Wellington art auction house Dunbar Sloane marked the end of an era this week, bringing the hammer down - or in this case, an HB pencil clasped in the left hand of veteran auctioneer Anthony Gallagher - on a stylised bronze coin by New Zealand sculptor Terry Stringer titled, fittingly for a time of pandemic: "This Era".

That sale completed not only the first fine art auction in Wellington of the post-covid era, but the last fine art auction ever to be held at the 101 year-old business's premises on the corner of Maginnity and Waring Taylor Streets. The next one will be in spanking new quarters nearby.

After a marathon three sessions auctioning nearly 500 items to bidders in the room, on the phone and - for the first time - online, Gallagher described market sentiment as "beyond buoyant."

"There's money out there," he says, although it takes longer to extract now. Gallagher says online bidding slows the dynamics of open outcry auctioneering, that ancient "social process of establishing value."

“We generally do really well in recessions, but the market is particularly strong," Helena Walker, director of fine and applied art at Dunbar Sloane, told BusinessDesk. "People at the top end of the market still have money."

A week earlier, a big selection of gold coins had fetched far higher prices than the estimates - $700-to-$800 instead of $350-to-$550 - reflecting more than just the rising price of precious metals in uncertain times.

Auckland buzzing

In Auckland, just a couple of weeks earlier, the results of the first major fine art auctions since pandemic restrictions started to ease had also demonstrated an apparently enduring truth: that art is at least partially recession-proof.

Faced with the lowest interest rates on bank deposits in history, closed borders killing winter holidays in warmer climes, and four weeks cooped up staring at the walls at home, people with money in the bank appeared quite willing to spend that money on beautiful things.

"One of the fundamentals of the art market is that it involves real money," says Auckland-based writer and arts adviser, Hamish Coney, who until recently was a director of one of the city's top galleries, Art + Object. "Generally, people don't borrow money to buy art like they would for a house or a car."

The lockdown's delay to the usual annual schedule of art auctions may also have helped.

"There is always pent-up demand for the April auctions," says Coney. This year, that demand remained pent-up until May and early June, thanks to covid-19.

What a relief!

Nonetheless, the success of these first major sales of 2020 is also an enormous relief for the art auction houses.

The last big auctions were held before Christmas last year. Art dealers always spend the lean summer months trying to fill their autumn auction catalogues with rare and valuable surprises to generate demand.

"There are only 10 or 12 pay days a year," says Coney. "Every other day, you are spending money" - on staff, on premises, and on publishing the glossy catalogues that are an essential part of the magic of art auctions.

Freely distributed to any potential bidder, catalogues commonly cost around $40,000 to produce, says Coney. An annual production cost for catalogues alone of $300,000 to $400,00 is unavoidable for a serious gallery.

So, imagine publishing catalogues in February for auctions to be held in April, replete with carefully calibrated estimates for the value of each work to be auctioned, only to have the events cancelled or postponed by a global pandemic that just might throw those valuations all to hell anyway.

That made the recent auctions a bit of a white knuckle ride.

"We were first cab off the rank," says Richard Thomson, at Auckland's International Art Centre, whose April 1 auction was postponed to May 19. "It was a bit of an unknown."

Thomson had debated holding an online auction during the full lockdown period to keep cash flowing, but baulked at selling high value works without physical viewings.

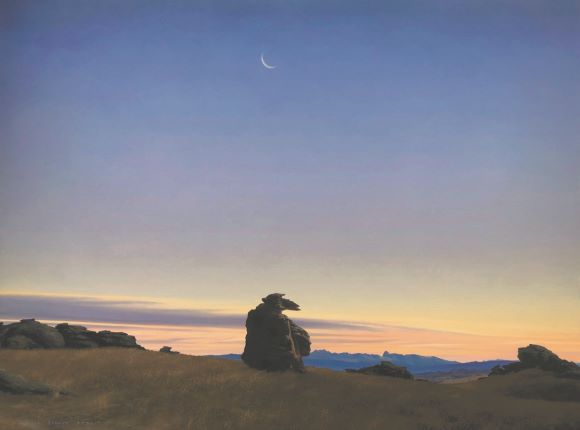

Grahame Sydney, Rock of Ages, fetched $140,000 on May 19 Instead, they put some work up online, hoping to sell maybe five out of 50 works on offer.

Grahame Sydney, Rock of Ages, fetched $140,000 on May 19 Instead, they put some work up online, hoping to sell maybe five out of 50 works on offer.It was a huge success, with minor works by Colin McCahon and Grahame Sydney fetching a respectable $27,000 and $35,000 apiece, and about half the catalogue selling.

"I had thought that buyers and sellers would both be a bit cautious."

That set the tone for May 19's first physical auction of the year.

Again, there was "solid" demand.

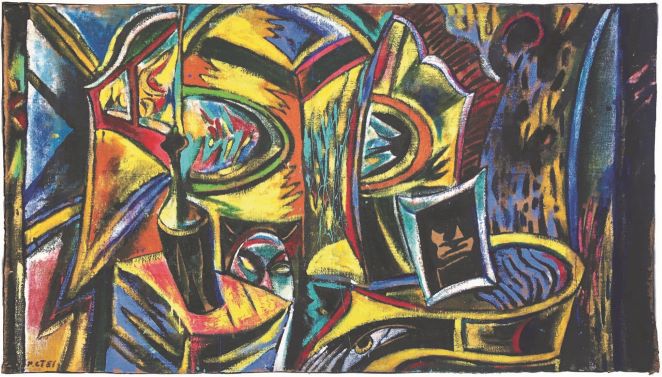

A large work by painter Philip Clairmont fetched $150,000, the top end of the $100,000-to-$150,000 range placed on the work and "the second-highest estimate in history for that artist," said Thomson.

