dashboards to signify their status to the security guards who control access to this usually popular area.

“Muriwai gets a million visitors a year from Auckland,” said Dew.

“I wonder how they’re going to manage that in future if there’s a Hurricane Katrina-style wasteland of derelict homes here.”

One small glimmer of hope is the lessons learnt in the Port Hills of Christchurch, where the risk of post-earthquake rockfalls also placed undamaged homes at risk more than a decade ago.

“A similar assessment after the Christchurch earthquakes in the Port Hills took several years, but we’re using the experience from the Port Hills – the lessons from that – to help us reduce the time that this assessment has taken down to six months,” Auckland council’s principal geotechnical expert Ross Roberts told Muriwai residents in an update last week.

That should mean decisions on even the worst affected areas by the end of August, he said, adding the important caveat: “as long as everything goes to plan”.

In the meantime, Dew talks about “clusters of distress” in the community, particularly for those caught in what he calls the “equity trap” of having to pay mortgages on homes they can’t live in, rent on temporary accommodation, rates on their properties and a looming uncertainty for anyone whose insurance policy needs to be renewed before resolutions are finalised.

“No one knows how this works,” he said, in part because there are so many unanswered questions.

“We want the insurance companies to front-foot and extend periods of temporary accommodation allowances – some have 25 weeks, some 12 months,” said Koppens.

Bradley praises her insurance company’s approach to the business interruption policy on her lodge operation.

Opened in December 2021, in the midst of the covid disruptions, the insurer has acknowledged that by the time of the cyclone, the business was undergoing a post-covid growth spurt that it’s taken into account in calculating her compensation for lost business.

But the waiting and the worry are taking their toll.

“It’s the anxiety, what keeps you awake at 3am,” she said.

“And the grief,” Maria Koppens adds.

A graphic in this article has been updated to make clear that the information relates primarily to West Auckland homes, not the whole of Auckland.