Here’s a prediction: the political commentariat and the government's core support base will sweep aside the $12 billion of additional capital spending announced by Finance Minister Grant Robertson today as unduly conservative – even miserly.

Having raised expectations the government could push out the ratio of net Crown debt to 25 percent of gross domestic product from the current 20 percent limit, the forecasts unveiled in today’s Budget Policy Statement look tame.

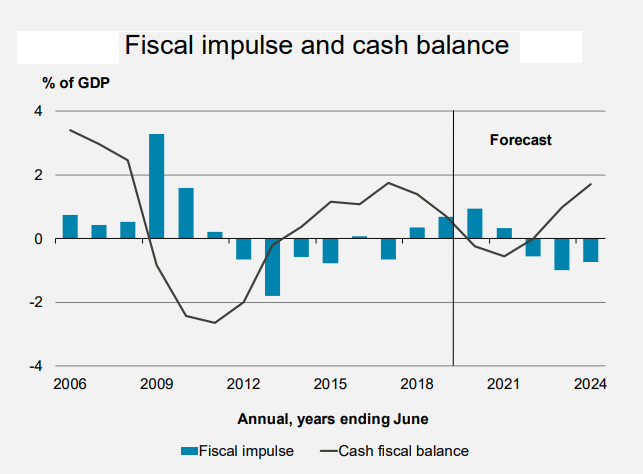

Net Crown debt peaks on the current forecasts at 21.5 percent of GDP in 2022 before falling back to below 20 percent of GDP by 2024.

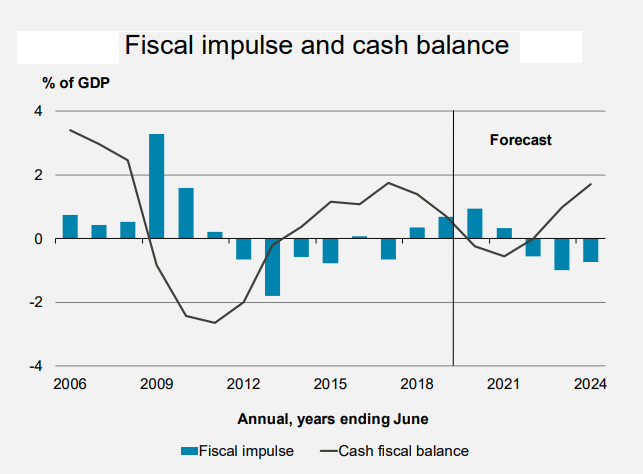

More to the point, the overall impact of the government’s contribution to the economy is contractionary for the last three of the five years in the latest forecast period, according to the Treasury’s calculation of the so-called ‘fiscal impulse’ created by Budget announcements.

In other words, the extra capital spending is a boost to economic activity in the first two of the five years in the forecast period, but the additional capital spending is outweighed by the return to Budget surpluses that occurs from 2022 onwards.

At the heart of this apparent contradiction is the economic indigestion that means New Zealand can only grow at around 2.5 percent a year, in spite of having one of the strongest sets of government accounts in the developed world.

On paper, it could decide to spend far more.

But like trying to stuff a marshmallow in a piggy-bank, the economy’s capacity to absorb more capital projects is limited.

New Zealand remains caught in an odd bind of high population growth, low productivity performance, a very tight labour market and deep shortcomings in the corporate capacity required to deliver large-scale infrastructure projects.

However, today’s capital spending announcements are not the last word on the fiscal outlook that will emerge from the election year Budget.

They serve to give a febrile business community something to feel good about and should go some way to answering the complaint that there has been too much stop-start in infrastructure spending under this government.

And as Robertson noted, capital spending is also preferable to new benefit or tax changes, since any such change in operational spending has an impact on the government accounts forever, whereas capital projects are one-offs.

However, there is still plenty of room to move on benefit levels and, perhaps, income tax thresholds to reduce the increasing problem of fiscal drag on middle income earners who are facing the top personal tax rate on an increasing proportion of their earnings.

On that basis, it is almost inconceivable that the government doesn’t have an election year hip pocket splurge of some sort up its sleeve for the ordinary New Zealand family, which will still leave it comfortably within its new, slightly relaxed debt parameters.