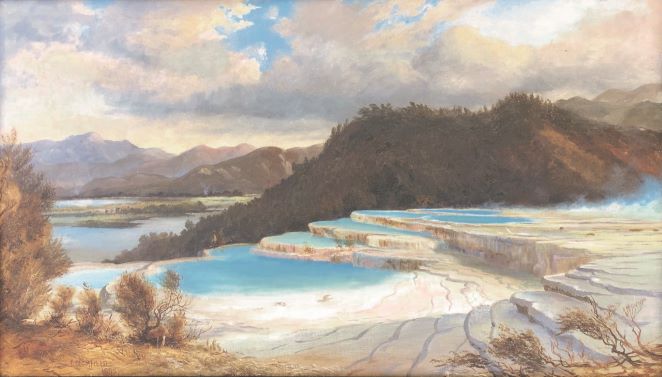

He watched amazed as a pair of paintings of Rotorua's Pink and White Terraces by 19th century artist Charles Blomfield fetched $112,000, more than twice the bottom end of the $40,000-to-$60,000 valuation range.

A Blomfield pair sold at auction for $112,000

A Blomfield pair sold at auction for $112,000Numerous other works have fetched solid prices in negotiated sales in the fortnight since that auction.

A buzz started to get around the art world.

"I feel there's been a slight improvement in the market," says Thomson. "Maybe a five-to-10 percent lift. I think it's exciting times."

He's got a major work by Charles Goldie already lined up for the centre's next fine art auction, in August, valued at around $400,000.

"I'm thinking we're on the verge of growth and understaffed and we have work on our hands. I can sense it."

Gauging sentiment

However, Ben Plumbly at Auckland's Art + Object gallery sounds a note of caution.

He also had to delay the first fine art auction of the year and was two days behind the International Art Centre when it put its 'Important Paintings and Contemporary Art' selection under the hammer on May 21.

Sales on the night were $1.67 million and rose to $1.86 million in following days with negotiated post-sale offers.

"This represents a phenomenal result for the New Zealand art market in the immediate aftermath of the covid-19 lockdown and the resultant delay from our original auction date of April 1," the gallery says on its website.

A McCahon print, 'Moby Dick is sighted off Muriwai' fetched $21,022, way above its estimated range of $8000-to-$14,000, while a Paul Dibble work, 'Green Tango', went for $102,106, against an expected range of $65,000-to-$85,000.

But Plumbly reveals how much work was involved behind the scenes to ensure the auction would succeed.

"Auction houses generally have periods of very little revenue through December, January and February," he said. "Our costs continue but it's hard to sell high value works. We came out of that and put all our effort and expense into an April 2 auction that we then weren't able to hold. It was a very difficult time for us financially."

Sensing a bargain, some buyers sounded out the possibility of 'buy now' offers, or direct negotiations with the paintings' owners. Plumbly thought hard about whether to do an online-only auction.

"But we felt it was a very strong catalogue. We decided to do none of those things."

Instead, he got on the phone to the dozens of vendors with works in the auction "to ask whether they would give some leeway on their reserve prices."

"Most gave me 10 percent discretion. That proved to be quite key."

Top end of the market

It was particularly important at the very top end of the market, where there are inevitably fewer buyers and serious collectors can push harder for sharp prices when economic times are tough.

Plumbly cites a "magnificent" Don Binney work that had been with the same private collection since 1963.

"It was exceedingly well provenanced. We estimated it at $400,000 to $500,000, in line with major sales in the last couple of years."

Playing it safe, he negotiated with the owners to bring their reserve price down to $350,000 "and it sold for that under the hammer."

"It was easily the most expensive painting to sell on the night. In another market, I'm confident would have reached that initial estimate, but that discussion proved key.

"There were a lot of works that sold above estimate, but that at the upper end, works were selling for around their bottom estimates. I hope that gives you an honest inkling of the type of work that goes into making a sale successful," he said.

And there is no avoiding the fact that the Auckland Art Fair, a major annual event at which as much as $10 million of sales occur to a range of local and international buyers, simply could not occur this year. While its organisers have innovated to replace the physical event this year, nothing replaces the dynamics of an exhibition involving dozens of artists and thousands of potential buyers mingling amongst the works themselves.

Coney describes the art market in this country as "small, resilient: New Zealanders buying New Zealand art. It's not speculative. It's even slightly boring."

With total annual turnover of between $20 million and $30 million, he's not too surprised that there was pent-up demand on display for the first big auctions of 2020.

More telling, he thinks, is the sense of optimism he's been getting from conversations with the primary market 'dealer galleries' where new, original work is sold.

"One of the things I'm getting, talking to dealers, is that this covid period has been quite positive for them in that they felt some aroha, some manaakitanga, some whanaungatanga as collectors have stepped up to support them.

"Collectors understand that the dealers are a really super-important part of the market and that recognition has buoyed spirits to my mind."